When I saw the poster advertising the Signature Theater production of Samuel D. Hunter’s latest work, I joked to a friend, “This will be about lonely people in Idaho being miserable.” After having seen the show in question, A Case for the Existence of God which has won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play of the 2021-22 season, I realize it was an unfair generalization of a gifted author’s oeuvre. Sort like saying all Tennessee Williams’ plays are about alcoholic neurotics clinging to dreams of a decaying Southland. Case does bare a resemblance to Hunter’s previous works such as Greater Clements, The Whale, Pocatello, and A Bright New Boise. Yes, it does take place in Idaho, there is a conflict over ancestral land, and its two characters are both sad and lonely, but this devastating two-hander has a power all its own.

Credit: Emilio Madrid

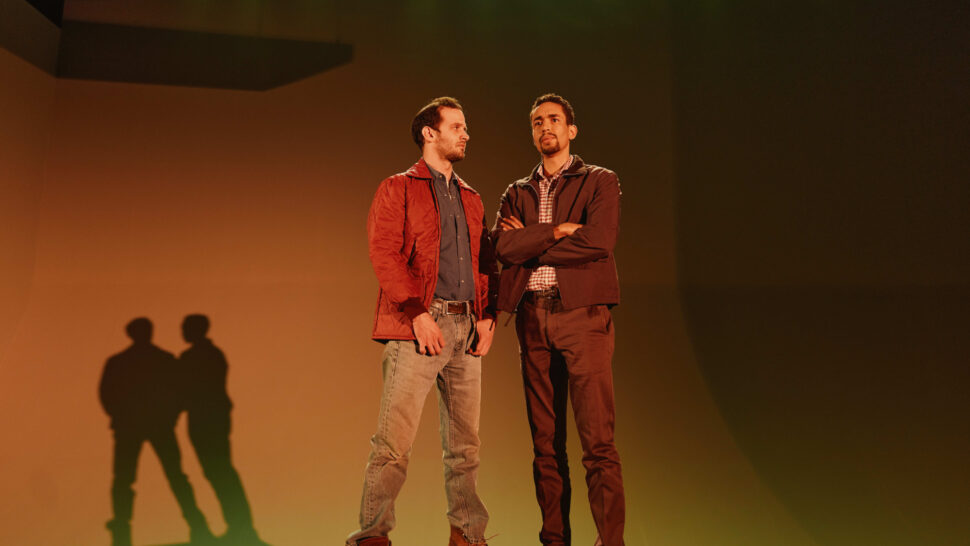

The opening could not be more mundane, yet the plot soon gains momentum with the velocity of a modern Greek tragedy. We are in a tiny office cubicle isolated in the middle of a starkly blank space (Arnulfo Maldonado created the eloquently simple setting.) Ryan (Will Brill), a desperate single dad still recovering from his painful divorce, has come to Keith (Kyle Beltran), a mortgage broker with troubles of his own. Ryan, a shift worker at a yogurt plant, wants to buy twelve acres of land that originally belonged to his family before mental illness and arson caused them to lose it. Keith, who holds degrees in Early Music and English and is now chained to a desk, wants to help because they both have toddler daughters in precarious situations. Ryan’s ex-wife is angling for custody while gay and single Keith is in the process of adopting a foster baby who could be taken from him by the child’s biological aunt.

This common element of potential sorrow connects the two disparate men. Ryan is white, undereducated and scrambling to make a living. Keith is black, gay and from a privileged background. As their friendship grows, they face the horror of a chaotic, dangerous world and a seemingly indifferent deity, though God is never directly mentioned. Ryan pleads that there must be good in the world, but Keith is more cynical. The intense, 90-minute play finishes on an ambiguous note and will leave you shattered.

Credit: Emilio Madrid

Seamlessly directed by David Cromer and compassionately written by Hunter, the trajectory of the two men’s relationship plays like one long conversation with subtle changes in locale and time marked by Tyler Micoleau’s beautifully subtle lighting. Brill and Beltran brilliantly depict the pain and frustration of their characters as well as the fear and anxiety bubbling just below the surface. They also convey the guarded optimism peaking beneath the gloom in the bittersweet ending of this magnificent play.

Credit: Julieta Cervantes

Anchuli Felicia King’s Golden Shield at Manhattan Theater Club’s City Center Off-Broadway space also examines connections and communication, but is complex and plot-heavy while Case is pared down to its bare essence.

A lawsuit against a multinational corporation is the main strand in Shield’s tapestry of a plot, but there are several other threads woven in. A nameless translator (charming and funny Fang Du) acts as our guide on a winding journey across three continents. Attorney Julie Chen (passionate Cindy Cheung) seeks to collect damages against a huge Dallas-based communications company for allegedly collaborating with the Chinese government in harassing, imprisoning and torturing dissidents who attempt to breach the country’s Internet firewall, the “golden shield” of the title.

Credit: Julieta Cervantes

The nature of translation and communication itself becomes the subject as the various players in the suit interact and the narrator offers pointed commentary. The corporation is represented by ruthless Marshall McLaren (Max Gordon Moore in another of his delightfully evil portrayals of villains). His prime objectives are maximizing profit, increasing Internet speed and displaying his vast technical intellect. If someone gets hurt in the process, well, that’s not his problem. Moore gives this hissable antagonist a human side, too. The victims of the Chinese government are heartbreakingly played by Michael C. Liu as Li Dao, the main dissident and Kristin Hung as Huang Mei, his long-suffering wife. (Hung also doubles as brusk government official.) Ironically, Li Dao, like Marshall wants to multiply communication potential, but for the people of Chinese to gain access to the West, not for the government to spread propaganda. For this, he is arrested and crippled.

Eventually, the focus narrows to the fractured relationship between Julie and her wayward sister Eva (complex Rubio Qian), a fluent Mandarin speaker serving as Julie’s translator. The sisters’ troubled childhood and Evie’s sordid past involving drugs and prostitution emerges, indirectly impacting the lawsuit. King wants the siblings’ story to be the center of the play, but Li Dao’s harrowing experience haunt and overshadow their conflict.

In addition, there are storylines with an Australian advocate and the corporation’s shark-like lead attorney (both played with relish by Gillian Saker) as well as Marshall’s sheepish associate and Julie’s pragmatic boss (capable Daniel Jenkins in dual roles). As you can see, there is a lot going in this busy play. King tackles many themes and ideas and manages to make them all clear, with the aide of a proficient cast and May Adrales’ focused direction. There’s plenty to chew on here, but Case is a leaner, more satisfying meal.