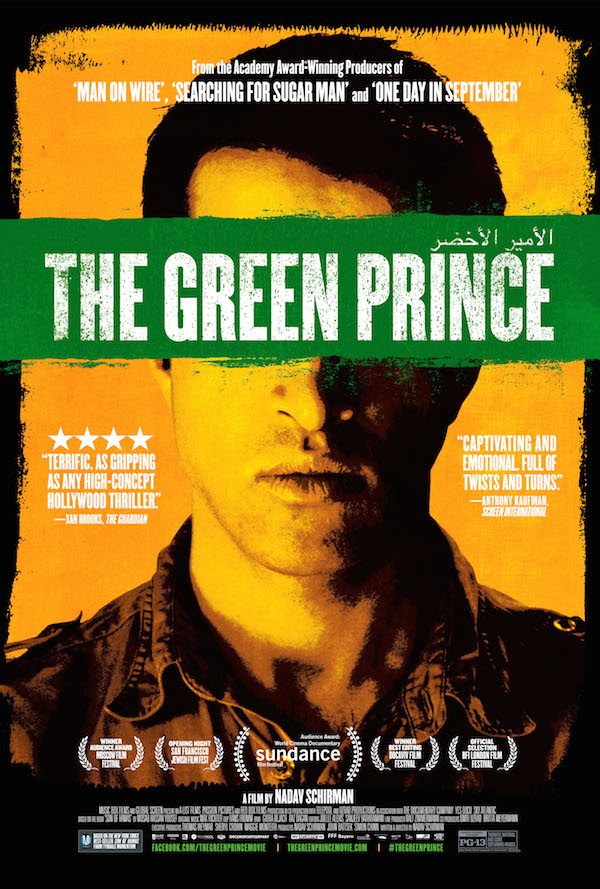

The Green Prince from Israeli director, Nadav Schirman, is the real-life documentary thriller that unveils the relationship between Mosab Hassan Yousef, the eldest son of a top Hamas leader, and Gonen Ben Yitzak, his true-life Shin Bet handler. The film premiered on opening night of the 2014 Sundance Film Festival, where it received the Audience Award in the World Documentary Competition. At last, you will have an opportunity to see this inspiring, not-to-be-missed film in theatres and on-demand.

Born and raised as a Muslim extremist “to hate and kill all Jews” (Mosab’s own words), Mosab was being groomed as his father’s successor. He was recruited as a teenager to spy on his own people under the code name of “The Green Prince,” and he described his experience as a collaborator with the Israeli government for over ten years in his memoir, Son of Hamas. As a captive in an Israeli prison, Mosab saw first-hand the randomness of torture perpetuated by Hamas prison leaders, and he began to question his allegiances. He came to fear that “cowards in the name of courage, were leading an entire nation to death.”

In recruiting Mosab, Gonen explains, “It was as if we were recruiting the son of the Prime Minister … He was not just a source, he was there for us all the time.” Their unlikely partnership led to the arrest of top terrorist masterminds, prevented multiple suicide bombings, and uncovered critical secrets. For both men, loyalty to personal conscience would come to supersede all other competing loyalties — be these political, professional, or personal. Most surprisingly, having endured such a crucible, their commitment to one another became forged as strong as steel. The stunning documentary, The Green Prince, uses an exceptional case to hint at the possibility for deep reconciliation. As difficult as it may be for people to imagine such friendship and loyalty between a Palestinian Muslim and an Israeli Jew, the power of The Green Prince is that it gives face to just this possibility.

I was honored to speak with true-life heroes Mosab Hassan Yousef and Gonen Ben Yitzak, along with director Nadav Schirman, when they were all in town recently for the screening of The Green Prince on opening night of the San Francisco International Jewish Film Festival.

Sophia: Gonen, what was the significance of the code name that the Shin Bet used for Mosab, “The Green Prince”? What does that mean?

Gonen Ben Yitzhak: Prince — because Mosab came from a royal Hamas family. His father is one of the founders of Hamas. Green is the color of Islam. So it was just obvious that he would be “The Green Prince.”

Mosab Hassan Yousef: Have you ever heard of “the green danger”? The United States categorizes its enemies as the “red” danger (for the Communists). The “green” danger is danger from political instruments. It’s a universal, I think, the green color. It’s not only used by Israelis.

Sophia: We typically associate the color green with the environmental movement here in the United States. I did not realize this alternate connotation. Mosab, how old were you when you were recruited by the Shin Bet?’

