The city of Los Angeles conjures up a lot of images for folks, and I’d imagine that, for most people, none of those pictures are connected to the literary arts. Los Angeles is able to boast being home to some of the wealthiest entertainers in the nation world while holding the title “homeless capital of America.” Outsiders envision a land of red carpets, beaches and (maybe) riots. No one considers writers like Bukowski, Ray Bradbury or Wanda Coleman; they get overlooked in favor of the flashier forms of entertainment. To top it off, there are people wandering up and down Hollywood Boulevard dressed up like Spiderman and Big Bird. It’s a weird place.

In 2014, poetry in Los Angeles took a huge step forward, crowning the city’s first ever Youth Poet Laureate. The effort, launched by Urban Word LA and the LA Arts & Athletics Alliance, has garnered support from PEN Center USA and the Academy of American Poets, to name a few. Amanda Gorman, the city’s inaugural youth laureate, is cheery, confident and articulate – great attributes for an emerging poet. She is also the founder of One Pen One Page, a nonprofit organization, and a contributor to Huffington Post. Not bad for a junior in high school.

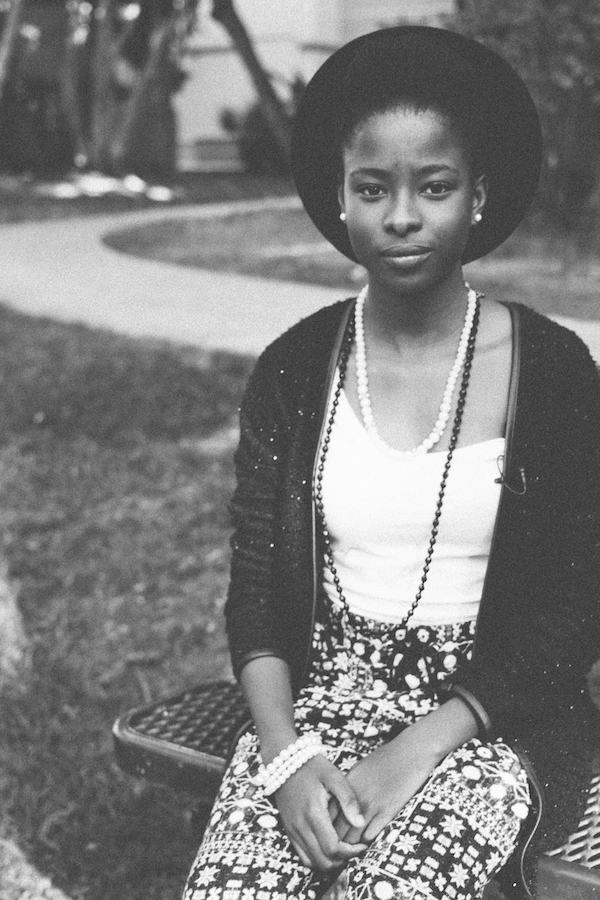

I had the chance to sit down with Amanda in the courtyard of her apartment complex and talk with her about writing her debut collection, race, violence, speaking out in spite of a speech impediment and growing up in this fascinating city she calls home.

Brandon Jordan Brown: I’m really interested, when I talk to artists, about what led them up to this moment. Do you feel like there were any defining moments in your life that really stand out?

Amanda Gorman: When I was in 3rd grade, my teacher would read Dandelion Wine to us, and it was just one metaphor that Ray Bradbury used, something about candy canes, something very simple, but I remember it just set such a fire to my mind. And I was only 8, and I was like, “Oh my God. If he can relate a candy cane to this, what stops me from relating a tree to that?” And all the sudden, I just felt filled with this creativity, and especially as someone who was young and had a speech impediment, I was like, “there’s no boundaries to my communication skills, no matter how, vocally, I express myself.”

Brown: Who were some early writers that made you go whoah?

Gorman: Maya Angelou, because that teacher also had a quote from Maya Angelou on the board all the time which was like, “People may forget what you did, but they always remember how you made them feel.” And that quote, to a young girl, made me realize how much words can change how you feel and how you sense your environment. Even to this day, I feel this specific connection to Maya Angelou, as a lot of us do, and whenever I feel lost in the world of writing, I try to look at the light that she shone on the job that we do as writers.

