One of the most enigmatic, fascinating and tragic figures in the entire rock canon, Syd Barrett is a man shrouded in mystery. To his most devoted fans, he is quite simply a genius — a literary savant and a master of the English language along the lines of John Donne, Gerard Manley Hopkins and John Clare. To most, though, he is the the “Crazy Diamond,” a psychedelic Boo Radley who loved to write strange songs about Siamese cats, scarecrows and eiderdowns before blowing his brains out with LSD. More of a cautionary tale than an admired songsmith, Barrett and his antics have provided grist to the mill for anti-drug scare stories for decades. Tales abound of Syd’s bizarre behaviour, including hailing aeroplanes at the airport like taxis, playing one note endlessly at shows and (most famously) rubbing Brylcreem and crushed Mandrax in his hair before a gig.

Although many of these stories have turned out to be little more than exaggerations, even the most ardent Syd defender must concede that something happened to him in the late 60s. Described before as fun, sunny and charismatic, by 1968 he had become moody, tense and prone to violent rages, especially against his girlfriends.

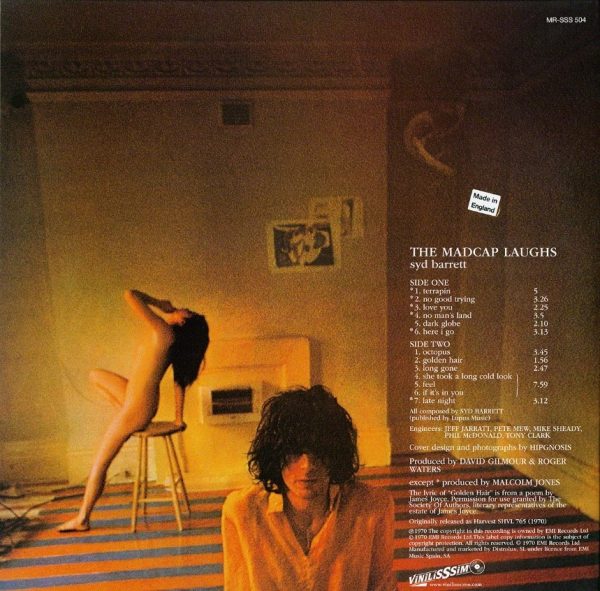

Like most things, the truth about Syd probably lies in between. The Madcap Laughs, Syd’s first and penultimate solo album, is in many ways the embodiment of this split character. A classic of the psych-folk genre, The Madcap has lasted beyond its years as a tellingly honest and open-sored self-portrait of a man in crisis. The familiar cushion between art and artist is gone. Absent of the psychedelic adornments of Piper, like keyboard layering, generous echo and phasing and avant-garde sound effects, the songs are simply Syd: his voice, words and guitar, with the occasional backing of a group. On some songs, his guitar playing is considered, melodic and entrancing; in others, choppy, painful and bordering on embarrassing. Likewise, some songs show Syd at his harmonic and melodic best; others are so basic they could be learned in a beginner’s guitar lesson. But herein lies the brilliance of The Madcap. No holds-barred, this album is an inseparable mixture of highs and lows, genius and madness, playfulness and depression. With Syd, you take the good with the bad. The choice is with the listener.

The album is everywhere haunted by Syd’s conflict with the outside world. After leaving the Floyd, he made a full-scale retreat into his own mind. Without the need to work, Syd wiled away his days sitting, day-dreaming and doping. His roommate described him as occupying a “creative vacuum” – a state of “void and avoid” in which “he’d avoid doing something because that limited him.” The thing about “not working,” Syd said, “is that you do get to think theoretically.” But while our minds offer us comfort, security and freedom, they can also cut us off from everything else – trapped within this mental prison, Syd’s songs are neurotic essays on his inability to find love, meaningful relationships or cope with himself.

Syd’s primal rejection of discipline and routine is explored on the album’s opener, “Terrapin.” Most albums begin with the single: the catchy song around which the album is built and that gets the crowds to shows. But “Terrapin” is a rather sedate affair, chugging along for five hypnotic minutes in the same slow tempo. That the album starts with such a song is simply a sign of the strange things to come. Over a well-composed and bluesy melody, Syd tells a love story through the lens of an ocean scene. He and his lover are content to spend their days aimlessly, “cause we’re the fishes… [and] the move about is all we do.” Free of obligations, Syd describes the underwater play in effortless metre and a pleasing cadence — “floating, bumping noses,” “fangs all ‘round” and “fins aluminous,” with the clever assonance and internal rhyme of “below the boulders hiding all.” Revelling in the ordinary, Syd declares that “the sunlight’s good for us!” Yes, Syd… I suppose it is.