Mosab: I was arrested right after my eighteenth birthday and spent about sixteen months in prison, which is when I agreed to work for the agency. I started practically working for the agency around the age of twenty after I was released from prison, but they did not give me any official missions until around the age of twenty-one.

Sophia: You made a radical transformation in your life from wanting to kill Israelis to make them feel the pain of your people, to taking many risks to save their lives.

Mosab: Not only their lives. Many Palestinian lives were saved, as well. When we stopped a suicide bomber, first of all we stopped that person from committing suicide. Because of the intelligence and the knowledge of the dynamics of the terrorist organizations that we had, that gave us the advantage — the luxury, you could say – in the Ramallah area to avoid any operation that would have cost civilian causalities.

Sophia: How many lives do you estimate that you saved collaborating together?

Gonen: We never, never tried to do this calculation.

Mosab: We can’t. It’s about principle. It’s not about if it was fifty or a hundred. Sometimes you save the life of an animal, and that calibrates highly on the conscience.

Sophia: Gonen, you have said of Mosab: “He was not just a source, he was there for us all the time.” In what ways?

Gonen: The Second Intifada was very brutal; we faced so many terror attacks. It was a feeling that you need someone to trust from the other side, the Palestinian side. I found myself as the manager of the Ramallah district at that time sometimes arriving at a dead end. We would get a piece of information, we would know that there was a terror attack that was going to be committed, yet we had no tools to stop it. The agency and the state of Israel waited for me to give an answer for how to stop it — this is why I got paid. When I would reach this dead end, usually, I would call Mosab, The Green Prince. “Listen, this is the situation. What can we do?,” I would ask him. I don’t think that there was ever a time when Mosab answered, “I don’t know.” Mosab always had a very smart solution to the situation. Sometimes we achieved things that if you showed them in a movie, you would say, “This is a very cheesy movie. It can’t work this way!!” Mosab had an extraordinary ability to think from an intelligence point of view to evaluate the situation and understand where he needed to be in order to stop the terror attack.

So actually the most important “handler” (I would use that word to describe Mosab) — was Mosab. I supervised a number of Israeli handlers in my district, and Mosab was the most important one because he always knew how to find the solution.

We had a suicide bomber coming from Nablus. We knew nothing about him. We knew that he wears a certain kind of shirt, that’s it. Mosab found a way, and we arrested him before he committed a suicide attack. This is when I understood that Mosab wasn’t just a source that was working for us; he was a very important member of our team.

Mosab: Thank you, Gonen.

Gonen: Thank you.

Sophia: Mosab, you went from contemplating killing your Shin Bet handler, to claiming: “He is my brother, I would not hesitate to sacrifice my own life to save his.” At what point did you start feeling that way?

Mosab: This was an evolution. It did not happen at the beginning.

If you go out to the streets of Gaza, and you ask a ten year old kid, “If you get the opportunity to kill an Israeli, will you do it?” His answer is going to be “yes.” We grew up in a very, very brutal environment — with poverty and violence to the level that we didn’t have anything to lose.

So now, when your enemy arrests you and beats you almost to death, and comes around to say, “Hey, would you like to work for us?” It’s a way to escape, a way to take revenge, you think. (But this is very naïve thinking, if you know what I mean.)

Later on, I started to see the reality of the agency, and the reality on the ground through their eyes. They could not, you know, just keep me in the dark. They had to inform me, educate me. They asked me to go to school, to read things. They discussed many things with me — not to brainwash me, but to open my eyes to different possibilities. This is when I started to see a different truth.

… I was not sure. It took years to keep evolving and growing. Then, killing in principle became a forbidden thing. I knew that if I killed anybody, how could I wash that away? How could I undo that? There is no way to undo it. Killing for what? For a political position? A political idea? A religious idea? At that time, I was questioning all my political and religious ideas, and their truths actually became falsehood to me. So, the motive to kill was gone.

It was a slow journey of transformation. It’s not that I was bad and became good. I was uninformed, unaware, ignorant, living in the dark, and then I started to evolve and see a bigger picture.

Sophia: What was your original motivation for writing the memoir?

Mosab: The truth that I had witnessed was from a very unique angle. I was part of one of the deadliest and most secretive terrorist organizations. It’s own members don’t know about it. I knew Hamas before it was established, and I had witnessed its evolution.

On the other side, when I worked for the Israeli intelligence, I witnessed the dynamics of one of the most powerful intelligence services in the world. I started to see truth and distorted truth. I saw what was on the news, and I knew exactly what was happening on the ground, in the concrete reality.