Brown: You made mention of some really positive moments where literature, writing or creativity brought a lot of joy and satisfaction, but as you just mentioned, there’s a lot of pain and there’s a lot of pain that you really shine a light on. In your life, personally, do you feel like there were any dark moments or tough moments that illuminated your life as an artist?

Gorman: Maybe the divorce of my parents, and that’s not something I remember, but the rupture and the chaos that that caused afterwards, right when you’re born into this world, and to be born into that kind of dysfunctional or chasm-filled family, I think, that presented in itself many moments of sadness and maybe sometimes joy with my family, but a lot of pain. So maybe not a defining moment, but that was just a big deal. Having a speech impediment definitely had its sad moments, especially when I was applying to be the laureate, because I was like, “They won’t want me to be the laureate, because I drop my Rs, and there are some letters that even now I don’t say that well, and it gets me irritated because I’m reading poetry.” I’m like, “Not only am I new to slam poetry, but these people can say words that I can’t say the same way. What if people don’t understand me?” So I was like, “Should I not apply?” I was very nervous and I was sure that I wouldn’t get it because of the way my voice sounded, but in the end, that didn’t matter, and I felt really touched that the judges were able to see that I do have a soul and a spirit that I can be the laureate despite the way I sound.

Brown: I heard an author say one time, “We’re all writing to figure out where we came from.” So, being in family that has separated, do you feel like that has been something that has been difficult to examine? Do you feel like that’s made your writing harder, to feel that? Or do you feel like you’ve taken it in stride?

Gorman: I’m going to answer that question in two parts. Part one is: at one time it makes my writing easier, because growing up in that lifestyle makes you very adept at sensing people’s emotions and sensing personal challenges and sensing relationships, and that’s just such a significant part of being a writer, at least for the writing I do. But at the same time, it makes it very difficult for me to write about myself. So you can write about the world and the things I observe and the students at my mom’s school or the people I see in my classroom, but when I was writing my book, one of the things I realized was that I barely had poems about myself. And it was really hard for me to self-reflect on my situation and revisit that pain and that suffering, because it’s not really a moment or a place that you want to withdraw to. So you have to find the courage not only to talk about the world away from myself, but talk about my origins and the place I came from.

Brown: Do you have an overarching narrative for [your upcoming book], or do you want to keep it pretty hush-hush? How much are you willing to divulge about the project?

Gorman: [chuckles] Oh, the secrets! I think it’s just really my narrative – being a girl in this world and who that is, and also reaching out and observing the world like I was saying before, starting with my story and my origins and being brave enough to confront that, and then moving past that into how I see the world.

Brown: Do you have a working title for it?

Gorman: I do. I’m not sure this is going to be the final one, but it’s called The One for Whom Food Is Not Enough.

Brown: You really explore the struggles of what it’s like for many people to grow up in an urban environment, in Los Angeles in particular – LA isn’t really a place known for poetry or literary arts. There’s a lot of entertainment, but not a lot of emphasis on literature. What do you feel like, right now, is the state of literature in Los Angeles?

Gorman: I felt this difference when I was looking at poets when I was first applying for the laureate program. I looked at New York and San Francisco and you had this different vibe. And while we do have poets in Los Angeles, it’s kind of this really different culture that you see – San Francisco versus New York, New York versus San Francisco – so I think the literary status in Los Angeles is an interesting one, because we have a lot of artists and we have a lot of entertainers, so we have this weird and intricate and awesome mixture, where you can’t really say it’s a poetry city. So I would say that Los Angeles is this amazing fusion, where it’s almost like tasting food. You take a bite, and it’s poetry, but at the same time, there’s a little bit of dance in there, and if you take the next dish, there’s a little bit of performing arts in there. So that’s where I think Los Angeles is at, and that’s why I feel glad to be the laureate here, specifically, because I’m able to represent not only poets but also youth and activists and social justice at the same time.

Brown: There’s a quote you mentioned I saw in your speech when you were awarded as the laureate, and you said, “I don’t feel like I’ve won. I feel like we have won.”

