Art is supposed to remind us our lives matter. Our failures, if we own them, can become our truths. Art is supposed to be a mirror, however distorted.

But too often, in poetry, the lives that matter most become corpses or, worse, dust. I’m talking about the lives most of us — the silent majorities and minorities — lead. I’m talking about lives filled with student loans and kind or heartless bartenders. I mean lives filled with spirit-crushing work and everyday moments of quiet desperation, all those things that often don’t show up in poems at all, as if too tiny to be important.

How sad that is. How lonely it is, when even our poetry has abandoned us. It can lead critics to proclaim, over and over, every five minutes or so, that poetry in America is dead. Capital D.

But don’t flatline just yet.

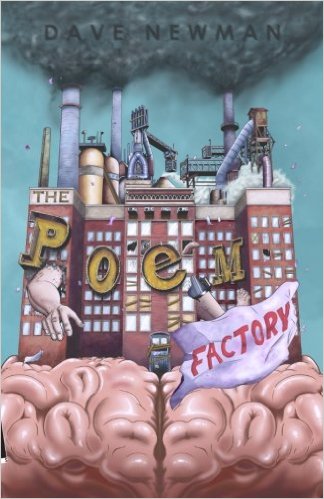

In these generous 173 pages, published this year by White Gorilla Press in New Jersey, there are poems that speak to anyone, except maybe the elite academic poets who might be the ones fueling those rumors of poetry’s demise.

There are poems here about bad jobs, worse jobs, heart-stopping muscle-wrenching, back-shattering jobs. There are poems here about furniture movers and bouncers, strippers and D.U.I.s, about losing religion and finding hope. There are poems about every unexpected and beautiful and struggling heart you might not expect to show up in poems, working-class gay men taking care of dying gay men, women desperate to find lust away from husbands, reflective bartenders on the verge of retirement, and guys willing to stab each other in the heads with forks. And Newman manages all of this in lines as lyrically crafted and precise and true as these from the short poem, “People Who Talk About Being Broke”:

almost never are:

see how they fly across the country

like planes are little ponies

you drop quarters into and ride

and how they manage vacations

more distant than the corner bar.

People who are broke

never talk about being broke.

They’re ashamed.

Class and privilege are central to nearly all the poems in The Poem Factory. One of my favorite short poems addresses a woman who’s critical of a man in front of her in the grocery line who uses food stamps but wears Nikes. Newman writes: “It’s possible that he / like many / intelligent consumers / bought the shoes on sale.”

There is so much compassion and big-heartedness here. And while anger and bewilderment are live-wired through the collection – these poems are as much critique of capitalism and privilege as they are a reflection of our lives within a system built on that – there’s so much humor and delight, too.

Newman writes about sex like Henry Miller might if Henry Miller would have had a better sense of humor about sex. There’s pussy-eating and blow-jobs, unabashed joy, and meanness when people get aggressive and combative.

To people who might be off-put by the direct sexuality in the collection, Newman says: “But let’s face it: / it’s all perverted. / Or: none of it is perverted / when you’re doing it / with the right person.”

Nothing in the world is too small, too perverted or off-limits, too mundane to find its way into a poem and be elevated into song. This is Newman’s credo and it’s one he shares with a lineage that starts with Walt Whitman, who makes some beautiful cameos in this book in poems like “The God in Walt Whitman” (“But you know Walt Whitman now or are remembering him again / and all of us here know we have something good to do so / let’s do it and if that doesn’t work – let’s do it again.”).

The comparisons between Newman and writers like Bukowski come easy, too, though it’s important to note that too many readers overlook Bukowski’s tenderness and fall for the tough-guy-at-the-bar stereotype. Newman’s poems are hard and tender, beautiful and rough, they sing and they stomp – all at once. Bukowski at his best did that, too. Newman’s lineage also would include Bukowski descendents like Gerald Locklin, a West-Coast poet whose clarity and directness and love of the authentic human story Newman shares.

The Poem Factory is a book that fights back against everyone who proclaims American poetry is dead because it has nothing to say to everyday people – the ones who go to jobs that break them down, the ones who budget and scrimp to buy their kids shoes, who long for love but will settle for being seen — you know who I’m talking about because I may be talking about you.

Poetry at its best is supposed to say something honest about what it means to be alive and human on this earth. Dave Newman’s The Poem Factory is that kind of book. Newman quotes Whitman – “I feel I am of them – I belong to those convicts and prostitutes myself, and henceforth I will not deny them – for how can I deny myself?” So The Poem Factory doesn’t deny any of us, especially those of us who have been denied in art for too long. The Poem Factory does what Whitman called everyone to do – it stands up and speaks for others. It is a living, breathing poetry of witness, the best and most unexpected kind.

[alert type=alert-white ]Please consider making a tax-deductible donation now so we can keep publishing strong creative voices.[/alert]