Photographers created a visual revolution in the 19th century by describing the world accurately, almost scientifically. They forced other artists such as painters to move in new directions, to impressionistic views of the world, to slicing it up in Cubism, to the entirely non-pictorial work of Abstract Impressionism.

Yet photographers, perhaps insecure about their status as artists, followed the painters into non-realistic work. They created expressive images with all kinds of technical tricks — blurring, distortions, reflections, double exposures, solarization, odd framing, intrusive shadows.

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art has organized a full-scale exhibition of such work, Don’t! Photography and the Art of Mistakes. It’s full of wonderful pictures — some famous, some not — though at times its didactic approach seems almost too clever.

Photographers began to explore the possibilities of non-realistic images more than a century ago. In Jacques Henri Lartigue’s Grand Prix of the Automobile Club of France of 1912, a race car zooms off the frame to the right, seeming to move so fast that its round rubber tire is elongated into an oval. In the background to the left, a few blurred spectators seem to lean to the left. It’s a great image of speed.

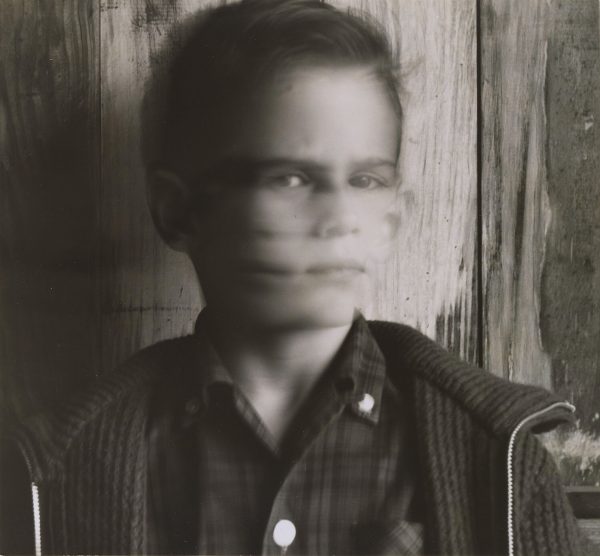

Ralph Eugene Meatyard takes a different approach to capturing movement in an untitled portrait of a young boy from about 1963. Using a long exposure, the photograph presents two views of the boy: in one he looks straight ahead at the camera, in the second he looks off to his right. The two views fit together seamlessly with a blur of motion, creating the slightly spooky image of a three-eyed subject.

Some of the photographs offer more subtle special effects. Lisette Model’s Promenade des Anglais, Nice of 1937 uses a wide-angle lens to foreshorten the view of a bourgeois man and woman relaxing on the boardwalk. The dozing man’s laced-up shoes and polka-dot socks in the foreground appear to be as large as the torso of the woman on the left.

The exhibition begins with an amusing selection of how-not-to manuals, most from the early 20th century, that explain what a good picture should be for amateur photographers. Then the show moves into a dozen sections featuring various “wrong” techniques — solarized pictures by Man Ray and Richard Avedon, for example, or the unusual use of shadows by Lee Friedlander and Lisette Model.

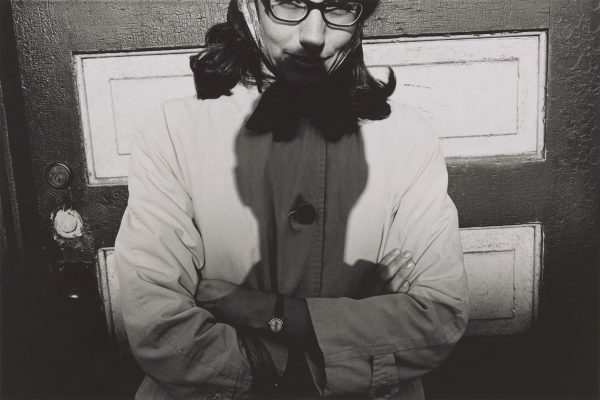

In Maria, Minneapolis, Minnesota of 1966, Friedlander inserts the shadow of his own head and shoulders over an oddly framed portrait of a woman in a raincoat. It gets your attention, though it carries little of the power of, say, Lartigue’s race car.

Don’t! Photography and the Art of Mistakes runs through December 1 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 151 Third Street, San Francisco.

Top image: Jacques Henri Lartigue, Grand Prix of the Automobile Club of France, 1912, printed 1972, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Arthur W. Barney Bequest Fund purchase; (c) Ministere de la Culture, France / AAJHL.

