Brassai was more than a talented documentary photographer. He was a visual poet of the streets of Paris in the 1930s, focusing on the ordinary working people of the city rather than the elite, on gangsters and hookers and drunks more than bankers and socialites. He was in love with the night, with the velvety textures and patterns that a cobblestone street makes in the rain, with the beautiful grays of a public park on a foggy night.

His work is now on view in an excellent retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, titled simply “Brassai” and organized by the Fundacion MAPFRE of Spain. With more than 200 prints on loan from European and U.S. museums, it’s a fine introduction to Brassai’s photography.

An ethnic Hungarian, Brassai was born Gyula Halasz in 1899 in what is now Brasov, Romania. He briefly attended the Budapest Academy of Arts after World War I. By 1924, he had moved to Paris to become a painter, and by 1930 he had taken up photography.

He soon began contributing to magazines, using the pseudonym Brassai, meaning “from Brasov,” to distinguish his photography from his painting and drawing. He also began to meet other artists and photographers, including Pablo Picasso, Andre Kertesz, and Salvador Dali, and published his first book of photographs, Paris at Night, in 1932.

His “Lovers” of 1932 is an almost heartbreakingly sweet picture of a man and a woman taking shelter on a sidewalk at night. The man wears a dark suit and a jaunty fedora and leans against a lamppost, his arm around her waist. The pretty young woman, with her short hair pulled back, wears a raincoat and leans against a wall, smiling back just a bit. It’s a romantic and mysterious image, something that easily could have been a cliche if it weren’t so perfectly handled.

The exhibition presents Brassai’s works by themes, and “Paris at Night” is arguably the most interesting. In “Avenue de l’Observatoire in the Fog” of about 1937 (top photo), a car approaches out of the dark, with its headlights shining across the horizontal frame in a broad band. On the far side of the avenue, bare trees, park benches, street lights, and a kiosk loom in silhouette. This deserted, spooky image shows what a great photographer can do with a palette of grays.

Sometimes he documents small dramas of the street. In “Cat Circus” of about 1931, a man holding a baton orchestrates the tricks of a cat perched on a stool as it crouches to jump to another stool on a Paris sidewalk. A gleeful crowd of children and adults, three or four deep, surround the scene, and the range of their expressions is amazing.

A somber 1932 series features a dead man lying on a busy sidewalk next to Boulevard Auguste-Blanqui. The first shot includes a single pedestrian in an overcoat peering over the body as traffic goes by. The next shows four onlookers, with the crowd growing in later images to about two dozen. Then the body is loaded into a vehicle and taken away. The last picture shows the empty sidewalk returned to peace.

Some of Brassai’s most striking images were created in the city’s restaurants, bars, parks, theaters, and brothels. In one eye-opening series, he shows a young man — his assistant, it turns out — impersonating a client who is sizing up a group of nude prostitutes shown from behind. In other series he documents people sleeping on park benches, gangsters hanging out on sidewalks, and socialites in fancy dress at glittering dinners.

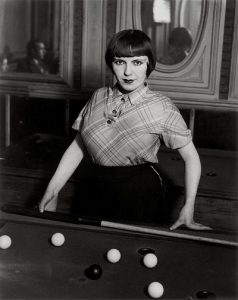

One iconic picture from 1932-33, “Billiard Player, Boulevard de Rochechouart,” shows an intense, almost scary-looking young woman with short-cropped dark hair and a tight plaid blouse standing behind a billiards table, cue stick resting in her right hand. Her attitude, somewhere between enticing and threatening, suggests she’s definitely not someone to mess with.

Brassai quit taking pictures when the Germans occupied Paris from 1940 to 1944, focusing on drawing and writing instead. He returned to photography after the war, traveling widely to shoot photos for the American fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar. Over the years he also created a memorable series of portraits of famous artists and writers, ranging from Picasso and Dali to Lawrence Durrell and Jean Genet.

In the ’50s and ’60s he traveled to the United States and, after decades of using large-format view cameras, he bought a Leica and began shooting 35mm color film. The exhibition includes a number of striking pictures from the postwar period, yet their visual polish often doesn’t quite match the emotional power of his earlier images.

“Brassai” runs through February 17 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 151 Third Street, San Francisco.

Top image: Brassai, Avenue de l’Observatoire in the Fog, c. 1937; (c) Estate Brassai Succession, Paris.