Years ago, when I was working at the Los Angeles Times, I wrote a weekly column reporting on whatever hard theatre news came my way. One annual obligation was to report on Broadway’s financial health, based on the official financial statements and growth of its income, year after year.

The truth of the matter — and I provided the numbers to support the point — was that it became obvious over time that the primary reason Broadway’s grosses were steadily climbing was not because producers were turning out bigger and better hits that attracted larger audiences, but because they simply were charging more for tickets to whatever it was that they put on stage. There were occasions when the number of tickets sold had shrunk while the profits increased, just because the public had paid more per ticket. No one disputed those facts.

That manner of calculating things probably has not changed much over the years. It began innocently enough when production costs were indeed rising, as they pretty much tend to do, and producers discovered that the public was mostly undeterred by the higher prices. Cost and effect. What was questionable in the reports was that they made it sound as if the audiences had increased. They had not, not measurably.

Call this market forces if you wish. But this little wrinkle opened the floodgates. It eventually led to that popular development described as “dynamic pricing” that is now widely practiced, even — although for better reasons — by not-for-profit regional theatres. It sounds like a healthy and vigorous way of moving the cost of tickets upwards, but it’s just another euphemism for raising prices when/if theatres discover that they can.

Market forces? Broadly speaking perhaps, but when it comes to commercial theatre the impulse that drove this new movement was both self-defense and less pretty. The practice encompasses not just covering rising costs, which certainly were and continue to be an important part of the reality, but simply making as much money off the product as the show’s popularity allows. In short, as long as they can get away with it.

I understand the temptation to charge more for tickets based on the public’s willingness to pay more taking root in the not-for-profit sector; that not-for-profit qualifier tells you everything you need to know. Not-for-profits struggle. Perpetually. But it does not excuse the more extreme form of the practice in the for-profit commercial theatre — especially Broadway, where experience tells us that, for the many large expensive failures that occur, a major hit will come along that can make obscene amounts of cash long — and I mean loooooong — after it has recouped its investment and made handsome profits. The practice took hold with the huge popularity of Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber’s works, especially his Phantom of the Opera. It continued with Spamalot, rose up with an unvarnished vengeance with The Book of Mormon and reached an epiphany of sorts with Hamilton.

To be fair, the seeds of that movement were already in place. They were just waiting for the right rain to come along and grow them into gold. That came in the form of scalpers. The more gimmicks scalpers could find to buy up as many choice tickets to a hit as possible, that they could resell at astronomical prices, the more it rankled the producers. And rightly so. Eventually, the rationale (and perceived solution) became for the producers to compete with the scalpers by going them one better. They did it essentially by charging similarly stratospheric prices for their tickets at their own box office.

Why let the scalpers have all the fun?

Not only did this decision co-opt an objectionable practice, it also papered it over with palliatives such as ticket “lotteries,” NPR giveaways (a sweetener for purchasing NPR subscriptions) and other gimmicks and prizes. Instead of feeling tricked, an obsessed and eager public was (and is) made to feel lucky for spending countless hours and considerable effort on such stratagems, trying to win or earn an affordable ticket, when it should have felt insulted and humiliated.

Because of Covid-19 and the months of forced closure endured by all theatres, Hamilton has remained the most blatant, though by no means the only assault on our wallets. To be clear, I am not measuring that cost against the quality of Hamilton since I have deliberately not seen it on stage. I have the cast album and have watched the filmed version of the Broadway production on Disney+. These comments are not a review nor any kind of artistic assessment of Hamilton or any other show. My argument is with the grotesque amount of dollars charged for something that remains of totally arbitrary value.

Here’s the reality: the Hamilton edition that was intended to arrive at the Los Angeles Pantages Theatre in the Spring of 2020 was claiming a top box office price, plus a hefty processing fee, somewhere in the neighborhood of $3,300-$3,500 for its prime real estate. (The minimum ticket price at the same performance would have been roughly fifty bucks.) Although the show is now into its sixth year of life, the current top prices being charged in a return run at the same Pantages today — post-album and post-movie — hovered around $600, plus a processing fee of $118. Really? $118 for processing what exactly?

And if you think that’s unconscionable, there’s more. Some preview tickets for the current revival of The Music Man poised to open on Broadway are selling for $600 each. If they’re charging that for a preview to a revival that hasn’t even had a chance to prove itself yet, what will they charge when it opens and if it becomes a hit?

Access to good theatre should never be about abuse. In time abuse becomes its own executioner, and it often comes down to that in our society. It seems plenty is never enough. Money is the god, the fallback, the fallout.

