If love makes the world go round then I guess that sex must be the fuel. Though certainly one of the most universal of bonds between human beings, at times it seems that vast cultural divides in our attitudes toward sex separate us wider than the parting of the Red Sea. Crossing through these waters safely is as fraught with tension as ever for members of the tribe.

In a rather courageous move, the Hebrew Union College Museum in New York has mounted an exhibit examining attitudes towards sexuality within Judaism, called “The Sexuality Spectrum” (see catalog here). The exhibit is housed in the Rabbinical College of the Reform movement, the stream that is regarded as the most liberal in its outlook. It is running for the course of the entire academic year.

In the name of full disclosure, I am one of the participating artists in the exhibit. And I am an Orthodox Jewish woman.

In all fairness, this will not really be an art review of the exhibit; it is inappropriate for me to review a show I am in. This will more closely be a kind of anthropological study of the art works I found that most affected me when visiting the exhibit, an orthodox voyeur out of her element.

Please understand that I am not the poster child for Orthodox women, some would describe me as “orthodox lite” (this is generally not a compliment) since I probably don’t dress too differently than the general public and do not cover my hair, but the observation of the Sabbath and holidays, kosher dietary laws and other aspects of orthodoxy, including a familiarity with the waters of the mikveh (ritual bath) have all been part of my personal practice. As an artist, I am also somewhat of an anomaly in the Orthodox world, though I find this to be less unusual than once.

Social activism was at the germination of the exhibit. Frustration and a sense of powerlessness propelled curator, Laura Kruger, to mount the current exhibit at HUC. In 2011, the NY State Legislature was voting on “The Marriage Equality Act.” When confronting her anger that other fellow human beings may be refused the right to marry, besides writing a donation check or showing up at a demonstration – she funneled that anger into amassing artwork for the current exhibit at HUC.

The movement for Reform Judaism, over the course of the past 40 years has taken upon itself a willingness to be inclusive of Jews of all sexual orientations – this despite a biblical quote which is understood to prohibit sex between men, as well as a discouraging attitude towards any non-heterosexual sex practice. Traditional Judaism only recognizes sexual activity between a man and a woman within the sanctification (kedusha) of marriage according to Jewish law, and there is a practice of sex separation during a woman’s monthly cycle considered a fundamental of marital life, as well as other limitations.

Kruger spent a year seeking out artwork that would address presumptions about gender, and chose works that provoke thought and challenge traditional Judaism. Avoiding the highly explicit or art that would be offensive to any of the streams of Judaism, she hoped to enable the open-minded and curious to view the exhibit and add to a more expansive conversation within Judaism. In my own experience, it would be an unusual free-thinker from the ultra-orthodox world that would consider the subject matter and exhibits appropriate for viewing, in a population not best known for breaking ranks over the controversial.

The curatorial premise behind the exhibit is that all sexual practices form a continuum of human behaviors and that heterosexuality is just one expression of this. When my work was accepted to be used in the exhibit, I really only had the vaguest idea of its parameters. The press release for the show’s August mounting appeared, announcing:

“The HUC-JIR Museum staff held numerous focus groups of artists, asking them to share their intimate feelings concerning their lives as LGBTQI in the community, including their faith-based experiences…. They shared their long years of concealment as well as the wrenching experience of ‘coming out;’ their relationships with family members, employers, and friendships that disintegrated; and the search for life-long partners.”

I live in Jerusalem, geographically and culturally distant from the NY venue. I was not aware of these meetings, and further, I live in a city that, while there is certainly a gay community and some of its members are no strangers to me, people I admire and respect, it is a city which rarely wears its heart on her sleeve. Jerusalem is a fairly conservative city, in dress and in religious outlook, for Jews, Christians, as well as for Muslims. Holiness is to Jerusalem what baseball is to other cities. Not everyone is a fan, but you cannot be unaware of its presence.

I confess, the first thing I did when reading this quote from Kruger, was to Google the letters LGBTQI to find out the range the exhibit was covering. And, I had to ask myself, too, what does it say about me that I, as an orthodox woman, am participating in this exhibit that does not follow my stream of Judaism’s outlook and beliefs? Would I be sorry I had agreed to join in? It was with mixed feelings that I attended the October opening of the exhibit.

