Buried by Vesuvius, Treasures from The Villa Dei Papiri, The Getty Villa’s current exhibition, through October 28, 2019, is a legitimate exercise in self-congratulation. It commemorates the vision of its founding benefactor, J. Paul Getty, who wanted to document the achievements of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome and to identify with them on a personal level. J. Paul Getty conceived his museum as a replica of the original Villa Dei Papiri of Herculaneum, buried in the 79AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius. In the mind of French post-modernist philosopher Jean Baudrillard, reproductions of historical monuments can, as symbols, replace the originals. Thus, we can say that the simulation of the Villa Papiri in Malibu has developed its own identity in conveying a sense of a world that existed two thousand years ago.

As both a cultural experience and a personal monument, The Getty Villa has become a significant player on the international circuit of major museums of Greek and Roman antiquity. The Getty Conservation Institute complements The Villa’s museum function by providing conservation services to museums which later allow their conserved objects to be exhibited at The Getty Villa. Consequently, a considerable number of objects on display drawn from major archives of antiquity will be seen for the first time beyond their established sanctuaries.

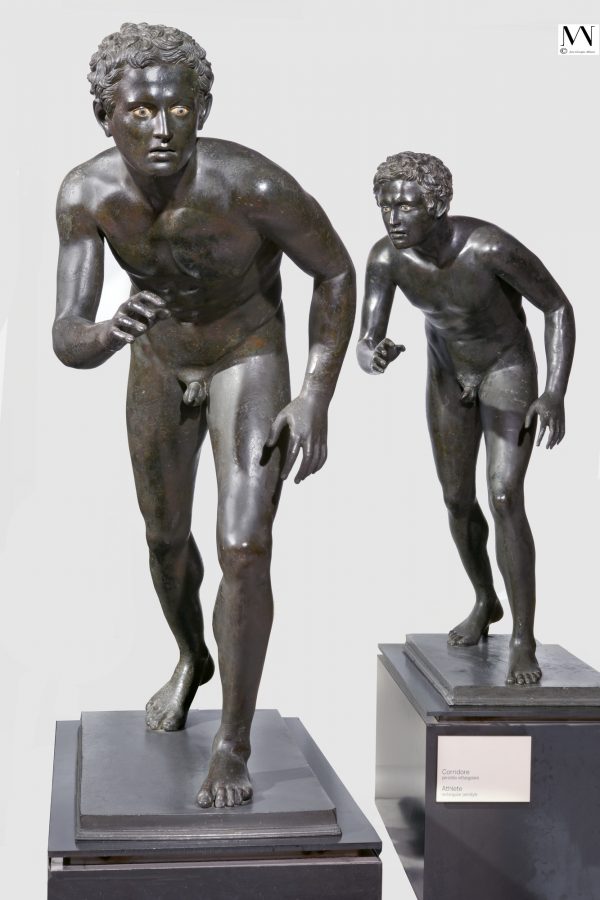

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79AD, the Villa dei Papiri, situated along the Bay of Naples in the town of Herculaneum, was buried in tons of molten lava. An extraordinary time capsule was created that provides us with an opportunity to explore the history of this epoch through the surviving artifacts excavated at the site. This exhibition provides a comprehensive presentation of many of these exhumed significant artifacts. Presenting a stunning display of Roman sculpture of that epoch, we are exposed to the largest collection of sculpture ever recovered from a building of this era

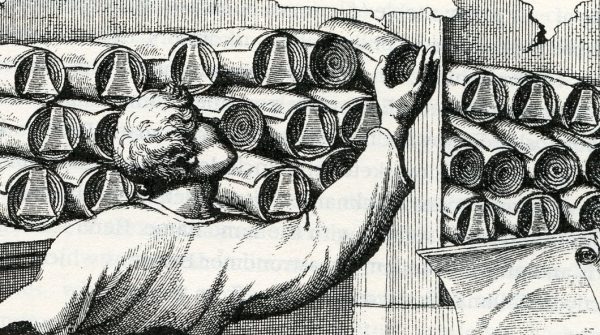

Also buried at the site was an extensive collection of approximately one thousand papiri (papyrus books and manuscripts).

Although covered with molten lava, the Villa dei Papiri’s extant collection of more than a thousand papiri constitutes the only surviving library from the classical world. For hundreds of years, there have been unsuccessful attempts to open the carbonized scrolls. One such device is on display. It is anticipated that advanced imaging technologies offer the prospect of virtual unrolling. If and when this happens, we will be witnessing a new chapter in the quest to uncover antiquity.

