From Indifferent Observer to Informed Admirer

Perhaps with New York City’s Lincoln Center in mind, Los Angeles has created a cultural complex with a spontaneous accumulation of buildings of architectural merit along and in proximity to the crown of Grand Avenue in Downtown Los Angeles. They include: The Music Center by Welton Beckett (1964-1967), Museum of Contemporary Art by Irata Isozaki, (1986), Colburn School by Hardy Holtzman Pfeiffer Associates (1998), Cathedral of Our Lady of Angels by Rafael Moneo (2002), Walt Disney Concert Hall by Frank Gehry (2003) and Ramon C. Cortines School of Visual and Performing Arts by Wolf Prix of Coop Himmel(l)au (2008).

Recently opened, The Broad art museum by Diller, Scofido and Renfrew is the new kid on the block. Their assignment was to create an appropriate environment in which to house and view the vast and varied collection of Post War and Contemporary art assembled by Edythe and Eli Broad. Wishful thinking – hopefully it would become an architectural icon providing gratification to the clients and architects as well as adding luster to the existing group of significant buildings. From my perspective, it scores on all counts.

Many factors affected the design of this building. Lets speculate for a moment. If you were a member of the lead design team of an architectural firm that had been selected to design a building that abuts (across the street) an architectural behemoth draped with metal contusions camouflaging the building’s interiors, how would you approach this project?

Design a competitive behemoth? (Disney Concert Hall)

Design a building without character or personality? (Los Angeles Times offices.)

Design a building that is primarily practical? (The gas station in Ed Ruscha’s painting, Standard Station).

Design a building which reflects the client’s functions and purposes? (Beachfront cafés, Santa Monica)

Design a building that represents the ego of the designer? (Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers)

Design a building that will be popular with the public? (Disneyland’s Magic Kingdom)

Design a building that will please architectural critics? (That’s a crap shoot. No one knows.)

Or design a building of functional and architectural integrity? (My candidate is The Broad)

Diller, Scofido and Renfrew are the architects who gave us the incredible New York City High Line. Their assignment was to adapt an abandoned elevated freight rail line into a public park. Walking the length of The High Line is an orchestrated sensory experience involving motion, sight and sound. It is so successful that the High Line’s design is being appropriated by cities around the world. Perhaps ambulatory choreography is the best way to explain their raison d’être. Both Elizabth Diller and her husband Ric Scofido credit their exposure to dance choreography as a contributing factor.

From my perspective, a museum should be a choreographed experience that begins at the entrance and proceeds throughout the building in which visitors are exposed to and confronted with varying visual, aural and ambulatory experiences. In terms of my criteria, I cite both the new Whitney and Museum of Modern Art in New York as failures. I consider the new Whitney to be an admirable building in many ways; however, visitor experience and traffic management have been neglected. Like the old Whitney, there are two elevators, large and small, transporting visitors from the basement to the eighth floor as in a department store. The printed PLAN is distributed as a guide to visitors; however, directional signage is limited and ineffective.The Museum of Modern Art is a total disaster in terms of visitor experiences. It is difficult to find your way from floor to floor or exhibit to exhibit even if you are familiar with the interior geography of the building. Directional signage is obscure and limited. These problems are the accumulated heritage of two redesigns: César Pelli (1983) and Yoshio Taniguchi (2002). Recognizing that signage aiding traffic movement had been neglected in Pelli’s design, I was engaged as a consultant to MoMA to propose amelioration. Modest changes that had been implemented were later neglected.