For ten years, media was coming to our house on a daily basis to interview my father. I started to understand the level of delusion that he was living in. I started to see the connection between this delusion and the bloodshed. How many times I came to a scene where I saw children torn apart! Those pictures cannot leave. It’s not that I’m living a nightmare, but I’m aware of exactly what happens. Now when this illusion about whatever theories that my father and his cohorts had created to cover up their dirty business basically came to light, I felt that somebody had to step in and say something.

I realized the danger. I always knew that I had to document my life on paper – not to publish it, just to document it in case anything happened to me. So this is how I started the process of writing.

While in the process of writing, Hamas took over Gaza and I witnessed Hamas people throwing their Fatah rivals alive from the twentieth floor skyscrapers — Palestinian vs. Palestinian. When I saw that, basically, I decided to go out and tell my truth and to challenge all parties with it. I worked with a ghostwriter, and the whole process took about a year and a half.

Sophia: When you were writing the memoir, did you imagine from the beginning that it might become a film?

Mosab: I was arrested several times for the sake of cover, and I remember the way the Israeli soldiers mocked me as a terrorist. One time, I was smuggling in a chip to communicate with the agency. I put the chip somewhere inside the leather lining of my wallet, so that nothing showed, when this female soldier insisted on taking the wallet away. “I don’t understand, this is a very important gift for me for the memories of my loved ones, please don’t take it,” I pleaded with her. She took it away forcefully to punish me, I suppose, not realizing that she was cutting off my connection with the Shin Bet. Basically, at that moment, I teared-up imagining, what if one day she were to see this scene in a film. How is she going to feel about that? I felt proud to think that she would be crying. I thought, if there is a chance for someone to tell this story, it’s going to be written into a movie, but first I’ll probably die. I didn’t know that this movie would be made in my lifetime.

Sophia: Gonen, your brother-in-law was a co-producer of the project. How did you and he come to be involved in the film?

Gonen: Maybe a year after Mosab moved from the West Bank to the U.S., there was an article in Haaretz newspaper telling the story of the son of a Hamas leader that converted to Christianity and had moved to the U.S. Now, I was shocked to read this because nobody knew about him. Also, at that time, Avi Issacharoff, the guy that wrote the article, didn’t know that Mosab was working for the Shin Bet, and that actually, Mosab had been maybe the most important intelligence asset of Israel.

At that time, I was no longer at the Shin Bet. I didn’t know what had happened; however, I knew that if Mosab was in the U.S., something very dramatic must have happened. When I read the article, I understood that Mosab was in a very bad condition alone in the U.S., and I said I can’t let him just deal with this himself.

I emailed Issacharoff that I had been very touched by the story, and I wanted to help out this guy. I didn’t tell him that I had been his handler, or that I had worked for the Shin Bet. Very surprisingly, Issacharoff sent me Mosab’s email.

Now, I needed to decide, am I going to send Mosab an email? I thought, probably, the Shin Bet is monitoring his email, so they’ll know immediately that I’m trying to contact him. I didn’t want to ask their permission – cause even when I worked at the Shin Bet, I didn’t ask for permissions, so I wasn’t going to do that after leaving the agency. But I was a law student at that time, and I knew that this might be problematic. I knew that they could argue that I had contacted perhaps “an enemy agent” — you never know with an intelligence agency how they will react to these kind of things. Nevertheless, I decided to send Mosab an email.

Then, I had another problem. Mosab didn’t know if I was still in the agency or not? If I sent him an email, maybe he would think that this is the way that the agency is trying to get him back. So, in order to deal with that, I decided to reveal my real identity to Mosab for the first time. When we were working together at the agency, Mosab only knew my nickname. He didn’t know who I was, where I lived, what I did; except that I worked as a handler, he knew nothing about me. The first time he learned who I was, was in that email. I wrote him my real name, where I lived, the names of my children, what I did, where I was studying. A few months later, I went to the U.S. for the first time to meet him. Then a few years later, I went to court as a witness on his behalf [in his suit for emigration].

Mosab told me at that first meeting in San Diego, “I’m going to write a book.” Of course, I encouraged him, but I advised him, “Listen, don’t put yourself in a place where you fight the agency. Don’t reveal too many secrets.” “Tell your story,” I told him, “but I cannot be a part of it.” I didn’t think about movies, I didn’t think about anything.

The book was published a year or so later. Of course, it was very successful. [A New York Times Bestseller]. My brother-in-law read the book and learned about my relationship with Mosab, and my brother-in-law suggested doing something with the book. He contacted Nadav and Mosab. I wasn’t sure I wanted to do it. But I just went with it, and now, the rest is history.