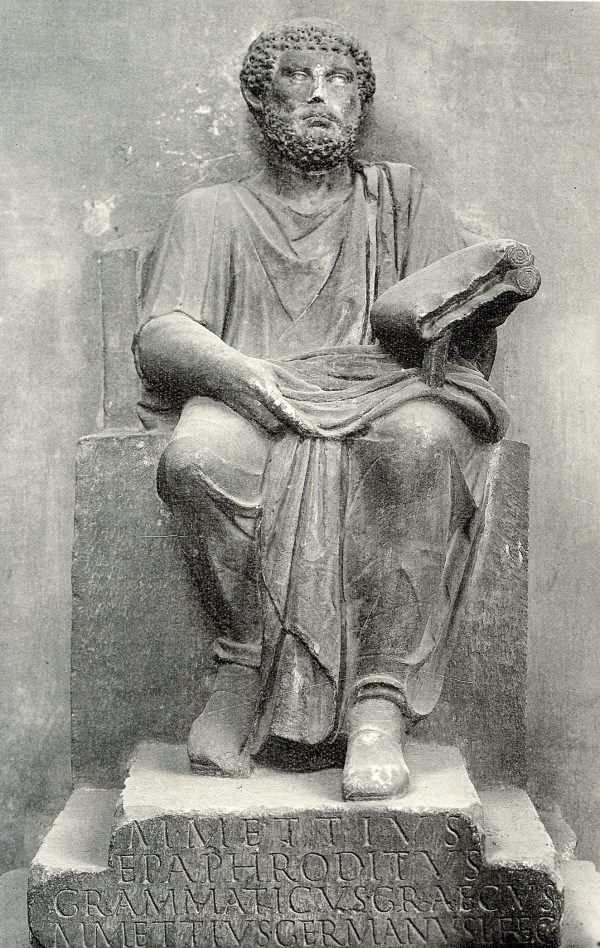

With a population of one million and blistering summer heat, Ancient Roman aristocrats exited the city and created a colony of summer homes along the shores of the Bay of Naples and on islands like Capri situated in The Bay. The Villa dei Papiri, The Getty Villa’s model, was one such summer retreat. Lucius Calpernius Piso Pontifex (42BC – 32AD) likely inherited the Villa dei Papiri from his father and might have been responsible for the building’s decorations and expansion of its library. He held high offices under the emperors Augustus and Tiberius including consul in 15BC.

This exhibition, both commemorative and illusstrory, does not attempt to synthesize the residents’ experience; rather, it seeks to amplify that experience with numerous authentic artifacts discovered at the site in the 18th century along with those unearthed in recent excavations.

A footnote on papiri and libraries in Ancient Rome

Papiri were the books of the ancient world, They were scrolls consisting of separate sheets of papyrus, a material similar to thick paper, used as a writing surface. Native to Egypt, it was utilized throughout Ancient Egypt, Ancient Near East, Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Papyrus documents provided records of these civilizations and have served as the basis for much of our knowledge of the histories, philosophies and literatures of diverse ancient cultures. Papyrus libraries were common features of ancient Mediterranean societies with emperors possessing extensive personal scroll libraries.

Strikingly similar to our book culture today, Ancient Rome had booksellers (scriptorium where books were copied by hand), imperial libraries, private libraries and public libraries. The public libraries were located in the baths and served every strata of society. Prior to his assassination, Julius Caesar was planning to construct a gigantic public library.

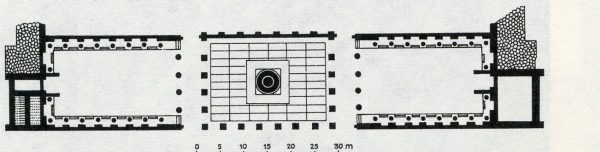

I had the good fortune to be able to visit the site of Trajan’s library located adjacent to his column in central Rome. A friend who is a curator at the National Archeological Museum at Naples arranged for me to meet with the supervising archaeologist at Trajan’s Library. For me, this was an unforgettable personal experience. We descended into a subterranean chamber adjacent to Trajan’s column located beneath the multi lane boulevard constructed by Mussolini adjacent to Trajan’s column. There were delineated areas indicating current investigations. As with other public and imperial libraries, there was evidence that this one consisted of two sections: one for Roman papiri and another for Greek books. Roman admiration for Greek culture extended throughout all strata of society—including a preference for Greek doctors and dentists.

(Feature image: Digital reconstruction of the Villa Dei Papiri seen from the southeast. Courtesy of Museo Archeologico Virtuale di Ercolano)