Under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), Aaron Swartz was charged with 13 felony counts for essentially attempting to download a massive database of academic research from the computer servers of MIT, an offense for which he might have served up to 35 years in prison and paid up to one million dollars in fines, were it not for his startling suicide at age twenty-six, in January of 2013.

The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz, the documentary written and directed by Brian Knappenberger, skillfully narrates the intricacies of this complex story with clarity and heart. One cannot leave the theatre without an awareness of the tragic loss of this life cut short and the imperative for legal and judicial reform. The story highlights critical challenges unique to this moment in history. It is a tale that cautions us, if we remain tone deaf about technology and its relationship to our civil liberties, we do so at our peril.

Participant Media is releasing The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz in theatres and On Demand starting June 27. The documentary debuted at Sundance this past January, and I was struck at the time, how both this film and the opening night film Dinosaur 13, portray an Obama administration Department of Justice out of touch, mercilessly targeting individuals for prosecution of “property theft.” In the wake of the financial crisis, where the financial giants escape unscathed, the focus of the Department of Justice prosecutors seems not only misguided, but almost amoral. Participant media has planned strategic social action campaigns in conjunction with the release of the film targeting such prosecutorial overreach by the Department of Justice and aiming to specifically reform the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which has not been amended since it was enacted back in 1986.

I spoke at length with the tech-savvy and impassioned film director, Brian Knappenberger during his recent visit to San Francisco. I questioned him about the nature of Aaron Swartz’s relationship to Lawrence Lessig, and Knappenberger confessed that he always considered Lessig a mentor to Swartz, but learned that Lessig actually credits the prescient and precocious Swartz for inspiring a new direction, examining money in politics, in his own work. As we mourn his devastating loss, Aaron Swartz from beyond the grave forces us to consider, “If you had magical powers, would you use it for good or to make tons of cash?”

Sundance Film Festival 2014, US Documentary Competition. Photo courtesy of Sundance Institute.

Sophia Stein: You started working on this film project a week after Aaron Swartz died. Did you start the project on account of his death?

Brian Knappenberger: My previous film is called We Are Legion, The Story of the Hacktivists. I was doing a lot of panels on hackers and hacktivism. About a week after Aaron died, I was on a panel in New York with Quinn Norton. Almost everybody at this event knew Aaron Swartz and had a story to tell about him. I started filming right away, just trying to get a sense of it. I had been following Aaron’s story since the time of his arrest. I had never met him, but I was following lots of hackers that had run afoul of the law. Aaron’s story didn’t get a lot of attention until he died. After he died, there was this enormous wave of sympathy, frustration, and anger. That week was the week where it was really beginning to take off. So I was filming trying to understand why so many people responded so intensely to this story — not just the people that knew him, but in so many communities where he was this quasi-celebrity.

Sophia: How did you approach Aaron’s family for consent to make the documentary?

Brian: I had a conversation with Aaron’s dad, a month or so after Aaron died. It was a long conversation, and I was moved by it. A pretty close friend of mine, a producer named Brian Gerber, who made films about climate change, had committed suicide about four months before Aaron’s death. So at the time of Aaron’s suicide, I was kind of still reeling, struggling to understand Brian’s death. I had just become a father myself, so there was something very moving about talking to Aaron’s dad. He had just lost a son. I’d lost a friend. I had a new son. It was at that point that I understood that this was a personal story that I wanted to tell. It was also a story that allowed me as a filmmaker to get into all these other deeper issues that I already cared about.

Sophia: All of us, knowingly or unknowingly, have benefited from Aaron’s work. Can you describe some of his most important accomplishments?

Brian: At a very young age, Aaron was a part of group that created the standards for RSS (Real Simple Syndication). RSS is a way that blogs can update themselves from other blogs or news sources. A podcast, for example, would alert their RSS, and then anybody who is subscribing to that RSS would automatically pull that new podcast into their blog. A group of people were trying to make RSS work, and Aaron was a significant contributor to this working group.

