Climate change is front and center in at least two of the dozens of exhibitions that make up the Art and Science Collide series now on view across Southern California museums. Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens takes a historical approach with paintings and documents. The Hammer Museum is showing contemporary artworks that try to evoke what the environmental crisis looks like now and where we may be heading.

Storm Cloud; Picturing the Origins of Our Climate Crisis, at the Huntington tells the story of how industrialization — first in Britain, later in America — led to environmental degradation. There are lots of 19th-century prints, ranging from British coal works to American railroads to a cartoon ichthyosaur — a large marine reptile — delivering a lecture to other huge reptiles about the now-extinct human race.

Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg’s dramatic aquatint Iron Works of Coalbrook Dale of 1805 updates the typical English landscape by featuring one of the behemoths that were changing the country’s economy forever. In the foreground, a man on horseback rides toward the foundry, which sits on a hill overlooking a river that cuts through forested mountains. Its enormous chimneys emit a yellowish-brown smoke that drifts over the valley. The picture reminds you of the entrance to the gates of hell.

Not all of the artworks in the show focus directly on the environment. An advertising sheet for a stylish New York clothing store, Scott’s European Fashions, for the Summer 1848, shows more than a dozen dandies modeling the latest styles, including blond fur top hats for summer and dark ones for winter. As a wall label notes, people burned coal for warmth in winter, so dark hats and coats “became the preferred style … because they showed less grime.”

The exhibition focuses on America’s changing climate as well as Britain’s. The artworks and wall texts show, for example, how the construction of the Erie Canal caused environmental damage. It explains how the plantation system in the South, with its focus on producing only one or two cash crops such as sugarcane, cotton, or tobacco, degraded the soil and reduced biological diversity. Still, the most powerful agent of climate change in America, particularly in the 20th century, was the development of an oil-based economy.

The use of petroleum rather than coal was undoubtedly a step forward, though it created its own environmental problems during both production and use. There’s a powerful 1923 photograph showing dozens of oil rigs jammed together on Signal Hill in Southern California. You can’t really see the routine oil spills associated with drilling, but they’re undoubtedly there. And then there are the drilling rigs that catch fire or burn off natural gas or excess production.

A black-and-white photograph of an oil rig, probably from the 1920s and taken by an unknown photographer, packs quite a punch. In what looks like an arid desert location, the derrick sits on the right side of the vertical picture. In the center, a man in a suit, tie, and hat strides toward the viewer. On the left is a gigantic plume of black smoke billowing into the sky. Did the man intentionally set the fire? Did one of the storage tanks in the background accidentally catch fire? We don’t know, but the simple visual image of the black smoke rising so high into the sky is astonishing.

Storm Cloud: Picturing the Origins of Our Climate Crisis runs through January 6, 2025, at the Mary Lou and George Boone Gallery of the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, 1151 Oxford Road, San Marino, California. The museum is closed on Tuesdays. An extensive catalog is published by the Huntington and Yale University Press.

Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice

In contrast to the Huntington’s scholarly and historical exhibition, the Hammer Museum at UCLA takes a contemporary approach to the environmental threats we face.

Conceived during the Covid pandemic and Black Lives Matter movement of the early 2020s, Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice tries to address a wide range of problems. As an introductory wall text puts it, “breathing is an act of resistance and survival in the face of racial inequality and a global health crisis.” The show attempts to address environmental threats ranging from rising temperatures and unpredictable flooding to deforestation and contaminated water supplies.

Unfortunately, the exhibition is a hit-or-miss affair when it comes to actually addressing such sweeping goals. Many of the works seem more interested in virtue signaling than in creating a compelling visual image or object.

For example, an array of video screens showing young people dancing on a rocky beach is technically sophisticated but mostly seems to demonstrate the dancers’ wokeness. LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photo essay on the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, is competent visual journalism but, at least for me, doesn’t really rise to the level of fine art.

Brandon Ballengee’s handsome series of small paintings of several fish and an eel draws your attention because they’re extremely well executed. But the environmental significance of the works isn’t clear until you read the wall label and learn that they are made with oil from the infamous Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Tiffany Chung, whose Vietnamese family was ordered to move to the Mekong Delta in 1975, after the fall of Saigon, lived through disastrous flooding three years later. After emigrating to the United States and becoming an artist, in 2010-11 she created a huge model of a floating village that would be flood-resistant. The artwork, stored in a jar: monsoon, drowning fish, color of water, and the floating world, is meticulously crafted, though it’s hard to grasp the meaning of the work until you read the accompanying wall text.

Still, there are artworks in the show that grab your attention immediately and require little explanation. For example, there’s a pair of large 2024 paintings by Yoshitomo Nara called A Sinking Island Floating in a Sea Called Space (shown in the background of the above photograph). Each depicts a little girl who is almost up to her nose in water. One is angry, the other is anxious. “Why did you put me into this situation?” they seem to be asking.

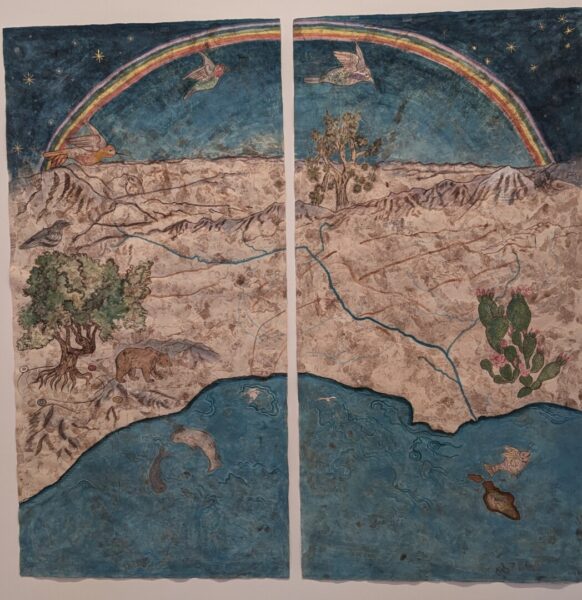

Another pair of paintings, Sandy Rodriguez’s “You Are Here,” is a faux-primitive map of the Los Angeles Basin before the Americans arrived. There are fish swimming in Santa Monica Bay, and a bear catching them for food; there’s a huge cactus, a gnarly tree, birds overhead. The whole thing is topped by a thin rainbow extending the width of the two paintings. It’s a fanciful, almost cartoonish scene, but you want to believe it.

Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice runs through January 5, 2025, at the Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Boulevard, at Westwood Boulevard, in Los Angeles. The museum is closed Mondays. An extensive catalog is published by DelMonico Books.