But as the album goes on, it becomes increasingly clear that Syd cannot find such a relationship. In seeking a partner to share his own private mental space, he is attempting to square the circle. Perhaps the most harrowing song on the album, in “Dark Globe” Syd cuts a pathetic, pitiable figure. With his favoured Dylanesque waltz and just three basic chords, the Madcap cries out to his estranged lover in almost Shakespearean phrase: “Oh, where are you now, pussy willow that smiled on this leaf?” What he misses about her is not clear, especially since her promises amounted to “a stone from [her] heart.” But Syd’s grief is so great he is actually drowning. “Half the way down, treading the sand,” he is now begging. “Please, please lift a hand,” Syd pleads, his “armbands beat[ing] as [his] hands hang tall.” More harrowingly, having “tattooed [his] brain,” he knows that he himself is responsible for his despair. By the end of the song, Syd’s delivery is so pained the drowning almost seems literal. With laryngitic desperation, he makes a final plea for help, before the bubbles disappear and the song fades with a few posthumous putters on the guitar. “Yippee! You can’t see me, but I can you!” Syd sang just 2 years before on “Flaming.” Only now does he glimpse the costs of such isolation.

After the misery of “Dark Globe,” the music-hall jaunt of “Here I Go” sounds rather unconvincing. Granted, in this song Syd’s musical capacities are clearly still intact: the melody and the harmony are written to textbook perfection, with an effortless rise from A major to B minor before resolving with the E major, and the bridge making a neat Beatle-esque shift between D major and D minor. But behind the surface, Syd’s hang-ups are still evident. “A big band is far better than you,” says “the girl that [he] knew,” Syd still reeling from his dismissal from the Floyd. As the band rocked on without him, it must have been hard for him simply “to hold her hand and forget that old band.” “Love You,” one of Syd’s favorites from the record, also has a disturbing element behind the happy face. Driven by a relentless, amphetamine-level energy, Syd’s enthusiastic outpours to his “honey” soon decay into nonsense: “Ice-cream ‘scuse me, I’ve seen you looking good the other evening!” he sings. Once he’s found his lover, he cannot let go. He is literally driven to mania with excitement.

Syd’s loneliness later becomes self-denying. In “Late Night,” everywhere he looks he is reminded of his loss. Whether “when [he] woke up today” or when he lies “still at night,” in the “stars high and light” or a “spark” as “the rooftops shine dark,” Syd knows that he “wanted to stay with you.” The song begins with a neat slide riff, but his Zippo lighter approach deteriorates into meandering dissonance. Yet what else can we expect from a man that “feel[s] alone and unreal?”

Not much discussed by critics, “Feel” is one of Syd’s greatest accomplishments as a poet and a songwriter, displaying his mastery of discontinuity and impressionistic imagery. The song’s changes are like jagged brushstrokes: abrupt, strange but still flowing, with each verse containing thirteen chords. “Away far too empty, oh so alone,” all Syd wants to do is “go home” and retreat back to the comforting domesticity of Cambridge and his own mind. Meanwhile, “the blonde” whom he seeks is inaccessible. While “the crowd on her side” wail away, “she straggles the bridge by the water” and “misses her crawl”: this time, it seems, his lover is drowning. Amidst the Constable-like countryside scene of “far ley grew,” the “heady aside in a dell” and the “flail[ing] crowd,” his lover has died – “a bad bell’s ringing, the angel, the daughter.”

In “Long Gone,” Syd channels his grief like a 1930s bluesman. “She was long gone,” he sings over a catchy progression in E, “long, long gone.” After seemingly resigning himself to his bereavement, he is awoken: in the greatest moment on the whole record, the song transforms into a passionate, poetic outcry. Switching from the minor key to the major key, the organ rising and rising and with brilliant internal rhyme, Syd “wonders for those [he] loves still” within the sustained prison of his mind: “I cried in my mind where I stand behind/ The beauty of love’s in her eyes.” In the next outcry, Syd’s imagery becomes mystical and ecstatic. Comparing himself to a caged leopard “prowl[ing] in the evening sun”s glaze,” he sees his lover: “her head lifted high to the light in the sky/ The opening dawn on her face.”

“Golden Hair” marks yet another brilliant peak on The Madcap and a further outing into mysticism. Syd sets the words, originally composed by James Joyce, to an ethereal, entrancing drone in E, similar to the modal compositions of medieval churches. Against a backing of cymbal washes and a single sustained organ note, the shifting melody is beautiful and tense. “Lean out your window, golden hair,” Syd sings, his love fueled by mystery. From his room, whilst “watching the fire dance,” he hears her “singing, in the midnight air.” In a similar vein to “Long Gone,” Syd is helplessly in love with the inaccessible. Within his mental prison, fueled by hope and expectation, all he can do is fantasize and imagine.

Of course, though, Syd’s relationships never really match his semi-religious expectations. In one of the few tracks backed by a band, on “No Good Trying” Syd is joined by fellow UFO alumnus The Soft Machine, who offer a busy if strange accompaniment on drums, guitars and keyboard. The song is in some ways the acerbic successor to “See Emily Play”: while Emily, the girl who “misunderstands,” can try “another way” to “free [her] mind and play” (presumably LSD), Syd’s new girl is beyond redemption, with her advances rebuffed in witty and colorful put-downs. “It’s no good trying…,” he tells her, “cause I can see that you can’t be what you pretend.” For all her efforts, all she’s doing is “rocking [him] backwards” whilst she’s “rocking towards/The red and yellow mane of a stallion horse.” Reminiscent of Dylan a la “Positively 4th Street” and “Like A Rolling Stone,” Syd patronizingly tells her that she “should be home in bed.”