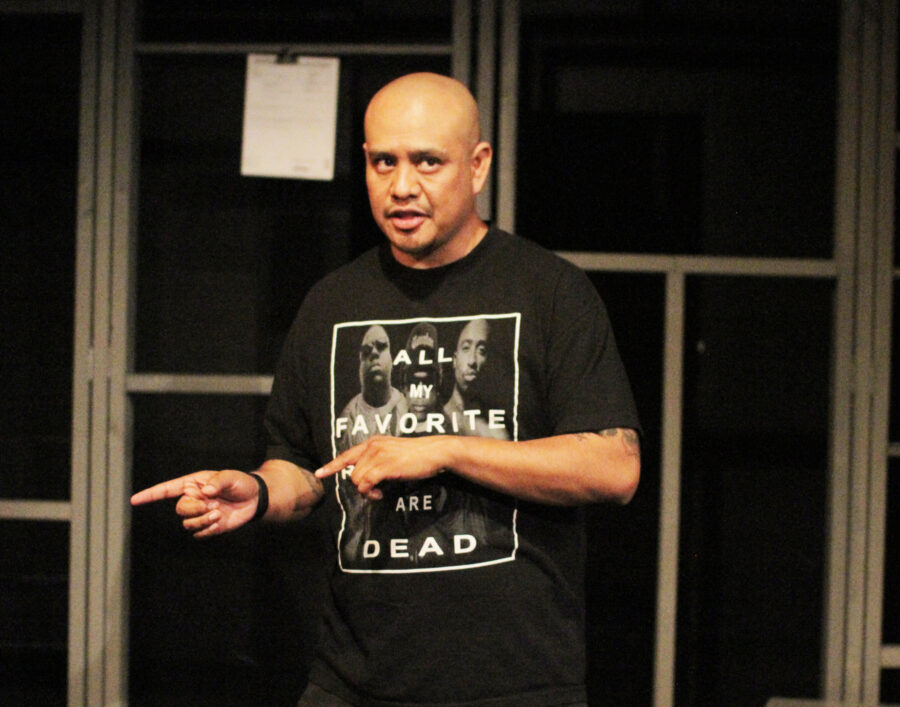

Four years ago, I saw a one-man show called WET, a DACAmented Journey in a 60-seat theatre (give or take), with no set or costume in sight, that was entirely mesmerizing by the singular power of its content, its story and its creator/performer’s talent: what Alex Alpharaoh had to say and how he said it.

Here’s some of what I wrote about it then:

“…Alex Alpharaoh’s autobiographical DACAmented Journey, written and performed by him, is peopled with unforgettable characters, good and bad, conveyed with careful delineation, unfailing humor, great affection, fear, anguish and above all, veracity… While the airwaves daily fill up with the indignities and tribulations suffered by the Dreamer population, nothing makes their plight and their appalling dilemmas as vivid or as eloquent as their telling by this exceptional artist. This is a case in which the particular is not only illuminating, but infinitely more compelling than the universal. Let’s hope they get to film this and show it everywhere in the land, although nothing will be as heartbreaking or heartwarming as seeing the man himself perform it in the flesh.”

Well, it has been filmed since. I hope that this intimate one-man show will reach the much wider audience it deserves. It demands to be seen in every city, on every street corner in this nation, so people can assess how disturbing, distorted and dysfunctional have become our immigration policies. It is a funny, human and touching performance. It stayed with me for weeks and it cost pennies to deliver, comparatively speaking.

(During the pandemic Alpharaoh booked himself a streaming gig through Los Angeles’ Center Theatre Group that I believe helped support the filming of the show. Despite several attempts, I was unable to reach anyone at CTG who could confirm this, but this artist deserves nothing less.)

Let me end on a conciliatory note. Of course not everything that gets on stage can withstand such stark simplicity. Of course money is essential to the big commercial productions that require large casts, many frills, special effects and on and on.

But how much of that is art and how much of it is razzle dazzle? How many times have you attended a show that is to be admired more for its distractions than for what it imparts or how deeply it touches you? And when was the last time a show affected you enough, in whatever manner, to be worth hundreds, if not thousands of dollars a pop?

Theatre was and remains at its core a street art, designed and performed by ordinary people for ordinary people. Its humanistic origins cling to it, even as the form clearly has branched out and evolved hugely in sophistication and technological wizardry. These “big” shows now often are compelled to exhibit all kinds of seductive trickery in their presentation if they are to appeal to their audiences’ ever greater expectations. Yet the theatre’s basic must-haves still remain the three Hs: honesty, humor, humanity.

I don’t believe the first hunter-gatherer who stood up in front of three friends to grunt or mime a story had any idea that she or he had just given birth to theatre, but that is how it all began. And this exceptional and wide-ranging flexibility remains the theatre’s most powerful feature and tool. Among all of the performing arts, theatre is the oldest, the simplest, the most inclusive, the most malleable. It also incorporates many of the other arts, when you consider lighting, costume and set design, to say nothing of music and dance.

There will always be room for the escalating spectacles as well as the smaller stage miracles such as WET. In many ways, the more the merrier is a dictum that applies. Theatre is not and should not be a contest. But the price discrepancies of the megashows, and their endless escalations, have grown to the point where they can only be described as abuse on a monumental scale, when they are perpetuated, to quote Dame Edna “at enormous expense,” so long after their “sell by” date.

Everyone has the choice to purchase or not to purchase any ticket to any show at any price because this is still a free country. What is considered overpricing will inevitably remain a matter of individual perception and subject to one’s discretionary wallet. But there is value and then there is overvalue. It’s your life, your money, your choice — and may what you do with them always be your decision.

(Featured photo by Sylvie Drake)