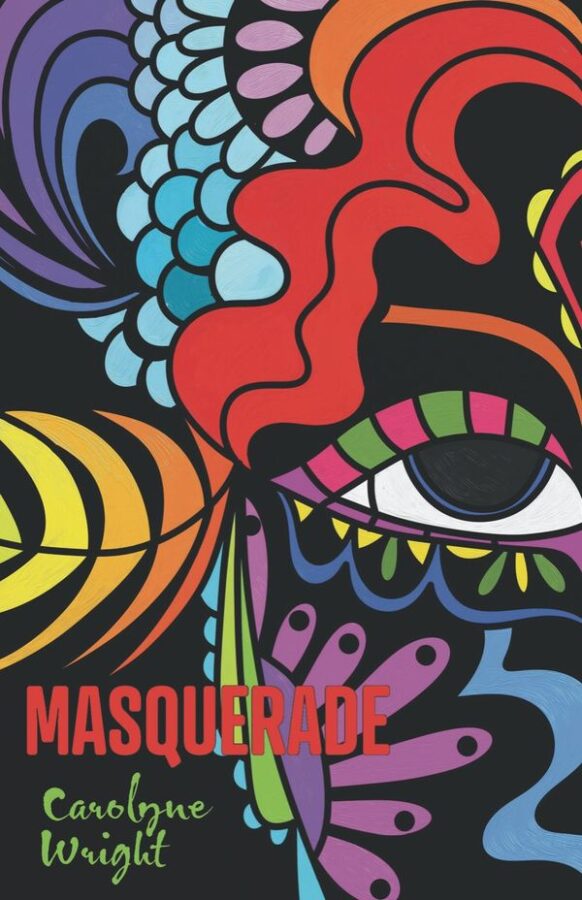

Cultural Daily’s contributor-poet Stephanie Barbé Hammer recently turned the tables, interviewing poet-memoirist Carolyne Wright. They talked about Wright’s intriguing new book Masquerade, a memoir written as poetry, not prose, about how Wright came to write it, and about crafting poems like the ones in Masquerade. Read all about it, below.

Stephanie Barbé Hammer (“SBH”): Could you say something about how this project first began? Were you already thinking about it as a big story?

Carolyne Wright (“CW”): I never meant to write a sequence of poems as memoir—I didn’t know these were in me to be written. Only a few poems emerged during the years I was with this man, as indirect reflections on aspects of our life together. The first poems to be completed during that time, and published in magazines soon thereafter, were set in New Orleans: “Faubourg-Marigny,” “Masquerade” (the title poem), and “Note from the Stop-Gap Motor Inn.” I know this because after I realized that these poems would be part of a book-length project, I began to note the approximate start and completion dates next to the title of each poem in the expanding Table of Contents.

The oldest poems from that time, though, were “The Putting-Off Dance,” “Fire Season,” “Of Omission” and “The Gondola: New Orleans World’s Fair”—poems or fragments of poems which sat for years in folders full of first drafts before I finished them. Perhaps because these poems involved self-questioning as well as tougher subjects, personal and political dislocations as well as deep-seated issues of trust, especially about other women in his life. These were questions that opened fissures between the couple, questions I didn’t know I could ask, especially in any critique of him.

There is also the story of how the “mantle” fell upon me—that bolt-of-lightning idea for the book, along with the realization, the charge, that my inner self thrust upon me, that I had to write this book. That story is a whole narrative in itself!

SBH: Since you’re both a prose and poetry writer, why did you decide to tell this story in poems and not as a prose memoir?

CW: Because both protagonists—the speaker / narrator and the man with whom she shared this complex and nuanced experience—are still living and still active, I wanted to preserve a certain dignity of privacy, to stick with the dramatic essence and not let the story bog down in guessing games about, for example, Who He Is. I have great respect for Who He Is, and as is clear, the memories here are both fond and fraught; but the story here is about two people as they were back then. Prose would necessitate going into more detail about events and circumstances that occasioned the poems, the individual people and their histories—I would have needed to tell the stories behind the poems. That deal of background would have overwhelmed the dramatic essence of the story, at least for me as the channel for the creation and shaping of these poems.

SBH: I experienced this book as a kind of family photo album belonging to a stranger, where I look at snapshots and I get to know the family through the photos, bit by bit. I think in particular of the visits to the two different families, represented here, and the scene at the bookstore. Is that right?

CW: Yes, those poems were wrenching to write, in the portraits of family members, the dynamics in those families. The contrast between the welcome shown by his mother (“I hope he marry you“) in “Majesta Blue: Mothers and Daughters”; and the rejection from my mother in the very next poem, “Through Bus Windows, Seattle” (“You need someone just like him / but white.”) could not be more dramatic.

No member of my family ever did meet this man, a fact that I found shameful given his family’s acceptance of me. The greatest pathos for me, though, was my mother, who had refused to meet my partner, but who nevertheless came to the Greyhound station and looked up at us from the boarding platform, as we were leaving Seattle. We gazed back “through the bus window’s / tinted glass,” too dark for her to see much of anything. Somehow I sensed that she wanted to accept him, and support me in this relationship, but she could not admit this to me, maybe because of my father—her loyalties were torn.