One of the rawest cuts on the whole album, “She Took A Long Cold Look” is almost the end of the 1960s put to song. By this time, the religious reverence in which Syd and the counterculture held the drug experience had faded. He had now taken to abusing Mandrax, a powerful sedative and euphoriant. His muscles relaxed and his eyes glazed, in “Cold Look” Syd can barely form the song’s two main chords. The strings buzzing against the fretboard, his playing sounds like the laboured strumming of a teenage beginner. He clearly hadn’t learnt the words, either, since you can hear him turn the lyric sheet in the middle of the song. The song ends abruptly and an uncomfortable silence takes over – “that short…,” Syd is heard to mumble. Barrett’s deterioration is all the more tragic when one considers the sheer waste of potential. Indeed, “Cold Look” contains some of the best lyrics Syd wrote. Outwardly a bitter commentary on a failed relationship, the song is unwittingly or not a partial examination of himself. In his own catatonic trances, Syd had started giving “long cold looks,” too. “Her face between she all she means to be,” she is also alienated from the outside, her caged ego like “a broken pier on a wavy sea.” In an oblique verse, Syd seems to acknowledge his own undisciplined lifestyle, with “the end of truth that lay out the time/Spent lazing here on a painting dream.” Before the band came along, painting was Syd’s passion. He wanted to be an art teacher. Yet under the tranquil haze of Mandrax and free time, Syd couldn’t even be bothered to paint anymore.

“If It’s In You” is similarly painful. After a forlorn first attempt, Syd lets it rip. “Yes I”m think-i-i-i-,” Syd screeches in his upper register, before cutting himself off. In the recorded conversation with the control room, Syd sounds defensive and agitated. “I’ll start again. I’ll start again… it’s just the fact of going through it.” In the final take, Syd’s singing waves in and out of tunelessness, and his guitar playing is basic and poorly executed. But unlike “Cold Look,” the words offer little redemption. Employing his classic childlike approach, the tale of “Puddletown Tom,” the “Colonel with gloves,” “Pamela” and “Henrietta” isn’t fun or playful – the song sounds like a demented, psychotic parody. “Did I winkin” of this, I am/Yum, yummy, yum, don’t yummy, yum, yom, yom,” Syd yabbers nonsensically. But for all its flaws, this is one of the best on the record: the chatter, the mistakes, the uncomfortable atmosphere… These were all included purposefully by his producers as an exercise in “studio vérité.” They wanted this record to be as honest as possible, warts and all.

Indeed, it’s only through Syd’s lows that we can truly appreciate his heights. “Octopus” is simply one of the best tracks he ever put to tape. For all the pitfalls of a life in one’s mind, the song is a carefree celebration of mental play for its own sake, and a papier maché poetic masterpiece in free association. It took Syd six months to write “Octopus,” and the hard work certainly shows. The melody is jubilant and catchy and the harmony sophisticated and mobile, with Syd playfully alternating keys between Bb major and B major throughout the verse. On this track, Syd gels much better with a band than on the likes of “No Good Trying” and “No Man’s Land”: backed by Gilmour’s drums and bass, the whole song just has a great driving groove. A veritable “octopus ride,” the lyrics are a cut-and-paste, kaleidoscopic English swirl of phrases, images and characters from across fiction, including children’s rhymes, Shakespeare, John Clare and William Howitt. Like an Edwardian spin on “Tomorrow Never Knows,” Syd is our shamanic guide: taking a phrase from playwright John Nashe, Syd opens knowingly, “Trip to, heave and ho, up down to and fro/ You have no words!” Taking us through fairy-tale images like the “dream dragon,” the “ghost tower” and the “little minute gong,” the octopus ride makes a detour into the woods, with “clover honey pots and mystic shining feed.” Over a sustained Bo Diddley groove in F, Syd gives an impressive and choppy blues guitar solo, before leading us back to the explosive chorus: “Please leave us here/Close our eyes to the octopus ride!”

After The Madcap, Syd released one more solo album: Barrett. Despite having some great songs, the record lacked the singular honesty and candour of his first. Fleeing London, he moved into his mother’s basement in Cambridge and for the last year of his career, Syd’s only “work” consisted of interviews.

“I don’t think I’m easy to talk about. I’ve got a very irregular head. And I’m not anything you think I am anyway.” And with these cryptic words, Syd said goodbye to the music world. He would never again say a word to the press, let alone release a note of new music, until his death thirty-five years later, aged sixty. By this time, “Syd” was long gone. The strange old man in St. Margaret’s Square didn’t answer to “Syd” anymore. He didn’t like talking about the past. Spending his days gardening, painting and cycling to the shops, Roger (as he was now called) almost seemed like a fitting subject for one of his old songs. I can imagine it now: “Old Man Roger.” It would have fit perfectly on Piper.

[alert type=alert-white ]Please consider making a tax-deductible donation now so we can keep publishing strong creative voices.[/alert]