The Jewish Quarter in the Old City, where I have lived over three decades is no longer the pluralistic neighborhood that drew me to make my home here. A very small secular presence of families still exists amongst a large orthodox block. Though there are many stripes within the block, the distinctions are nuances known more to the residents than to outsiders who would see it as a monolithic unity of orthodox Jews living in the community comprised of 600 homes.

It was from this world that I crossed into the cultural milieu of the exhibit location, bordering the East Village of Manhattan. Exiting the subway, I passed names like Bleecker Street, Fourth Street, and other echoes of my early music heroes Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel and others; I passed the NYU Law School campus near Union Square to the doors of the HUC Museum.

Typically for me, I was running a little late, and I arrived with the opening well underway, which eventually climbed to over 500 attendees. While no surprise in NY, it is far in excess of the more modestly attended openings one gets used to in Jerusalem. Size was not the only difference. A quick glance around made it clear that I was far from home. There were the expected kippah-wearing women, a phenomenon that, while not common, one does see occasionally in Jerusalem. There were also same sex couples clasped in hugs and intimacies that are very uncommon to see in public in Jerusalem, not to mention that any public displays of affection between heterosexuals are frowned upon in some religious circles. Long-skirted women, the black suit white shirt and tie – worn as a uniform, men’s beards and hats and women’s wigs which are so ubiquitous in Jerusalem were notable in their absence.

The speakers included a dean of the HUC Rabbinical School, who introduced herself as a Rabbi and feminist Thinking of her remarks and demeanor were in my mind when I later saw the exhibits. Amongst them was a photograph by Joan Roth, called “Gay Wedding” of a wedding between two women in a Jewish sanctuary; their joy was obvious. Jerusalem weddings are “same sex” only in the sense that the dancing or the dinner might be separated by a mechitza – a barrier to prevent social mixing of the sexes, designed to reduce temptations and ensure fidelity to one’s spouse, but definitely not a same-sex couple marrying. Permission to marry is entirely within the purview of the individual religious authorities; Jews needing the approval of the Chief Rabbinate, an orthodox body, whose authority is often criticized, even prompting a trend to wedding tourism to Cyprus since no civil marriage exists in Israel. By this time I knew that I was not in Kansas anymore, but in an environment that was sure to jiggle my comfort zones.

I returned another day to leisurely examine the exhibits by 57 international artists, in addition to collateral pieces culled from cartoons, magazines, and from other popular culture sources. In conversation with the curator, Kruger elaborated on her motivation to examine these controversial subjects through art. Referring to the caustic rhetoric surrounding the passing of the same-sex marriage bill in NY, she said:

“Prejudice and discrimination are blinding neon lights – no different than what the Nazis said about the Jews in 1938. What would be next?”

