This has been a great year for coming of age pictures to emerge from Sundance, and I think that among them, The Diary of a Teenage Girl is absolutely the best of the bunch. The graphic novel by Phoebe Gloeckner was hailed by Whitney Joiner of Salon.com as “one of the most brutally honest, shocking, tender and beautiful portrayals of growing up female in America,” and her novel has now been so intelligently, sensitively, and imaginatively adapted by first-time helmer Marielle Heller. Under Heller’s assured direction, the story has been rendered in living color by a phenomenally gifted cast and crew. British actress Bel Powley plays the wide-eyed fifteen year old, Minnie Goetze, hungry for sexual experience and drunk with delight in her newfound pleasures and powers. Kristin Wiig, as Charlotte, Minnie’s hip, rebellious, young mom, proves once again that Wiig is not only a premiere comedienne of our time, she is equally a contender in rendering nuanced dramatic material. Alexander Skarsgård, as Monroe, Charlotte’s thirty-two year boyfriend who delights in satisfying the sexual longings of mother and daughter alike, walks a fine line to depict a character whose judgment is so clearly compromised, while remaining such a likeable sleaze-ball (degenerate, pederast) — as implausible as that may sound. With production and costume design that economically evokes San Francisco of the “70s (from Jonah Markowitz and Carmen Grande, respectfully) and animation that so delightfully brings to blossom Minnie’s subjective emotional state and imaginings (courtesy of the Icelandic animator Sara Gunnardottir), the film The Diary of a Teenage Girl is quite a triumph. At its essence, the story recalls an Allen-Farrow-Previn type triangle, narrated without judgment from the point of view of its awakening subject. “It’s not a morality story,” Heller affirms, “This is a rebellion against that.”

“What if you’re a teenage girl who wants to have sex?” Heller probes. It is a question that I think we have been examining more and more directly in film and television over the past decade — from Sex and the City to Girls to Trainwreck. The Diary of a Teenage Girl provides such a fresh and honest portrayal of how young women navigate those rough waters to gain sexual experience, to move from infatuation to self-awareness. Much has been made of the fact that the film needs to be seen by young women who heretofore have had little in the way of truthful depictions of the sexual awakening of adolescent girls in film and art. Honestly, however, I believe that women of all ages will be able to relate to Minnie. In their remembrance of that passage and in their continued attempts to renegotiate their sexuality at every new turn — be that as a single adult, a newly-wed, a married woman in mid-life, a widow, or a divorcé, from innocence, to the height of one’s sexual prowess, through menopause and beyond, there is a fluidity to our sexual experiences that merits such thoughtful consideration.

At the Berlin International Film Festival, The Diary of a Teenage Girl picked up the Grand Prix for Best Feature Film. While nominated for the Jury prize at Sundance, I was disappointed to see that both The Diary of a Teenage Girl and the remarkable and original DOPE were passed over with the award going instead to very fine Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, which nonetheless, recounts a more familiar trope.

Director Marielle Heller and actress Bel Powley were gorgeous to behold, freshly made-up and elegantly attired when I met them in their suite at the San Francisco Fairmont Hotel. They had flown to town for the U.S. premiere of The Diary of a Teenage Girl at the Castro theatre later that night (with party to follow). Their enthusiasm was infectious. The two women enjoyed a loose and breezy intimacy, readily finishing one another’s sentences and spontaneously breaking out into laughter. I had the impression that the collaboration for them had been a celebration of women’s power. Moreover, that we were sitting at the precipice of greatness to come for two remarkable burgeoning artists.

Photo by Sam Emerson, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Sophia Stein: Eight years ago, you discovered this graphic novel – The Diary of a Teenage Girl by Phoebe Gloeckner. Your sister gifted you a copy for Christmas. So I was curious, was this required reading for your sister in high school?

Marielle Heller: No, no, not for school. My sister was a graphic novel fan, and she loved the book. I always relied on her as somebody younger and hipper than me to keep me up on culturally relevant things. She’s six years younger than me and technically a different generation — because I was born in ’79 and she was born in ’85.

She gave The Diary of a Teenage Girl to me and said, “I loved this book. This means so much to me.” And the moment I read it, I was so taken by it. (It feels as if I have made up this next part for publicity, but it’s what actually transpired.) I closed the cover of the book, looked on the back, Googled the name of the publisher, phoned them and said, “I want to adapt this book.” I was just pacing in my apartment, rambling on about how much I loved it, and how I wanted to adapt it into a play. Somehow they didn’t hang up on me. Eventually they connected me with author Phoebe Gloeckner.