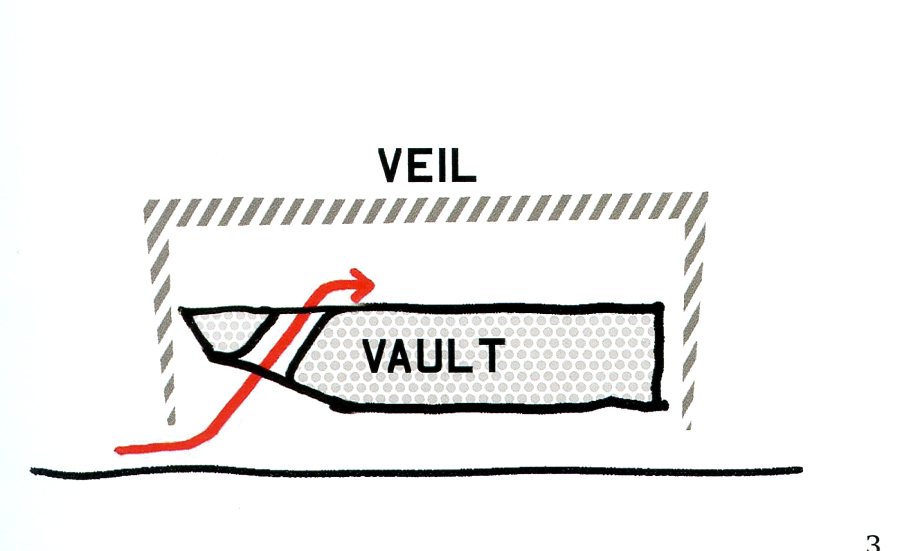

At The Broad, a choreographed visitor experience is the armature around which the building functions. Ric Scofido consciously draws parallels to the choreographed High Line visitor experience. Elizabeth Diller likes to describe the design program of the building as integrating the vault (collections’ presentation and storage) with the veil (exterior surface.) There are two entrances at ground level that feed visitors into an escalator or an elevator with transparent walls that allow visitors to view storage areas en route to the third floor exhibition gallery. Perhaps their task was simpler than traffic management at The Whitney or MoMA because at The Broad there is only one primary visitor destination – the third floor. It is a spectacular gallery, a vast open space without supporting walls or columns.

Veil/vault diagram

Here is how Elizabeth Diller describes the veil/vault relationship: “The veil and vault act together. The veil’s porosity suggests two-way vision and tempts you from the street through its lifted corners. … When you arrive on the third level, you find yourself standing on top of the vault in approximately an acre of exhibition space under the sublime diffused daylight that penetrates the veil… The presence of the vault is important in reminding the public that this is not a traditional museum, but rather the home of the distinctive collection of Eli and Edy(th)e Broad.”

Now in place on the third floor is a system of movable walls that allows for a variety of configurations. For the opening exhibition, these movable walls have been articulated to simulate traditional museum galleries. This is not a criticism of the architects, rather a lament that the museum staff chose to configure the third floor exhibition space as a conventional museum experience. Since the walls were designed as flexible components, they could be arranged in unlimited articulations. At some point, I hope that exhibition design will be less conservative and take advantage of the potentials offered by this unobstructed space. At a pre-opening event in January, I was witness to Yann Novak’s sound and light projections that embraced one wall of the then unfinished structure.

There are few, if no other museum galleries that offer the potential for such expansive presentations. The Broads have amassed a huge collection of what might be called works in traditional media: paintings, sculpture, prints and drawings. If Yann Novak or Bill Viola (whose work is in the collection) were invited to fill this space with their evanescent art, it would be an unbelievable spectacle.

Buildings are seldom evaluated on the basis of successful internal traffic management. Outside appearance is what counts. One must be cognizant of the mass of the building that is perceived from ground level, from a distance, from the air and from abutting structures. Here again, The Broad scores high on all points; however, this was not my first judgement. I thought that it was a huge, curious block of white cheese with a lot of holes punched in it. On further thought, I have learned to appreciate the ingenuity of this building as a manifestation of 21st century technology. No, it does not look like conventional buildings. Why should it when digital technologies offer so many possibilities to design structures.

Here is how Elizabeth Diller describes it: “We modeled the building in Digital Project, based on Computer aided Three-Dimensional Interactive Application (CATIA) software. This allows us to maintain control over the building form in relation to light, structure and criteria for constructability. With that software, we could work on the building anatomically, digitally build the structure, add the cladding, the glass layer, the vault geometry and other intersecting systems … The data from the computer was given to the fabricator, who used it to carve foam molds using a five-axis CNC machine. Without these tools the project would have taken a lot longer and would have been more expensive.”

In The Broad we have an honest 21st century structure that embraces new technologies and creates architecture within the parameters offered by these technologies. Others might have a first reaction similar to mine, being confounded by the design of the building. I hope that they, like myself, will comprehend its architectural significance and aesthetic virtues and embrace The Broad, as I have, with enthusiasm.