Gorman: Yeah.

Brown: So, how is this a win for the city? How is this a win for artists? How do you see your role feeding the life of LA art?

Gorman: I thought it was a win, and I still think it is a win for Los Angeles because we finally have this opportunity to really recognize the youth in the community. So while I’m the first laureate, it’s, at the same time, looking at what can happen and the possibilities that youth will be able to embrace through the program. And it really illuminated all the talented and artistic students we have driving Los Angeles and the connection that they can have to adults as well – for example, Luis Rodriguez, the “adult laureate.” So I felt that it was a great time and a great moment to look at all the faces of the youth who are here today and look at the pieces and how powerful and moving they were, and if we continue this, how great this can grow and become something that we look back on and think, “Wow, what a great moment for Los Angeles.”

Brown: Where do you see poetry headed in 5 or 10 years in LA and the nation? Do you see any trends happening? Anything you’re excited about?

Gorman: I’m not clairvoyant, but I feel like there’s a growth in poetry going on right now. For a moment I was scared – I had an article about this [in Huffington Post] – I was worried that technology and our involvement [in it] would take away from the power of poetry, but then I started realizing when I was applying as a laureate that it’s really helped spark another movement.

Brown: Yeah, I feel like poetry is, at the same time, growing and shrinking. The amount of people that turn to or read poetry is smaller, but at the same time, more poetry is being written and published than every before.

Gorman: Yeah.

Brown: So how do we get poetry back to a large audience?

Gorman: I would say connect it to things that are going on right now, whether that’s technology, seeing how you can reconnect poetry to that growing platform and branch, and also–like I was talking about in Los Angeles, I think Los Angeles isn’t the biggest poetry city, but at the same time, when I do go to poetry events, I do meet poets. It’s not just them standing as a poet, it’s them standing as a poet who knows dancers and who knows these programs and has this going on in this school, so there’s a lot of connections that they make so that it’s not just poetry standing alone, but it has this four-pillared table – how would I phrase that? It’s supported by other mediums, so I think as much as artists can connect, we should try to do that more so that it becomes not only a movement to reignite the fire for poetry, but to reignite the fire for arts and for dance. Because if we do that, then it becomes this collective, universal, inclusive movement and involvement than we’ve seen before. And then the group of people involved in poetry will start to grow and have a more diverse audience and community.

Brown: Do you think it’s more important that people get engaged and write or express themselves, or more important that people write well? Do you want to have everyone do it, or do you want to protect the art form and keep it safeguarded to where people understand how to do it the right way?

Gorman: Oh, number one. No brainer. People may have different opinions, maybe, and I think while conserving poetry is good, poetry is like culture and society – it’s forever changing. We can’t expect it to be solid and stiff, almost like stone. It’s very fluid and it is affected by violence. It’s affected by emotion. It’s affected by our beliefs and values at the time, so I think that there’s no way for poetry to be right, because the right way that may have been in Shakespearean times may be completely different than an urban child’s experience writing about his home life. So it’s changing and it’s various and it’s diverse and there’s no right way, so instead of focusing on the structurally right way to do it, we should focus on “what’s the most communal and most involved way we can be with each other.”

Brown: Yeah. You talk a lot about community, I notice. Do you view yourself more as an artist or an activist?

Gorman: I see myself as an activist who manifests her passion through art. One, because I’m not the best artist. I’m not the best poet, and I’m not the best dancer. Not that you have to be the best, but when I look at that and how much time you put into things, I put in a fraction of the time that I do into activism. So even if I’m working on a poetry piece or a dance piece or something that’s focused on social justice, the main epicenter of my reason for doing it is social justice and not necessarily because I want to be good at dancing. I want to be good at dancing or poetry or art in the context of social justice.

Brown: Right. How significant do you see your receiving this honor of being the first ever Youth Poet Laureate and the fact that you are a black female?

