One-person shows conceived, written and performed by their authors, are a form of performance art. There are not many artists who specialize in working on such a personal canvas. For some, the focus on the form comes as an adjunct to acting (think Hal Holbrook and Mark Twain Tonight). In the case of the multi-talented mime, actor and clown Bill Irwin, the one-person show is an extension of his multiple skills (acting, miming and clowning). And for still others, such as Anna Deveare Smith, the point is the surgical dissection and reconstruction of events for all to see.

Dael Orlandersmith, however, is a performer who processes solo performance through a subjective and strongly poetic approach. As both writer and performer of Until the Flood, now at the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City, the work is a reaction to other people’s views, molded by her own internal perceptions and given voice through her artistic sensibility.

Until the Flood was a 2016 commission of the Repertory Theatre of St Louis. Director Neel Keller’s light touch has been guiding it securely and almost imperceptibly from the start. Its focus is the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown, a young black man, by Darren Wilson, a young white cop, in Ferguson, Missouri.

Sadly, the killing of a black person by police is not much of a surprise. What is a surprise is Orlandersmith’s ability to weave reactions to that incident into a literary whole. As opposed to just offering reportage, she filters other people’s responses through her own internal lens. The characters she impersonates on stage are composites, drawn from people she interviewed. Her 70-minute performance provides an even-handed account of a variety of responses from a narrator and a diverse group of eight “witnesses” — young, old, man, woman, black, white, liberal and not.

This artist’s primary strength lies in a strong poetic spine. It’s a poetry of tough love. It owes everything to clear vision and innate honesty. Her second strength, with the merest of costume and vocal changes, is a capacity for a deep and wide understanding of the characters she so fully inhabits.

These “portraits” travel securely from Louisa, a retired black school teacher, to Hassan, a black 17-year-old reeling between seeking a “right path” for himself, to wishing his married-with-children history teacher were his dad (“Take me home wit you…,” pleads his inner voice. “I want you to be my father…”), to just yearning for some sort of normalcy. “I’m thinking,” he tells us, “of the kids that have parents, both parents. Married and carin’ about them… I’m 17 man. Sometimes I feel seven, sometimes I feel 70… I want out!”

Another high-schooler named Paul harbors similar feelings. He lives in the same public housing Michael Brown lived in and hates it (“looks just like a prison”). One year of school to go, he tells himself. “Every day I pass that shrine to Michael Brown I think that could be me… Please God, let me get out. Just let me get out…”

But Orlandersmith does not hesitate to also take on Rusty, a retired white cop who’s seen it all and has conflicting emotions about the Michael Brown incident because he knows how complex are those confrontations. And then there’s Edna, a black universalist minister with a strong sense of fairness and very open mind, who encounters Michael Brown’s parents. Michael’s father still struggles to forgive Wilson, but Michael’s very young stepmother forgives him with an open heart, prompting Edna to comment, “That young girl, Mrs. Brown, has more God in her than I ever could…”

The keys to Orlandersmith’s piece, however, lie with its two most forceful souls: Reuben, a black barber, and Dougray, the scion of what is commonly referred to as white trash.

Two privileged college girls — one white, one black — invade Reuben’s barber shop on a mission to rescue someone. Anyone. To Reuben, who owns his shop and enjoys his life, their arrival is an invasion of his self-respect. “I am not a victim,” he explains quietly before dishing out a tough lesson in social boundaries and sending the girls packing. “By using the Michael Brown case in this way… you have taken on the very bigotry you claim to despise… The both of you know nothing, nothing at all.”

Whether the girls walk out any the wiser is less important than the lesson proffered. Reuben’s not the first or last black person to be offended by tone-deaf white presumptions. Connie, a white teacher whose very good friend is Margaret, a fellow teacher who happens to be black and with whom Connie shares wine, friendship and confidences — makes the mistake of expressing sorrow over Michael Brown and Darren Wilson. “My God,” Margaret explodes. “How I hate Liberals! At least with a bigot I know where the hell I stand.”

Orlandersmith’s most incisive portrait, however, may well be that of Dougray, a man born into a family he despises and that despises him back for being different. His drunken father denigrates Dougray for liking books. When in an alcoholic fit Dad burns one of those books, it’s one provocation too many. Dougray leaves for good, making his way to some financial success as a landowner and family man, and displaying a seeming level of understanding — until he doesn’t.

“There is a theme throughout [what] I write…,” Orlandersmith has said of her work, “about childhood and the sins of the father, the sins of the mother, and how people take on the very thing they don’t like about their parents and they become them.”

It is this balance and depth of intuition that makes Until the Flood compelling. Orlandersmith’s work displays a deep acceptance of flawed human frailty and the helpless contradictions in all people. Until the Flood escalates in power and vision, ending on a poetic riff that is at once an unanswer, a lament for the state of affairs — and a way of saying, “you decide…”

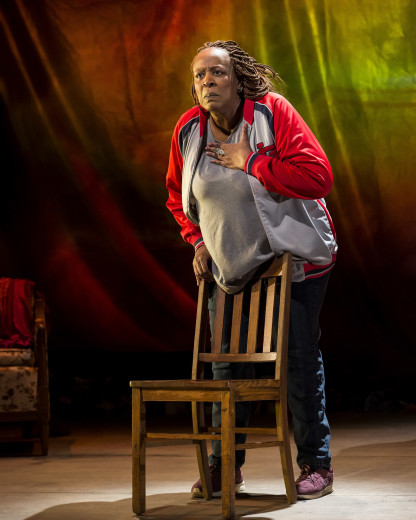

Top image: Dael Orlandersmith performing in her play, Until the Flood, at the Center Theatre Group’s Kirk Douglas Theatre.

Photos by Craig Schwartz

WHAT: Until the Flood

WHERE: Kirk Douglas Theatre, 9820 Washington Blvd., Culver City, CA 90232.

WHEN: Tuesdays-Fridays, 8pm; Saturdays, 2 & 8pm; Sundays, 1 & 6:30pm. Ends Feb. 23.

HOW: Tickets: $30–$75 (subject to change), available at (213) 972-2772 or online at CenterTheatreGroup.org, or in person at the Center Theatre Group Box Office at the Ahmanson Theatre. Groups: (213) 972-7231. Deaf community: Info & charge, visit CenterTheatreGroup.org/ACCESS.