What was remarkable was that the other members of the group didn’t realize that they were dealing with a 13 year old boy. Here’s this guy who is more than holding his own in these discussions, really contributing, very opinionated, a little combative even, and they say, “we really want you to come to these face to face meetings.” And he responds, “I am not sure that my mom is going to let me. I’m only thirteen.” Of course, their reaction was, “Wow!” But as Cory Doctorow describes in the film, “Then we all really wanted to meet him!” So Aaron’s mom starts taking him to these conferences, where he starts contributing to these broader discussions about the free flow of information online.

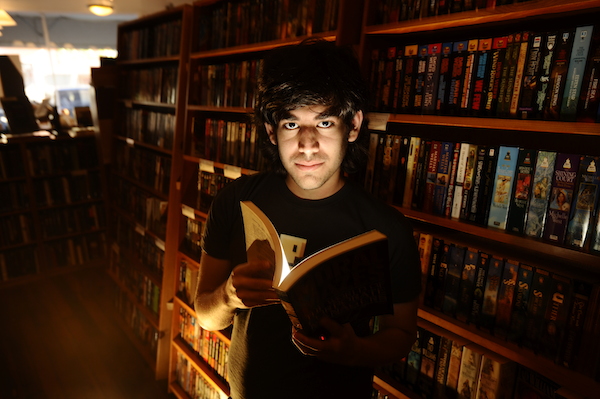

Photo by E E Kim, courtesy of filmbuff + Participant Media.

Aaron was also a technical architect of Creative Commons. Larry Lessig brought him in on the project. Creative Commons provides a set of licenses for artwork created online. You own the copyright, and you can decide to license your work in various ways that make sense for you. You can choose whether or not it is commercial, whether you want people to share it; if they share it, whether and how they must attribute it; whether they can make derivatives. That’s all very lawyerly and non-technical. Aaron found a technical way of attaching that license to a work and having it live with that work.

In a big picture sense, Creative Commons was an attempt to find a path through a split that was happening. On the one side were the content industries – film studios, recording labels — who had concerns about piracy and copyright, but also had this tendency towards zealous prosecution of people who shared content without permission. On the other side was this really chaotic world of piracy, in which there was no respect for artists’ rights, in which there was no way for artists to make any money off of their work. So Creative Commons, if imperfect, was a reasonable way of trying to sort through that.

Photo by Dan Gilmore, courtesy of filmbuff + Participant Media.

Sophia: Next Aaron became a co-founder of reddit?

Brian: Aaron created a site called Infogami that was a part of The Founders Program of Y Combinator series, and he merged with Steve Huffman and Alexis Ohanian to start reddit. Aaron reprogrammed it using a different language, and it really kind of took off. Reddit is the most popular social news site online. Various communities post things, and there is a system of up or down voting allows the best stories to rise the top. Reddit lives on the edge of chaos. It’s everything from Barak Obama doing an “Ask Me Anything” bit, all the way down to “revenge porn” and other awful trolls. There have definitely been some issues with reddit, but it’s an example of a hacker-like platform that emphasizes freedom of speech and expression in its most extreme sense.

Sophia: Many people have been inspired by Aaron’s life and his example as a tech millionaire who put his programming skills in service of social justice and the public good. What do you think inspired Swartz’s generous vision?

Brian: I think he was probably inspired by his family and also by the people he was communicating and working with online. Aaron happened to be directly connected with some internet luminaries. People like Lawrence Lessig and Tim Burners Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web. Tim Burners Lee gave away the World Wide Web for free, famously. It’s really the only reason we have the World Wide Web today. There are plenty of ways that Lee probably could have profited from it, but the idea was one massively linking thing, not separate domains of networks — AT&T with their own, Verizon with their own, that charged admission if you wanted to link between them. It’s one of the great inventions of the 20th century. One of the greatest moments of modern history is Tim Burners Lee giving away that technology for free. I think that Aaron was inspired by that and understood that there was a kind of broader use for the web that was worth fighting for.

Sophia: Aaron said that it was important to ask yourself everyday, “What is the most important thing that I could be working on in the world right now?” As a filmmaker, do you share his approach?