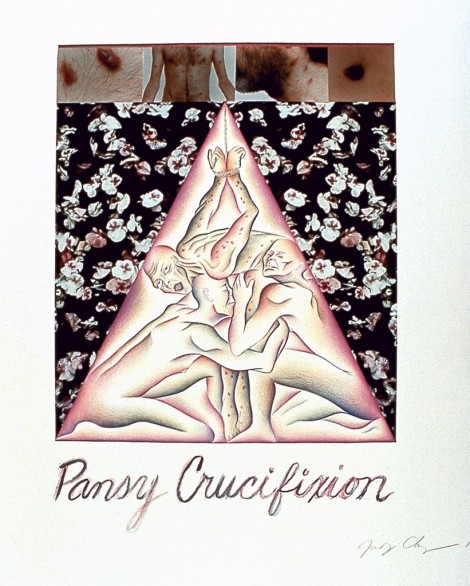

Indeed, the exhibit includes works which referenced Nazi persecution of homosexuals in World War II by Richard Grune, Estelle Yarinsky, Linda Soberman and Judy Chicago. Perhaps best known for her iconic installation, “The Dinner Party,” Chicago’s 1979 installation shook up the art world by focusing on accomplished women through history in individual table settings based on a variation of the triangle- a symbol for the vagina. Here, in “The Pansy Crucifixion,” the triangle was used in a different context entirely, the pink triangle which was used in Nazi concentration camps to designate homosexuals, (much as the yellow star, a double triangle, designated Jews in the Nazi lexicon of dehumanization) and connected that symbol of shame to the AIDS illness that continues to afflict so many. The work includes three male bodies cramped within the triangular space, contorted in suffering but also, perhaps, alluding to gay love. The pansy flower visually echoes the sarcoma lesions of the illness and the pejorative insult used to describe gays, the various associations ringing sadly true. German Grune’s work, a 1947 lithograph, serves as testimony to his own incarceration as an “undesirable” homosexual under the Nazi regime.

Helene Aylon, a pioneering feminist artist, exhibits her piece which magnifies the biblical quote calling homosexual relations an abomination. This is one of the sources for Judaism’s position which prohibits homosexuality. From there, the exhibit investigates many artists’ approaches to the world of the forbidden, the marginalized and gender presumptions. With many works to ponder, the exhibit would benefit by a more spacious setting and more clear delineations for the groupings of subject matter.

Some of the works which examine gender presumptions include Lewis Cohen‘s “Ironing it all Out” where domesticity is represented by the mundane act of women’s old fashioned manikin hands ironing a man’s shirt with apologetic and conciliatory phrases imprinted upon it. Stressing the anachronistic in his choice of wifely duties in these days of permanent press, Lewis’ work does serve as a reminder of the traditional subservience of women in the home and the still relevant tensions of individual’s accommodations in marriage, sometimes sacrificing personal esteem at the altar of marital “success.”

British Jacqueline Nicholls presents delicately executed paper-cuts in the form of doilies that once lined the platters at synagogue social events, and exemplified the only possible aspiration for female congregants in the all-male-run synagogue of her youth: attractively presenting refreshments. On closer inspection, “The Ladies Guild: Temptress” is formed by various lace-like nude women hiding their body parts as they surround a rabbinic quote where a virgin is said to pray that she not lead men to sin. Never mind that any sinning would derive from the mind of the man, and that she is left feeling self-conscious about her young body and shame.

Of particular interest to the Orthodox community should be the work by Israeli-American Andi Arnovitz, “4 % of Us.” In this work, a tabletop vitrine is filled to the brim with multiple clay paper objects denoting tiny fetuses in utero. For Orthodox couples who scrupulously adhere to the practice of separation following a woman’s menstrual cycle, it is known that 4% of women cannot conceive since they ovulate during the prescribed time of separation. Arnovitz is anxious to have the rabbinic authorities adjust the strict interpretation of the law to take into account this avoidable loss to couples who seek to fulfill the biblical mandate to “be fruitful and multiply.” While the Orthodox may well identify with the injustice of this issue, and even agree with the artist that a new interpretation is warranted, will that sense of outrage carry over to other strict interpretations and injustices that this exhibit addresses?

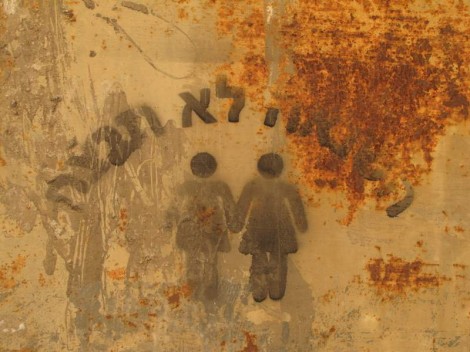

With your indulgence, I will discuss my own works in this exhibit. After moving my studio to Nachlaot, my daily routine included traversing a neighborhood full of contradictions. At once both secular and orthodox, home to the down and out as well as to the upscale, it is an area that is grungy, eclectic and rich in off-beat treasures for a street photographer to mine. My four photographs which are shown document the debate that rocks around the Gay Pride Parade. Photographing found graffiti, which become visual “wall-flowers,” disappearing in the scatter of sprayed wall markings and the jumble of templates amidst neglected walls and corners, some of these spoke to me as deep truths. One, “God She Loves Everyone” seemed to flip our presumptions about the Creator, to whom we do not attribute a gender in Judaism, yet we usually refer to as male in Hebrew, a dual gender language. Probably men think nothing of this, yet this piece of graffiti causes pause in viewers as they consider the female verb choice and whether this resonates in a different, softer, perhaps more maternal way, putting the stress on the feminine attributes of God. Another, “I Am Proud To Be a Genetic Defect” shows the internalization of the vicious rhetoric hurled in the gender battles. And below, in “Hate Will Not Win” are two skirted stick figures, hand in hand, suggesting that same sex couples and human love will ultimately succeed over baseless hatred.