Sophia: What was it about the work that inspired that degree of excitement in you?

Marielle: I had never previously come across anything whatsoever that had an authentic depiction of a teenage girl. I realized that without having honest depictions of what it feels like to be a teenage girl, I had come of age feeling as though something was wrong with me. I felt like I was a freak. If you are a boy, there are all of these examples of how anything you might think of when it comes to sex is normal. If you are thinking about having sex with your cousin, if you want to have sex with a pie, if you want to masturbate in bluh-bluh-bluh – there are all of these examples for boys, that reinforce the notion: “Trust me, you’re probably normal.”

For girls, the lesson we’re given is: You’re not going to want to have sex. Eventually, boys are going to pressure you, and when you decide the time is right, you’re going to have to give in. But you guard your virginity with your life. No one ever says what happens if you want to have sex before the boys want to have sex. What if you mature before the boys do? – which is what usually happens.

Bel Powley: It is what happens more often.

Marielle: Girls are much more mature. I remember my first high school boyfriend being just terrified of me and what I wanted to do sexually.

Bel: Like Ricky Wasserman. [Minnie’s high school love interest, played in the film by Austin Lyon.]

Marielle: Exactly.

Photo by Sam Emerson, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Sophia: Over the weekend, I told a friend how much I loved this movie and that I was going to speak with you both. Then I pitched her the premise: “A teenage girl has an affair with her mother’s boyfriend,” and I found myself qualifying the description, adding, “but it’s not icky, you know.” Which prompted her to confess that she had lost her virginity during high school at the age of fourteen to a thirty-two year old man – which, in hindsight, she realizes, was inappropriate. But at the time, she could not really comprehend just how inappropriate it was.

Marielle: Right. That’s the thing: When you are going through whatever you are going through as a teenager, you don’t feel like anything you are doing is dangerous or wrong. You feel like it’s exhilarating. And sometimes really painful – because you’re dramatic and everything is a matter of life or death. But you don’t have this feeling of moralizing what’s happening to you, as it is happening. If anything, you’re probably having a good time and learning about yourself. You’re getting hurt at times, but you’re experiencing things really fully. You feel like you’re in control. You feel like you’re making decisions. You feel like you’re an adult. That’s how I felt as a teenage girl.

The film tells the story from that perspective. It is not moralizing. It is not judging. It’s only based on how Minnie feels in every moment. If she doesn’t feel like a victim, we can’t feel like she’s a victim. At the moment where she suddenly starts to turn on Monroe and see him as something different, that’s when we as an audience start to see him as something negative.

Bel: She starts the relationship. Minnie comes onto him.

Marielle: Full on agency. Minnie believes –

Bel: Minnie decides, I’m going to have sex with this person. And she says, “I want you to fuck me.” I feel like that’s a moment that we all have as young teenagers. — Where you’re like: O.K., now I’m ready to enter into this sexual journey, I’m gonna do it. I’m ready to be an adult! And whoever it is, you’re like, “I want you to fuck me.”

Marielle: Yeah! This is a movie about female sexuality, about coming into your own sexually. We talk a lot about how empowering it is to see a woman exploring her sexuality without shame. The flipside of this particular story is that it is an older man who is taking advantage of the situation. There is no doubt that this man, Monroe, is abusing a situation that exists — in large part, because he himself is like a big kid. He doesn’t think of himself as a grown-up. He thinks of himself as somebody who is, probably, emotionally the equivalent age of Minnie. Plus it’s the “70s, so the rules have been thrown out. The idea of who’s a grown-up and who is not has already been totally flipped on its head. Monroe is pretty confused about his own responsibility. He doesn’t take responsibility for anything in his life. Minnie’s not a victim, and Monroe is not a predator. Neither of these characters are black-and-white, and it’s not a black-and-white situation.

Photo by Sam Emerson, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Sophia: Casting Alexander Skarsgård as Monroe was a brilliant choice. What was it about Skarsgård that led you to trust that he would do justice to this role?

Marielle: I knew that I needed somebody to do this part who had major chops. He had to be a really deep actor. I had seen Alex on True Blood, where he plays this sexpot vampire — that’s not a role that I would ever equate with this part. Then, when I watched him in What Maisie Knew, with Julianne Moore, I realized he really had that depth. He just felt like this nuanced, gentle giant. I felt like suddenly I saw him.

Alex came to the process of making this film with so much humanity for the character of Monroe. He was able to really see the nuance in this guy and to not judge him – which was crucial, because, I think, a lot of actors, would have come in with judgment.

Sophia: Bel, You had to build this intimacy with this actor that you had never met before. How did you approach working with him to build up that relationship?