Sophia: So the first time you both saw the film, were you alone? Were you in an audience? What do you remember about seeing it for the first time?

Mosab: I saw it for the first time at Sundance, in an audience. I went to watch a movie about myself. Of course, I’d been part of this process, giving the interviews and everything. I didn’t know what it was going to be like. I didn’t know where Nadav was going to take the movie. From the beginning, however, I was confident that Nadav would take it to the right place.

It’s not easy to watch it. I see my face — my big face, on a bigger screen, talking a language which is not my mother tongue — it’s not easy. Sometimes I think, Why did I say this? Why didn’t I say that in a different way? But I was very happy with the outcome. Not because I think that the film flatters me or Mosab, but because I think that Nadav realized the story the way that I had wanted.

Sophia: How about you Mosab, what was your reaction to seeing the film for the first time?

Mosab: Knowing that it’s impossible to encapsulate my life in a film, I prepared myself not to be attached to it. Knowing that Nadav would do an amazing job because he understood the story very well, but understanding that he is limited by the constraints of time for a feature film.

At the end of the day, it’s not who I am. It’s part of me. It’s my persona on the big screen. If I believe that this is who I am and that’s it, I think that would be a problem. But if I look at myself in the film as a reflection of who I was at some point, it’s amazing. I love the film.

Nadav: Hopefully, you’ve changed a lot in the process of filming it. I remember, when we shot the first time, August, three years ago, and then we shot a year later and you had changed so much already — in your self-awareness, in your demeanor, you know what I mean?

Mosab: True.

Nadav: And now again, you have evolved. I’m sure it’s difficult when you keep evolving consciously, to look at yourself.

Sophia: What has the reception from Israeli audiences been like to the film?

Nadav: We opened in Docaviv before it went out into theatres. I remember feeling quite nervous because this was home turf. How would people respond to Gonen speaking in English? How would people take the story? The lights came on, Mosab and Gonen came up on stage, and it was something which I have never seen in Israel. People got up on their feet, and there was this sort of spontaneous standing ovation at every screening which would last for seven or eight minutes. This never happens in Israel. Israelis are a pretty cynical people. Yet, you felt that the movie was drawing something out of them. Audiences were filled with people from the right-wing and the left-wing, polar opposites who seemed united in their appreciation for the film. Every person saw something very different in it. It has been very inspiring.

Sophia: Will Palestinians in the territories have an opportunity to see the film?

Nadav: God willing. You know, god willing. It’s a challenging thing. I hope so because we made this film for everybody. Like Mosab often describes, his journey was a coming out of darkness — an opening, an expanding of horizons. Hopefully, if others get a chance to see this story, they too may be inspired.

Sophia: Mosab, you sought political asylum in the U.S. How did you chose the United States to be your new home?

[very extended pause]

Mosab: [incredulous] How did I choose the U.S.?

Sophia: Yes, out of all the places in the world, why were you attracted to the United States?

Mosab: I think everybody is attracted to the United States.

[Gonen and Sophia share a huge laugh.]

Mosab: First of all, I had friends here in the United States. Second, my original plan was to study in the United States. Third, safety-wise, freedom-wise, there are many reasons.

Sophia: What are the things that you most appreciate about life in the United States, and what are the things that you find most challenging about life in the United States?

Mosab: In the United States of America, what’s really fascinating to me is the amount of freedom that we have. And liberty. Of course, protected by a solid constitution. I like the example of a smaller government, and I like the equal opportunity for everybody. Human rights and the American generosity, the higher conscience. I say this without a doubt, the American conscience calibrates higher among all other countries. Yes, there are things that we can criticize. In general, I prefer the American model. I think it gives the human conscience much more space to evolve.

Sophia: Nadav, you were born in Israel, and you even served in the Israeli military, but today you live in Germany. Why did you make that choice?

Nadav: My dad was an Israeli diplomat so I grew up pretty much all over the world. When I was of the age that I could choose where to live for myself, I chose to leave a lot of opportunities here in the United States. I was in a very good college, but I went back to Israel to do my military service and stayed in Israel for a very long time. Then I went to Germany to work on my second film. One thing led to another, and I stayed there. I am now based in Frankfort, but I’m between Frankfort and Tel Aviv, all the time. It’s a very small distance. It’s shorter than going from L.A. to New York. With the ease of travel today, you can be in many places.