There were many works which addressed same sex attraction, including that of Kobi Israel in “Intimate Strangers,” an ex-pat Israeli and one of several Israelis participating in this exhibit, whose photograph “Akedah” graces the catalog cover. Unlike the U.S. Army, the Israeli army never had a policy of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, and, he notes that soldiers living as one sex together could find themselves in a circumstance that went beyond the homo social, or same gender living, such as one-sex dorms, to the homo-erotic where the joint living situation might arouse attraction, triggering identity questions in this most macho of settings. Israeli mainstream culture still employs the slang reference to gay men as “homos” without raising any eyebrows.

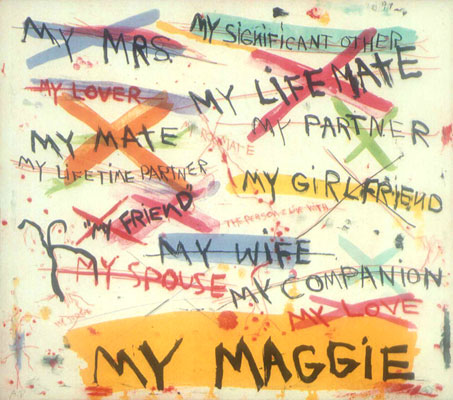

Some of the works addressed the desire for finding life-long relationships. Joan Snyder, a leading abstract expressionist painter, displays what the catalog describes as a ” very personal print” in the frank search for the proper social reference for one’s life companion, considering and rejecting each description or title till simply arriving at the proper name in “My Maggie.”

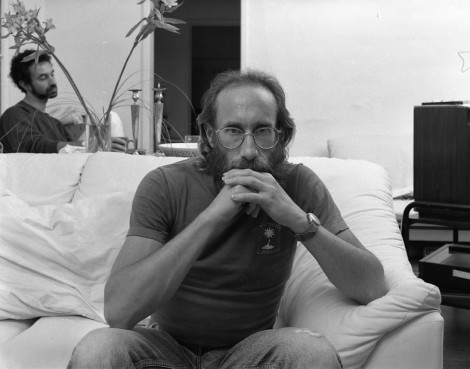

Personally compelling was a photograph of a familiar domestic scene by Albert J. Winn. In “Erev Shabbat” we see the photographer staring into the camera from the living room sofa and the typical Friday night scenario of lit Sabbath candles and flowers in a vase are on the table behind him, a scene of domestic contentment. It is another man, rather than the traditional woman/wife/mother, who apparently has brought in the tranquility to the home that comes with lighting the candles, one of very few religious obligations that fall upon women. This scene prodded me to understand that just because one’s sexual practices cross accepted norms, the desire for the weekly rhythm of the renewal in the form of Sabbath observance may be seen as just as strong a need, and that, perhaps, there is no inherent conflict in that. I couldn’t help but think: as it should be.

Once one accepts that all are “created in God’s image,” and acknowledges that people are born with different physical attributes built into our DNA, it is hard to avoid the conclusions which follow logically: all people want and need love, intimacy and home life with those that they choose. Modern science has provided solutions for those that want to raise families, one cannot hide behind the desire to perpetuate the Jewish people as a goal to prevent the establishment of non-traditional families.

Yet, religion is not about logic, it is about faith and belief. The nature of the Jewish religion for observant Jews has always included a reigning in of personal freedom by adhering to the dictates of the “yoke” of the religion, taking on the responsibilities, beyond the Ten Commandments, that the observant Jew is to follow throughout their lives, the 613 observances, a kind of spiritual GPS for life, meant to get you to your goal. Observant Jews believe first in the primacy of God, and that following the Torah and its commandments is a trade-off in passing up on the short-term, fleeting rewards of the present material world to achieve a higher level of holiness in the present as well as a delayed reward in the more significant world to come.