Bel: We had about two weeks of rehearsal before we started shooting. We kind of just sat round the table and talked about Minnie and Monroe. We went through the script chronologically and mapped out the emotional journey of their relationship. — So that we always knew at each point where we were coming from, where we were going, and exactly how our characters felt in those moments. During those two weeks of rehearsal, it was really collaborative. If there was something that didn’t feel right, if we wanted to discuss a certain bit of blocking, or if a line felt like it needed to be flipped on its head or something, we would all discuss it. Mari was so amazing. We would go away and write stuff, and we’d get on our feet and walk around and just kind of work things through. So that when we got on set, we had this strong base for the relationship, and we could find new things. I think that’s really important.

I know that I’ve learnt that from doing theatre — and Mari, you’ve learnt from doing theatre — if you have that rehearsal process, then you know exactly where you are in your heart as your character at each point. That then opens you up to a whole world of new feelings that you’ll find when you’re on set.

Marielle: It’s true. In some way, doing more work and more prep, actually gives you more freedom because you’re able to just let go a little bit and trust your instincts.

Bel: Because you can settle into who you are.

Photo by Sam Emerson, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Sophia: You both come from theatre backgrounds. — But theatre in different countries: the United States [for Marielle] and Great Britain [for Bel].

Marielle: Although I’ve done a play in England —

Bel: And I’ve done a play in New York.

Sophia: So how did that translate in terms of finding a common language for working together?

Marielle: Coming from theatre, loving rehearsal and character work, I think that Bel and I automatically shared a common language. Even though Alex doesn’t come from theatre, maybe him being Swedish — he also loved the rehearsal process and being able to really dive deep into the characters and all of their nuances.

I’ve never made another movie, but I think, sometimes on other movies, the actors learn their lines the day before, they come in and it’s sort of like, “Okay, what’s this scene about?” You start out the day trying to figure out what that scene is about. But that wasn’t our process at all. We knew these characters in a really deep way before the first camera started rolling.

Sophia: Marielle, you knew the character, Minnie, not only from having adapted the book into a screenplay, you had also played Minnie in the off-Broadway production of the play you had adapted. At what point in the process did you make the determination that you were not going to play the role in the film? That you would cast an actress to play the role that you had debuted?

Marielle: I was never going to play the role on film. I’m thirty-five, and I can get away with things on stage that I could never get away with in film. But also, this was my foray into directing, and I was taking that really seriously. Directing is frickin’ hard. It is all-encompassing. If I had had to be trying to act on top of that, I just never would have been able to really do the proper job that I needed to do as a director. I really respect actors who are able to direct themselves, like Lena Dunham. I’d love to try at some point, but for my first film, and such an ambitious film, I just thought, there is no way.

Photo by Sam Emerson, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Sophia: You discovered Bel Powley on tape.

Marielle: (completely deadpan) I did. She was scrubbing toilets when I found her.

[Enormous laughter.]

There’s this feeling that I discovered her, but she was a very accomplished theatre actress. She had been on Broadway, she was on a T.V. show in England, but to Americans, I discovered her. And I’m going to take credit for that forever!

Bel: I like that.

Marielle: I found Bel when she was just a little baby, and I raised her.

Sophia: Bel, your performance as Minnie is riveting. How did you prepare to play the role?

Bel: When I read the script, I related to the character so implicitly. As a teenager, I was just like Minnie. We always point out, “You don’t need to have slept with your mom’s boyfriend to relate to Minnie.” It’s just the way that she is. Her emotions are so on the surface. And her heart feels like it is going to explode out of her chest! She oscillates between so many different emotions at one time. She really confuses sex and love. Monroe touches her tit, and she becomes obsessed with him. I related to that extremity of emotion so much. So it was really just tapping back into how I was when I was a teenager. I was fifteen — eight years ago.

Marielle: You were fifteen, six years before we filmed.

Bel: Exactly. And it was just like that.

But once I tried to tap back into being a teenager, I found that it is actually more difficult than I was expecting. The way you hold yourself, the way you speak, that crazy way of thinking when you’re a teenager is so specific to being a teenager. It must be something to do with hormones or something because now that I’m an adult, I feel like I’m so much more fashioned and mature.

Marielle: We would both check in with each other: “Is this how you felt when you were a teenager?” “I remember lying in bed and thinking this …” “Yeah, that’s how I did it, but it was more like this.” We would use each other as a litmus test: “Does this feel authentic?” Because that was always the goal. How do we tell the most authentic version of this story? And what did we really feel when we were that age?