Brian: I do share his approach. I think you have to go after the stories that matter to you, stories that you think are relevant to the world. Otherwise, why do this? The simple tools of filmmaking can be incredibly powerful for bringing awareness to big issues that effect everybody’s lives. If you can make films that bring awareness to the big issues of our world, if you are capable of doing that, then what is your excuse for not doing that?

Sophia: What were some of the biggest challenges of telling this story as a filmmaker?

Brian: I was eager to be responsible interviewing people who had just lost somebody that they loved. That was on my mind the whole time.

But the hardest challenge was that I really wanted the government to talk to us. I would have listened, just listened. I would have put their case in the film. I actually try to do that in the form of Oren Kerr. The government shut us down, I think to their shame.

I wanted the government to talk to us about what they did in this case. We don’t know. There wasn’t a public trial. Some documents are public knowledge, and some have been wrestled out through the freedom of information act. Why did the government go after this kid for two years? — While we were in the middle of a financial crisis where the people that perpetrated this awful financial crisis have barely skipped their dinners with the President to see the inside of a courtroom? I don’t understand that.

I think Aaron was disruptive to the powerful and their world.

The kinds of issues that Obama ran on — transparency in government, freedom online, net neutrality, online grass roots organizing, that Obama took advantage of in order to get elected, these are all things that the justice department of his administration has cracked down on.

Sophia: Obama has portrayed himself as the protector of the underdog, the backer of the David in the match between David and Goliath, yet the choice of cases and the manner of prosecution by the Department of Justice seems to belie his professed ideology.

Brian: Now we know that Obama’s posturing as a backer of the underdog, as a supporter of transparency in government, and as a friend to the internet and information in participatory democracy, is a charade. The veil has come down. It is not everything that he promised. In fact, he has done just the opposite.

Sophia: You begin the film by quoting Henry David Thoreau in regards to civil disobedience: “Unjust laws exist; shall we be content to obey them; or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded; or shall we transgress them at once?”

Brian: I chose that quote to start the film because I think that probably a lot of activists find themselves asking that question right now. What to do in the face of unjust laws? Do you just live with them? Do you live with them while you are trying to change them? Or do you transgress them and just immediately start to break those laws?

When you look at the broad range of things that Aaron was involved with, he was kind of dancing around that line a little bit, while most of what I think he was doing seemed to involve working within the system.

Photo by Quinn Norton, courtesy of filmbuff + Participant Media.

Sophia: What unjust laws was Aaron trying to overturn that he got cited for?

Brian: I think he saw injustice in a lot of different places online. At the heart of his legal troubles was his support of the Open Access Movement. The notion that academic research — the fruits of labor of the best minds of our generation and of our world — should be locked up in an ‘Ivory Tower’ away from people who need it, who can devise solutions and save lives. The notion that all that information is almost entirely out of the hands of the developing world, and that even the average person in the developed world has to spend $50, $60, $70 dollars a pop, just to look at an article. If you are doing any kind of real research, you are spending serious amounts of money. And all of this [privatization of information] is tax-payer funded. Some of this [intellectual property that is being sold] is in the public domain. So the idea that there are people profiting off of this stuff, Aaron thought was particularly unjust.

Sophia: The quote by Thoreau continues and it asks, Why does the government “not cherish its wise minority? Why does it not encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point out its faults, and do better than it would have them?”

Brian: The nature of a participatory democracy is that you are questioning the way that you are governed and that you are looking for better ways to do things. How do we do that without knowledge and understanding of how the world actually works? What is our relationship with our government? What is the nature of how they are searching our devices and communications? What is the case that they are making for transgressing our own constitutional rights? But even beyond that, what is the knowledge of how the world works? If we don’t have an idea of what our government is doing, we can’t govern ourselves.

Sophia: Aaron’s dad works as a consultant for MIT. Yet MIT never requested that the government drop the charges against his son. Did this create a conflict of interest for the father that he ever acknowledged to you?

Brian: It is a huge sense of anger and frustration for his dad. He has been a relentless critic of MIT since the beginning. MIT has a lot to answer for in this case. They are the perfect entity that might have stood up with the moral authority to demonstrate some real leadership in the resolution of this situation. And they just didn’t.

