In 2004, Demos published a pamphlet by Charlie Leadbeater and Paul Miller called Pro Am Revolution. The authors, who define ‘pro-ams’ as amateurs who work to professional standards, write:

The 20th century witnessed the rise of professionals in medicine, science, education, and politics. In one field after another, amateurs and their ramshackle organisations were driven out by people who knew what they were doing and had certificates to prove it.

Leadbeater and Miller argued, however, that this ‘historic shift’ was reversing and that we were witnessing the rise of the pro-am. They called for rethinking the ‘all-or-nothing categories’ of professional and amateur, suggesting instead a spectrum which includes (in the arts, for example) hobbyists at one end, full-time professionals who make their living as artists at the other, and categories in between, including those that would be described best as ‘pro-ams’: people who hold steady day jobs but spend considerable time seriously pursuing an art form (writing, doing fringe theater, sculpting, dancing, playing music, making films, and so on).

As in other fields, the twentieth century saw the rise of the professional nonprofit arts organization and with it professional training programs (and the corresponding disparagement and even displacement of amateur arts organizations and artists). While we may be graduating tens of thousands of students with arts degrees each year, including some percentage billed as ‘professional training’ degrees, as everyone in the arts knows, most of those who train for and aspire to careers as professional artists are unable to support themselves by making art. Indeed, many that call themselves ‘professional artists’ would actually be categorized as ‘pro-ams’ under Leadbeater and Miller’s definition: they may work to professional standards but they’re not making money doing it.

One understands why chronically underemployed artists maintain the professional mantle; if they called themselves part-timers or amateurs they would lose legitimacy with agents, producers, and other gatekeepers, with their peers, and probably in their own eyes, as well. I’m not suggesting that there should be no ‘professional’ category of artist or that artists shouldn’t expect to make a living wage when they work with large professional organizations (see two previous posts here and here for rants on that). However, the ‘professionalized’ ethos of the arts and culture sector in the US seems to be at odds with the difficult reality that most artists (and many administrators) are unable to make anything close to a living in the arts (even when they are working at so-called ‘professional’ nonprofit arts organizations).

Moreover, such an ethos seems out of sync in an era in which amateurs working to professional standards are increasingly embraced as talented and vital contributors across many fields. (Leadbeater and Miller make the point, for instance, that evening and weekend serious stargazers have helped to make important discoveries in astronomy.)

Additionally, there are many more channels available for independent creators to network, make something amazing happen in the world, promote their work, and cultivate a niche or loyal fan base. Meaning, they don’t necessarily need to wait around to be discovered and hired by professional gatekeepers, experts, and intermediaries to have an important and satisfying career in the arts.

As larger forces push institutions toward cooperative infrastructure models and blur the line separating professionals from amateurs it seems that the arts field may be limiting its future (rather than saving it) by continually scrambling to redraw the line and put people on one side or the other of it. Other fields are embracing this shift—witness the open source and crowdsourcing models that are increasingly pursued not only because they often are more efficient, but because they often yield better ideas, contributions, and products.

Despite the fact that a majority of nonprofit arts organizations sustain nothing close to a living wage for anyone working at them, we hold onto the idea of being a ‘professionalized sector’ (with all the jargon, behaviors, goals, practices, and processes that come with that idea) because we perceive that it is meaningful and beneficial (for art, for artists, for the communities we serve) to do so.

But is it? Once you get beyond that relatively small number of institutions that have a sufficient base of support to sustain a full time staff and pay living wages to artists? And if it’s an ideal that has been realized by so few, why is it still held up as an ideal for the entire sector? Especially if, by privileging the idea of professionalism we (perhaps inadvertently) not only discount the vibrant amateur sector, but in a sense, perceive the arts and culture sector to be ‘lacking’ rather than ‘self-actualized’, so to speak? Among the consequences of our fetishism of professional status, it strikes me that we have relegated ourselves to being a sector with huge numbers of unsuccessful and underemployed professional artists rather than a sector with huge numbers of successful, part-time or occasional, pro-am ones.

Perhaps it’s time for the arts and culture sector in the US to embrace its true nature and the possibilities of this new era and rethink what constitutes a ‘satisfying’, ‘successful’, or ‘legitimate’ life/career in the arts in 21st century America?

Re-posted with permission from State of the Artist.

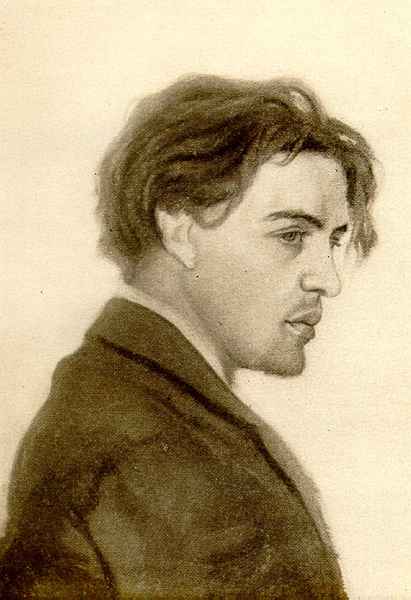

Image: Portrait of Anton Chekhov, professional physician and pro-am writer.