Photo by Sam Emerson, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Sophia: The character, Minnie, is an artist who idealizes Aline Kominsky and her “Twisted Sister” comics —

Marielle: At the time the movie takes place, Kominsky was living with R. Crumb, whom she married. But Kominsky was in her own right such a revolutionary of the underground comic book movement of the “70s. At that time, it was a largely male-dominated industry. Kominsky was drawing these really self-deprecating cartoons. She has this one that we used in the movie of herself sitting on a toilet, looking at herself in the mirror, and in the mirror, she looks grotesque. It is a consideration of the question: “What do women see when they look at themselves?” First of all, just depicting a woman sitting on the toilet was a revolutionary thing to do. Then also to see her reflection of herself in that way, when feminism was on the rise, it was not so P.C. to be talking about not loving yourself, in that way. Kominsky was really cutting edge. Her style of drawing is crude, and beautiful, and human.

Sophia: You had some remarkable directorial mentors at Sundance — Lisa Cholodenko (The Kids Are All Right, High Art, Laurel Canyon) and Nicole Holofcener (Enough Said, Friends with Money, Please Give). What were some specifics they imparted to you about directing?

Marielle: The biggest thing that I took away from my whole time at Sundance and all of those people was to trust what I know about the story and to not settle in any moment for not having it be exactly the way I wanted it to be. So if I saw anything in the frame that wasn’t exactly what I wanted it to look like, to not go on until I had it the way I wanted it. To be able to communicate your vision to all the collaborators that you’re working with — your actors, but also your cinematographer and your design people. To be able to take your story that you know so well inside your brain and to be able to communicate that to the outside world.

To trust yourself. Trust that you know the story. You are the guardian of this story, and you need to move forward just guarding it with your life.

“Diary of a Teenage Girl” at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco. Photo courtesy of Tommy Lau.

Sophia: I think that it is really marvelous and interesting that you won the Grand Prix in Berlin for Best First Feature for “the uncompromising rejection of conventional morality in favor of human complexity.”

Bel: Oh —

Marielle: I love that.

Bel: I’ve never heard that.

Marielle: I must have heard it, but that just gave me chills.

Sophia: Do you think that your story will be perceived differently across different generations of viewers?

Marielle: Well, I think right now at this moment in time, part of the story of this film is that people are suddenly interested in female filmmakers and what it is to be a female filmmaker. I love being part of that conversation. I want to talk about that all the time. But I hope that in future generations, I’ll just be thought of as a director, and nobody will have to talk about the fact that I was a woman and how rare that was. — That only 9% of movies were being directed by women at the time. I think we have to have that conversation in order for things to change. But I hope in the future, it will be: “Wasn’t this a great movie!”

Photo by Sam Emerson, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

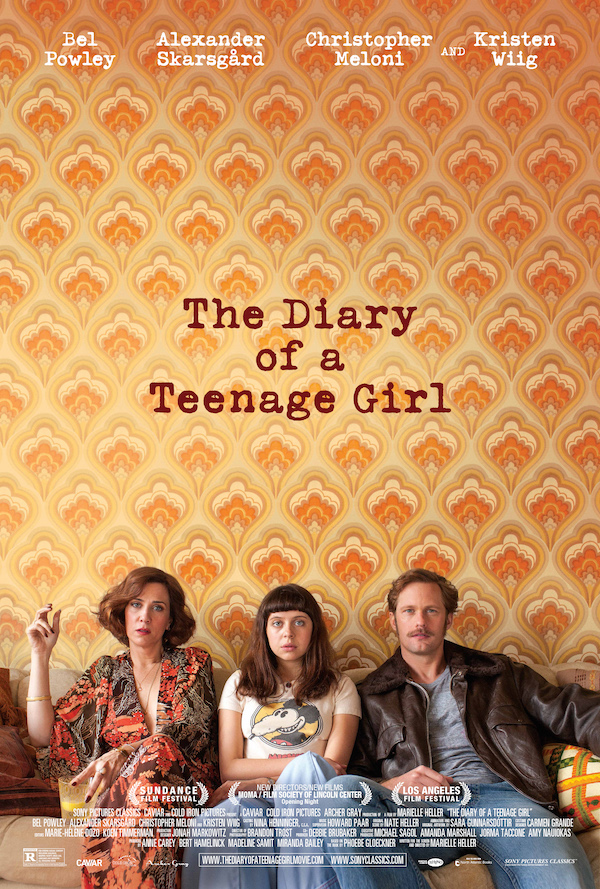

Top Image: Bel Powley (Minnie), “Diary of a Teenage Girl.” Photo by Sam Emerson, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.