Sophia: I have been reading a lot in the papers about mounting anti-Semitism in Europe. Is that a part of your awareness? What is the present day climate like for Jews in Germany?

Nadav: This whole war has been fueling a lot of emotions, not only in Europe, but all over the globe recently. In Europe, people have the freedom to demonstrate, but it’s being abused these days. Citizens are asking for permission to do anti-War demonstrations, and these turn into full-blown anti-Semitic demonstrations. In Germany, there are laws against anti-Semitism. So I hope that the authorities are going to be observing these laws. In France, the authorities are afraid to control the anti-Semitic demagogues because of the threat of a backlash that might result in more riots.

Sophia: My father talks about how in the aftermath of WWII during his childhood, the intolerance for Germans and Japanese in this country was so pronounced that he could never have imagined the relationship that the US today has with these two countries, their peoples and their cultures. I am wondering how you each feel. Do you think that in our lifetimes that we will experience the deep reconciliation between the Palestinian people and Jewish people in the Middle East about which we are dreaming?

Gonen: I think that it would be a bit naïve to think that this will happen fast. I do believe that Palestinians and Jews will learn along the way that they cannot ignore the fact that we live in the same region, and we need to find a way to live together.

You know, my oldest son is ten years. When he was at a friend’s house recently, he experienced a missile attack above his head. He came back home and said, “We need to kill all the Palestinians.” — And he loves Mosab. He knows that Mosab is Palestinian. He loves Mosab, and he admires him. “You know, Alon, during the Second Intifada, when I was working in Ramallah, many times, I faced all kinds of terror attacks,” I told him, “and sometimes I felt like you did. But then when you think about it, the way that Hamas is attacking us today, trying to kill innocent people like you, we cannot do the same.”

I have hope and do believe that we will find a way. It’s not going to be easy. It’s not going to happen tomorrow. But we will find a way to live together because we have no other choice.

Nadav: To provide a sense of perspective: you know the Protestants and the Catholics were killing each other for 400 years in Europe. This Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been going on for 60 years. It’s going to resolve itself, you know. Here in the United States, the South and the North were fighting brother against brother. The Palestinians and the Israelis are very close. They are both very passionate peoples.

For me, as a filmmaker, this film is my two cents. These two gentlemen, Gonen and Mosab, took a tremendous risk to trust one another, and in doing so, they inspired us. So if we take the risk to trust the other side and the other side takes the risk to trust us, maybe it’s going to be one step towards resolving this.

Sophia: One of the most powerful stories in the film, speaks to Hamas and The Shin Bet as sometimes obstacles to peace. Mosab talks about how he brought foreigners to meet with his father to explore alternative ways of fighting the occupation. His father shared these ideas with the leadership in Gaza, and they didn’t know where he was coming from. Likewise, the Shin Bet didn’t appreciate that development because they wanted Mosab to act like a zealot, to infiltrate terrorism by “playing” a terrorist and not a peacemaker. What do you make of Hamas and the Shin Bet as obstacles to peace or possible conduits to peace?

Mosab: It’s the wrong comparison.

Gonen: That’s what I feel. To put them together.

Mosab: Look, each party is serving their own agendas. The Israeli intelligence agenda does not represent only the Israeli agenda. The Israeli intelligence serves a democratic country that has Arabs, Muslims, and Christians in it. Hamas does the opposite of the Shin Bet. Hamas takes their own children and puts them in front of the canon of a tank that they hide behind. Hamas has been a real obstacle in the way.

But this is not what I care about — Hamas and Israeli intelligence. I would like for the average person on both sides to be more informed and to be able to think for themselves — to put pressure on all sides. As long as the person is fighting for the carrot they see, and they don’t see any farther, we’re going to continue killing each other.

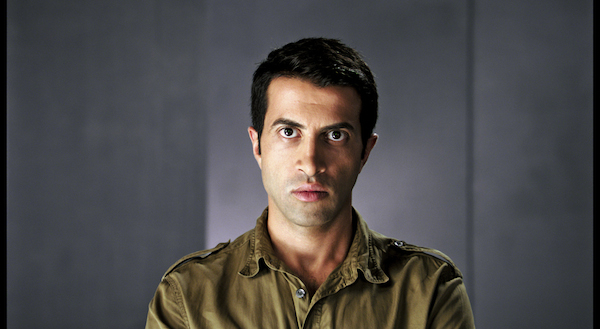

Top Image: Mosab Hassan Yousef and Sheikh Hassan Yousef, “THE GREEN PRINCE.” Photo courtesy of Music Box Films.