SBH: There is a huge emphasis on the city (or should I say cities) and on different interiors in Masquerade. Can you talk about the role that the city plays here and the roles of all the different inside spaces in the book? Who are your progenitors in poetry for how to write about the city?

CW: There was a lot of moving around during the years this story takes place. The towns and cities where the poems take place lend their landmarks and features to the dramas occurring between the personae who can seem like actors on location, various locations, in a film. There is a lot of walking, too, especially after dark, through the towns and along the streets of the cities.

And the interiors, recalled and re-imagined—including the interiors of Greyhound busses!—seemed to me like sets in a play. In fact, most of poems came to me like dramatic scenes—often beginning with an arresting bit of dialogue (“What’s it like, you know, with him?”; and “Quit your hollering and shut the door. . . “)—as if in a play. As I wrote I was mentally blocking out the characters’ movements as they stood or sat or gestured, or embraced in bed! All the drama classes and the acting I did in high school and college helped to sharpen this awareness, I think. I didn’t have any specific models in mind for writing about the city, but there is a line from Lawrence Durrell, from his novel Justine: “A city becomes a world when one loves one of its inhabitants.”

SBH: The importance of sound is a real through line in this collection: the lover and the other neighbors overheard next door and down the street, music played on a record player or performed live and the words of other poets and writers. What is the role of sound and how are you trying to reproduce it on the page?

CW: Jazz and the blues are woven throughout this story—not just as background music, but as an undercurrent suffusing the texture and shaping the rhythm of the poems. Musical structures—motifs, improvisational patterns, repeated and varied phrasing—inform these sequences. There is a sly little rule I gave myself, about which I kept quiet throughout the composition process—each poem has to make reference to the blues or to some shade of the color blue. I don’t know why I gave this rule to myself—it was my little secret, but it became a unifying thread that I could follow. It kept my focus on the sounds—recalling all those jazz and blues musicians we heard in clubs in New Orleans and New York, piano sonatas floating up from my brother’s basement practice room, rhythm-and-blues pouring out through the doors and windows of Bywater bars, the same Barbra Streisand song played over and over full-blast through the wall by an inconsiderate next-door neighbor in the middle of the night!

SBH: One of the things that I admire most about this collection is how you, as a white poet, attempt to bear witness to the force of racism, not just in American society, but in your own life and in your own consciousness. How did you go about tackling this issue in the individual poems and in the collection as a whole?

CW: This is potentially the most difficult issue to confront, both at the time this story took place, and later, in considering how to write about it. As a white woman aware of the fraught legacy of white appropriation, I felt constrained in what I could inscribe onto the long, bitter history of racism. What right would I have, as an indirect beneficiary of racial discrimination via white privilege, to make proclamations, even poetic ones, about race relations? But that constraint also gave me focus and freedom . . . to tell my side of the story with as much perceptiveness and empathy as I could.

SBH: When you work with a form, do you start writing immediately in that form, or do you do a draft in some other way, and then transpose into the form?

CW: In earlier books, I didn’t usually decide on the form right away—after writing a few new lines, I would sense a certain pattern that suggested a stanza form, or a rhyme, or whatever, and then I tried going with that form to see if it worked. Sometimes the first form that suggested itself worked, other times not. With the poems of Masquerade, though, as the image, the scene, the rhythm of the language, the opening phrase of arresting dialogue came to me and began to gather momentum as a poem, the appropriate form also suggested itself.

A few of the poems were assembled, particularly the (deliberately) cryptic “Shadow Palimpsests.” This poem was modeled on an excerpt from “Chronic Meanings” by Bob Perelman, published in a chapter by Paul Hoover included in Annie Finch’s and Kathrine Varnes’s An Exhaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of Their Art, a book I used for several years as a text for Craft of Poetry. Hoover’s chapter, “Counted Verse: Upper Limit Music,” put forward word-per-line count as a formal technique. The notion of counting only the number of words per line was new to me when I first read this chapter, and I found it creatively freeing.

SBH: What is next for you writing-wise?

CW: I’m writing some new poems for two future books: Mother-of-Pearl Women, a sort of poetic memoir from childhood up to the present, exploring the interweaving of personal and political history; and Solstice in the South, a sequence of poems started in Brazil, at the artists residency I held in 2018 at the Instituto Sacatar in Itaparica, Bahia. This work is inspired by the cultural life and natural history of Brazil, especially the state of Bahia, the city of Salvador and the island of Itaparica, and it will be bilingual (English-Portuguese) so that speakers of both languages can enjoy it. (I have translated many of the poems myself already, with the assistance of certain Bahians!) This is the project for which I received a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award for Bahia, Brazil . . . just three weeks before Covid-19 put the program on hiatus! So I will eventually spend four months in Bahia for this project.