Gorman: That’s very interesting. I want to say it’s an interesting way to start, because it provides a different narrative and a different challenge to mindsets than perhaps having someone who’s male and of the dominant race – not that that person can’t be the laureate, because that person may have good talents and skills, but at the same time, my experience as a black female American will bring something to the laureate program that may not have been received had it been someone else. Not that you need to be of a cultural background or look a certain way or anything, but when I’m writing, all the sudden I find myself diving into those topics and really bringing them to the forefront. And I noticed that maybe in other circles or other honoring programs such as the Oscars or other places that are very politically oriented, you don’t see those issues being brought to the forefront. So me being a black American, I can really ensure, especially in the time of Michael Brown and police violence, I can really ensure that that specific cultural voice is heard.

Brown: So as a writer coming from your particular background, do you see it more as a privilege or a responsibility as a poet, to present that alternate narrative than the dominant narrative in America?

Gorman: I think, like I say about a lot of things, I think that it’s a blessing and a curse. Because I love this opportunity. It’s so great, and the people I get to meet and the things I get to do are great. At the same time, I’m constantly having to confront this fear about what people will think about what I say and how I will go about navigating these issues, because even in a classroom environment, it’s hard to talk about, let alone saying something and knowing people are going to see me and hear that and reflect it on the laureate program. For example, I was on Twitter, and I was posting things about the Antonio Martin protests, because they looked a lot like the ones in Selma. So I posted the two next to each other, and all these very conservative, racist KKK members started contacting me on Twitter and sending me mean, angry messages and things like that. So I think, as a black female, there’s this challenge of bringing not only feminism, but maybe what some people call black feminism, and bringing racism to the forefront, and you are always making yourself vulnerable. And I think, specifically, I’m always being vulnerable to being called, what you would say, “the angry black girl.” And I finally had to stop and realize that if those people don’t want to participate in the conversation, I don’t need to change my opinion in order to fit their ideas of me. At the same time, it’s okay to be the black, angry girl as long as I’m the black, angry girl and a loving girl. Because in my poetry specifically, talking about these neighborhoods and things, it may seem that I’m angry, but I try to endorse this image of myself that I am loving. I’m not condemning these neighborhoods. I’m trying to shine lights on the beauty of them amongst this pain and suffering.

Brown: I would like to revisit the importance of linking whatever art you’re using to whatever is going on in society around you. I would love to hear you speak about some of the tragedies that we’ve experienced as a nation with violence and their connection to race and to hear what that’s done for you, especially in the middle of working on a book. Do you feel like there have been any moments where the train has almost gone off the tracks or had to switch rails because of the things that have been going on?

Gorman: That’s a lot. One of the things that the recent events of police brutality did to me is that it made me very sad. It made me depressed. For me, it was very specific, because I know that I’m not someone who wants to stand by and watch it happen. I’m someone who wants to fight and try to stop it if I can. It felt like when I heard the non-indictment [related to Michael Brown], that I had walked in front of a train and been hit, because I’m trying to stop this train. I’m trying to do it, and it’s so powerful, it’s just my frail body against this huge metal systematic object that I can’t stop, so it made me feel very powerless. And that was a big grieving process for me in the middle of writing this book, and then I started writing this poem called “If I Were to Have a Son,” and it made me have to go through this grief process of being scarred and being hit by that train, but then getting up and realizing I’m not stopping the train alone. I’m not the only one who has their hands on the metal, trying to stop it from speeding up. There’s other people joining me, so in writing this book, a new theme came to me: not only me as an individual, but me as a part of a community and a sense of fighting what seems like a losing battle but fighting it anyways. Because I think that’s what real activists are.

Brown: What does it look like growing up in LA? Being a teenager in LA? Coming of age here? What has that been like for you?

Gorman: It makes me feel like I’m a quilt with all this patchwork of different things, because Los Angeles is almost like you stepped on something and made a pancake, then all the sudden all the ingredients are spangled everywhere. There’s some eggs, there’s some milk, there’s some sugar, maybe a little bit of cinnamon. So when you’re walking through Los Angeles and you’re living through Los Angeles, it’s very hard not to pick up on this diverse and varied experience that people have in the city. So I can’t just say I’m “this” type of person, because through the experiences and people you meet growing up in Los Angeles, you come up with such a different culture than you may feel in a landlocked city in the middle of somewhere that doesn’t have this entertainment or artsy vibe to it.

The last two photos of Amanda Gorman by Dru Korab