Skillful, Strange Self-Portraits

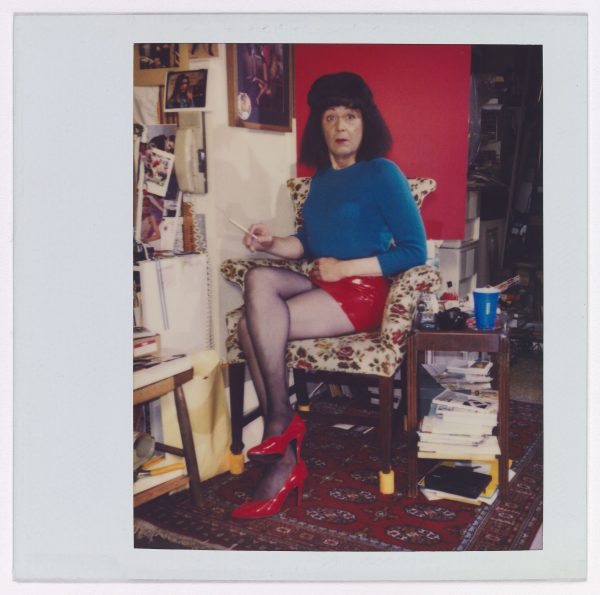

SFMOMA also has mounted a remarkable exhibition of self-portraits by April Dawn Alison, the female persona of Alan Schaefer, a commercial photographer who lived in Oakland. The small Polaroid pictures are much more than snapshots, often showing a visual wit and skill that outweighs their emotional sadness.

While cleaning out Schaefer’s apartment after his death in 2008, his family discovered a collection of more than 9,000 Polaroids taken over 30 years. Almost all of them are self-portraits in drag.

In one series of eight images, April Dawn Alison starts out as a mundane housewife loading the dishwasher, then turns to face the viewer, hands on hips, with a flirtatious expression on her face. In later shots she pulls up her skirt as if starting a striptease routine.

Almost all of the photos in the show have no captions or dates, though in one series she has annotated a couple of the prints in red marker. In the margin of one, in which April wears a blue crew-neck sweater and short black skirt and uses a wooden stool as a prop, she notes: Bust 39″ Waist 27 1/2″ Hips 37″ Wt 154. Another image in the series is dated April 23, 1989.

Most of the pictures, though, exist in a sort of historical vacuum. She appropriates visual cliches from popular culture and twists them slightly.

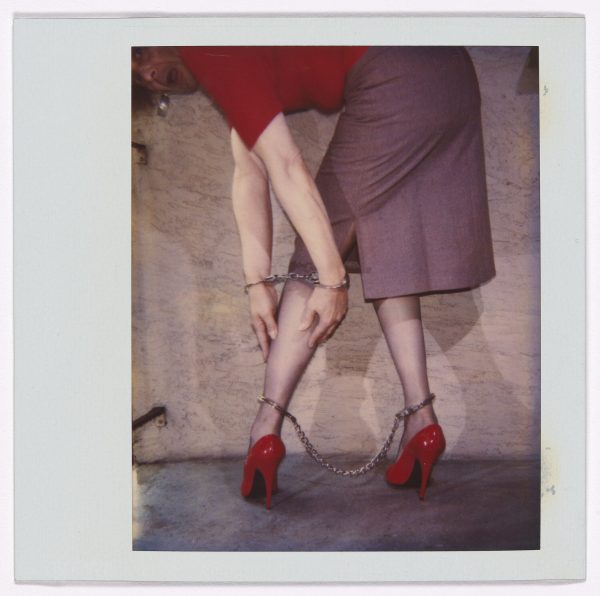

In the series with the wooden stool, she appears to be a middle-aged woman at home after a day at the office. In others she’s a burlesque figure, dressed in black corset and stockings, her back to the viewer and showing off her bare behind. Or she’s a pin-up girl in a teeny black bikini, or she evokes the S&M world by chaining her arms and legs together.

Underneath it all there seems to be, at least to me, a certain melancholy. The photographer is clearly having fun with the visual tricks, the showmanship of the images. Yet the model, in her poses and expressions, suggests something else. Sometimes she appears to be having fun as a woman; at other times she seems to be making fun of their roles.

April Dawn Alison runs through December 1 at SFMOMA. A catalog is published by Mack.