Sophia: Why do you think they did nothing?

Brian: Lincoln Labs gets a lot of government funding. They even patted themselves on the back about how much they were cooperating with the government in this case. They talked themselves into an absurd situation. It is a set of behaviors that comes out of an institutional mentality, that never stops to wonder what the right thing to do is. They decided that their own protection was the most important priority. The faculty and the students of MIT have been incredibly supportive of the film. I sense in that community, a genuine sort-of soul searching and trying to understand how they can do better. There is no question, we have had some really wonderful discussions with students and faculty. The administration wants us to go away. They want this story to go away. The General Counsel would rather not talk about this.

Photo by Quinn Norton, courtesy of filmbuff + Participant Media.

Sophia: What is Aaron’s Law?

Brian: Aaron’s Law was put forth by Senator Ron Wyden and Representative Zoe Lofgren to reform some of the worst parts of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), which has not changed since it was enacted in 1986. The CFAA basically says if you are doing bad things on the computer, the government can prosecute you criminally. One of the things that it does is that it criminalizes Terms of Use violations.

Terms and conditions – we all click on these things every day. We rarely read them all. But not biding by those agreements can be a federal offense. Facebook is a private company. You are a private individual. This is a contract between two private entities, and typically, when a private contract like that is broken, you resolve it in Civil Court. But breaking that Terms and Conditions is a federal offense. Some Terms and Conditions say you can’t lie on our website. How many people have lied on a dating website? About their age, about how attractive they are? Technically, that is a federal offense. During the making of this film, we discovered that the Seventeen Magazine website had Terms and Conditions saying you had to be eighteen in order to read it. We tweeted this out, and they changed it immediately.

Sophia: You have commented: “We all lead networked lives built on a skeleton that is inherently insecure, and it is changing who we are and how we live.”

Brian: We all live these massively networked lives. The structure that those lives are built on, which is the internet, is inherently insecure. This is the truth of our modern world. The problem is that the internet will never really be secure and still be this same internet that is built for a flow of information. Really the invention is “linking.” So anytime there is an attempt to cordon off information or to protect even things like credit cards, it’s always an imposition of something that is not in its nature. It is a heavy-handed way of forcing it to do something that it is just not really built to do. There are technical solutions to things like stopping the government from spying on us. It turns out that encryption tools are actually pretty good for confusing that flow of information. But I think that part of the solution has to be in the realm of laws. Those laws have to be protective of the average citizen, and that average citizen has to have a voice in forming those laws.

Sophia: This was a Kickstarter funded documentary. Was it your first Kickstarter funded project? What was that like?

Brian: This was the first time I’ve ever used Kickstarter to fund my work. Kickstarter is amazing and a ton of work at the same time. I think it is rare for an entire film to be funded on Kickstarter. I was going to do two Kickstarter campaigns, and midway through the first one, I knew I wasn’t going to be doing a second one. So we had to find other ways to finish funding the film. More than the money, what is great is the kind of community that develops. Fifteen hundred and thirty-one people donated to our Kickstarter campaign, so now there is this built-in audience of people who are already passionate about the project, which is a good thing.

Sophia: What does the world lose out on, do you imagine, from the tragic loss of Aaron Swartz?

Brian: When we lose somebody that is actively dedicating their lives to understanding the world better, understanding technology and how it is changing us, understanding our relationship with our government, someone who has the intellectual curiosity to really see what is happening in the world, the way things work, and is actively trying to change them — when we lose somebody who is dedicating their lives and their skills to all of that, we lose a lot.

Most people tend to live in a kind of daily grind, in which they’re only concerned about earning money and paying bills, a very limited number of things, and they don’t stop to ask how can their skills be used in the public good. So when we lose people who do think about that [bigger picture], we lose everything.

Photo by Noah Berger, courtesy of filmbuff + Participant Media.

Top Image: Aaron Swartz, “The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz.” Photo by Quinn Norton, courtesy of filmbuff + Participant Media.

“The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz” Official Website