Phillip Larkin’s poem, “This Be the Verse,” begins with the line, “They fuck you up, your mom and dad.” Luke Johnson’s chapbook, :boys, recently available from Blue Horse Press, illustrates bravely and unflinchingly the moments that this is true; but it is also full of the miraculous possibilities of boyhood. In the title poem, Johnson tells how a group of boys stands around a barn

Phillip Larkin’s poem, “This Be the Verse,” begins with the line, “They fuck you up, your mom and dad.” Luke Johnson’s chapbook, :boys, recently available from Blue Horse Press, illustrates bravely and unflinchingly the moments that this is true; but it is also full of the miraculous possibilities of boyhood. In the title poem, Johnson tells how a group of boys stands around a barn

watching

fetal mice fill

their fresh lungs with air

when Smitty

behind a tribal smile

pulled a blade

from his back pocket

and began

to slice one down the abdomen

with ball point precision (1)

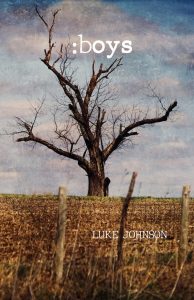

The story is relayed with an acuteness that pulls the reader into the book without promising that it will be an undemanding or comfortable read. This is one of many small brutalities in the book that make up boyhood, and Johnson is resolute in his treatment of them. In a time when the definitions of what it means to be masculine are being reexamined, Johnson’s book is both timely and necessary. The slim, soft chapbook is gorgeous and includes an evocative photograph, “Haunting the Backroads of Missouri,” by Justin Hamm, on its cover. Inside, eighteen poems (one for each year of childhood) excavate and explore the paradox that is being a boy.

These are not easy poems. Their joy comes from their lyric qualities, and from the delight that the reader gets from being steeped in their dark energies. In “Numbers 14:18,” the second poem of the collection, Johnson begins,

I’ve never told you

how my father tied

a drunk man to a chair

and snapped the first four fingers

on his left hand. (3)

This revelation feels intimate, as if the reader’s ear is being whispered into. Reading the poem again makes the revelation no less affecting, and that first line, “I’ve never told you,” creates a sense that even though the telling is difficult, it is something that must be done. The poem is surprising in the way it puts things side by side: thyme in a soup, a belt, whiskey, “an animal / crazed for water.” The way the words snap into the reader’s consciousness like the bones in the fingers, like the lines of the poem, jagged and unrelenting. But, like Robert Frost’s statement, “In three words I can sum up everything I’ve learned about life: it goes on,” the poem ends with the repeating of the phrase “of a boy” seven times, the last time with an em dash, “of a boy—” that affirms that despite the difficulties of boyhood, the boy, in all his iterations, does go on. He survives, and doesn’t just survive, but survives and writes spectacularly about it.

Here is the chapbook that is proof of that writing. which is focused and honest in its refusal to shy away from difficult topics. In “Like a Fish Gasping,” Johnson uses repetition to say again and again what happened to a boy named Jonah. The poem asks,

Did I tell you Jonah ran, never came home, his body

a house without windows?

Did I tell you Jonah ran?

Did I tell you he put a gun to his head and did what

the whispers wanted?

Did I tell you it wasn’t his fault? (19-20)

The reader might find themselves thinking, “Yes, you told me,” and it is this engagement with the reader that gives the poem the power to possibly create change in the world. As the poet asks us these questions, we are left thinking about how to answer – what to do with all of this information. If what happens to Jonah isn’t his fault, whose fault is it? How are we also responsible for what boyhood is, and what can we do about it?

In “I’ll talk sadness, sure,” Johnson offers up a list, including “daddy’s cane / frayed from blunt force,” “the cat kicked / crooked for clawing,” and “Brass knuckles” (27). These are the objects of a boyhood, set out in a display down the page. This is the clatter of boyhood, the noise, the trauma; the enumeration that comes with the idea of the colon included in the title, :boys. There is a meditative quality to the listing; and for me at least, there is room to think between the lines of the poem about what might have allowed this Jonah, or any Jonah, the ability to survive and to thrive.

Johnson’s second-to-the-last poem, “Song of the Stillborn,” seems to acknowledge that there is also a strange splendor in keeping what has not survived in our view, and perhaps to the excavation of a boyhood that was very much occupied by violence. In the poem, Johnson writes about a stillborn calf:

but there’s something beautiful about a body

picked down to its spine.

How it carries its shape.

How it softens over time. (34)

Boyhood is temporary, yet it also stays with a person; it is a root, an attachment, a memory that is inseparable from the man the boy becomes. In the final poem of the collection, “Finch,” Johnson seems to also soften, and turns toward two of his own children, a son, who “swats a finch with his bat / and laughs” and a daughter, who after the bird dies, laid it “in a wood box / and dropped a match” (35-36). Later in the poem, father and son go looking for fallen fruit “without bruised ruts or flies, / finch in the foreground singing” (37). Boyhood is the swatted bird, the ash, the rutted fruit. Boyhood is also birdsong, unbruised fruit, and this new son, who is protected by this father, who was once a boy, and who has written his own boyhood into a book. Johnson’s book is a sort of fence, a fence of eighteen astonishing poems, that allow us to view the wildfire that is boyhood from a safe boundary, while also asking us to consider deeply what it all means. At the end of “Finch,” Johnson describes one summer wildfire:

Like a lung of light. I’d wait

by the window, watching, wait

until sunrise. Listen for sounds

of my son’s feet

racing across the cloven field, forbid

him to pass through the gate.

Luke Johnson’s chapbook ends with a father who is in the act of protecting his son. Larkin’s line, “They fuck you up,” might be true, but perhaps it is becoming less true. Johnson reminds us, brilliantly, that there are many ways to be a parent, and that there are also many ways to be a boy. :boys is a breathtaking, compelling, thought-provoking read.