Just as there are restrictions on eating, refraining from consuming pork, shellfish, etc., there are restrictions on life decisions despite the inconvenience or temptation. Descendants of the ancient priests, Cohans, still are forbidden to marry certain women, such as divorced women. Relations with the opposite sex are also restricted outside of a marriage in accordance with Jewish Law (with certain rare exceptions that I won’t go into, as I am no Rabbi).

It would be disingenuous to suggest that all this willingness to adhere to such strict adherence to religious life is easy or simple for the average person. And, it isn’t always pure belief that motivates people to tow the line in their lives and abstain from the enticements of the forbidden. Sadly, there is also a strong aspect of discipline within the religion, including rabbinic courts, social pressures to conform rather than risk being shunned by one’s synagogue, having the “right” schools turn down one’s children, or the fear for lack of appropriate matches for children of marital age. Unfortunately, even self-appointed vigilante “enforcers” have been known to intimidate those who are subjectively deemed too free. Would that all followers of Judaism be motivated by the pure love of their faith. For many it is a purity of belief, but for some it is a system that they are born into and that they feel helpless to disengage from. For others, the all encompassing aspect of the religious life is too much for them and stifles their uniqueness severely, leading them to deviate from the path that they were born into, with some eventually unchoosing their People.

As any driver today knows, a GPS is not infallible. Even when followed explicitly, who hasn’t at least once found the directions faulty? Often, the instructions have not quite kept up with road maintenance changes, and by following the instructions blindly one can find one’s self “at your destination” in an abandoned field or dead end. The “reigning in” of nature’s hard-wiring leads to the known path of repression, identity confusion, teens escaping their homes to street life and homeless shelters (explored here by Joshua Lehrer), suicides, hypocritical double lives with a conventional wife and family to cover for one’s actual secret practices, and an unfulfilled wife whose own sexual satisfaction to which her marriage contract entitles her, effectively abandoned as emotional collateral damage in a marriage that is a farce.

None of this is a pretty picture. Rabbi Rachel Adler advocates re-interpretation of the Torah texts as a way out of this conundrum in her catalog essay, where she concludes:

“My hope is the LGBT rabbis show us a way people can live by these texts and not die by them… it says…”You shall live by them”- meaning by the commandments. And the rabbis comment, “and not die by them.” Not have your selfhood stifled or in hiding. Not be bullied or bashed. Not, God forbid, commit suicide. But live, pridefully, openly, and joyously.”

Is all fair in love and the gender wars? Can Judaism become everything to everybody? If the family, the most central structure of Judaism, is subject to reinterpretation, is it the same religion, or does the re-thinking morph the religion into something unrecognizable as Judaism? Will children resulting from same-sex marriages be considered “kosher” for all Jews to marry, or will the results of this new outlook just create higher ghetto walls of self-protection for the more traditionally-minded? And, for the gay children born into Orthodoxy, will their parents mourn them as they marry their gay partners, as was a traditional response by parents when their children married non-Jews? The ties that bind us, our children and grand-children, eventually won out in that scenario that was once common for the committed Jew.

This exhibit seems to be largely directed to the choir. It is hard to imagine that the Orthodox world will soon find itself sitting on the same side of this issue with these advocates for change. The sad statistics of Jewish demographics today include high assimilation rates, high intermarriage rates, and climbing divorce rates. On the other hand, amongst the Orthodox world, there is a high rate of heterosexual marriage resulting often in large families, accounting disproportionately for continuity of the Jewish people numerically, as well as closely preserving classic Jewish observance. Will more lax rabbinical interpretations of ancient texts and rattling the chain of thousands of years of tradition destroy Judaism or allow for more humane inclusion?

All this leads one to ask: Where does the future of the Jewish people lie? And with whom?

“The Sexuality Spectrum” at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion Museum 1 West Fourth Street (Between Broadway and Mercer) New York City: Through June 28, 2013

This article was originally published in The Times of Israel, with whose kind permission we have re-posted it here.