As two major cosmopolitan centers, New York and Los Angeles have always been in a kind of tug of war for notoriety in the arts. Certainly in the arena of visual arts New York has historically been the center of the market – a place where serious global impact is delivered and exchanged – whereas Los Angeles has been acknowledged as the territory of new creative frontiers, new content, and new vision. If the old adage still stands that if you can make it in New York you can make it anywhere, then as the NY to LA transplant and musician Moby said, Los Angeles is the place where you are “free to fail”.

A week or so in advance of leaving for New York myself to shoot a dance film at globally recognized architect Bjarke Ingels (of Bjarke Ingels Group – BIG ) major new flagship building Via 57 West – with its monumental 16 ton, 8 story sculpture entitled Flows Two Ways created by NY born, LA based visual artist Stephen Glassman, I sat down for a convo with the latter and Aaron Paley, innovator, cultural leader, and founding executive director of CicLAvia, and President and Co-founder of Community Arts Resources (CARS). With Paley’s singular cultural vision for Los Angeles and Glassman’s for art in public internationally, I had suggested the two discuss Stephen’s new work and their thoughts about the intersections of art, architecture, community, and cities. I was interested in how both approach cultural impact at a civic scale, and the different and similar ways that what each does speaks to the possibilities of what a city can become.

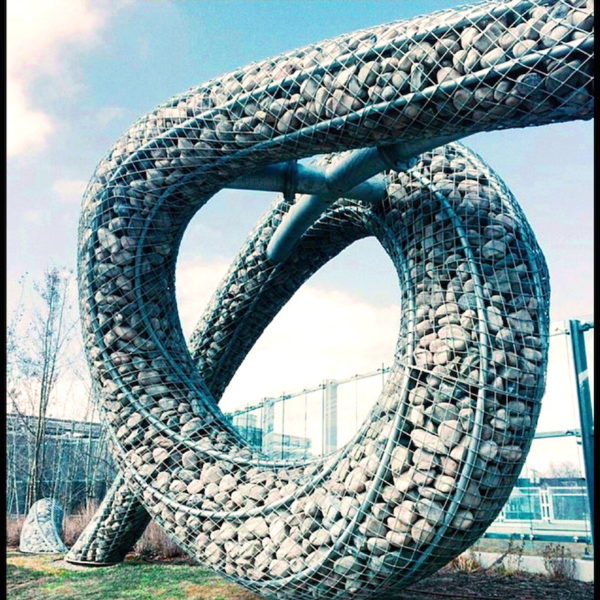

VIA 57 West, developed by The Durst Organization, is a mixed use, 750-unit, residential, tetrahedron that stands 35 stories tall. Located on West 57th Street in Manhattan, VIA was just awarded the prestigious DAM International Highrise Award. The building is a wonder of structure, scale, space, and civic transformation (scroll down to see time lapse of 30 day installation of Flows Two Ways at the end of this article).

Full disclosure: Stephen is my husband, and we both met Aaron Paley decades ago when he was working with the legendary Scott Kellman at Pipeline in DTLA, which was a very different place then. I asked Aaron what made him interested in Flows Two Ways.

AP: My own work with Community Arts Resources and CicLAvia parallels both your trajectories. I’ve been engaged with how to create temporary public space through festivals, events, art projects and other strategies. Over the years, my experiences with public space have grown from small-scale events on sidewalks and in parking lots to projects that are on the scale of Los Angeles, with miles of streets and hundreds of thousands of participants.

And, I’m obsessed with how art interacts with people within the built urban environment. There’s this complicated web that is built with these four elements: art, people, cities and built structures. On top of that, there’s the issue of time – temporal nature – temporality – and as someone who produces live events it’s a part of my sense of any piece. So when Stephen told me about this project, and my good friend and former business partner Aaron Slavin became engaged in producing it with him, how could I not be interested?

So Stephen, give a brief elevator pitch for what Flows Two Ways is. What is it?

SG: Well, Flows Two Ways is an 8-story sculpture integrated into the façade of a NYC skyscraper that serves as the entrance to, and the East facing view for VIA 57 West.

AP: Right. Bjarke Ingels is now considered a major super star. So, how did you get the commission?

[alert type=alert-white ]Please consider making a tax-deductible donation now so we can keep publishing strong creative voices.[/alert]

SG: Really, to make a long story short, I was an art student at SUNY Purchase, and working as a Chief Preparator for The Neuberger Museum, where I worked with a lot of the artists from the 80’s like Irwin, Pfaff, Borofsky, Christo, Nevelson, Di Suvero. At that time there was this quiet, humble, gentleman sculptor working in the woods of Westchester who needed an assistant, and he reached out to me. It was David Durst, who is one of the three brothers that ran The Durst Organization. But you would never know… He was a very understated guy, modest house, hard working. That’s the kind of family they were. We just took a liking to each other and later he hired me to paint his house with his eldest son Jody, who is now president of The Durst Organization.

SE: Whenever Stephen was in NY for whatever reason, David would invite him to lunch. On Wednesdays they would have family sushi lunch, and he would bring a book, or something he was working on. He would just visit them, show the book or whatever, and not ask for anything, just two artists sharing work. This, this went on for years.

AP: So you kept up a creative, artistic, intellectual conversation about what you guys were each up to?

SG: Yes.

AP: So then, they hire BIG, somebody who hadn’t built anything in the US to take on this huge commission, and that’s already a major–

SG: It wasn’t at the time. Bjarke was pretty much unknown here.

AP: And then at what point do they say, “Oh we need something here?”

SG: Well it was about a month after they committed to Bjarke that I was in NY and actually, David Durst at that point was retired and falling into the throes of Alzheimer’s. But we went out to lunch, Jody, David and I. David didn’t remember me at that point, but I had brought a book of recent work and showed it to them, and David was completely absorbed, articulate, and conversant… And it was kind of an inspiring moment. It was at actually at that moment that Jody said, “You know we just embarked on this new project with this great, cool, young architect out of Denmark, and I think this might be the perfect opportunity for us to work together.”

AP: So at that point did they know where Flows Two Ways would be installed?

SG: No. No one had any idea of what anybody was going to do. This was 2009.

AP: So then was it a process with Bjarke in terms of figuring out what it would actually be and where it would go? What was the process?

SG: No, it was very limited in terms of working together, there was only some thinking together. After that first meeting, Jody brought Bjarke and Beat Schenk (Director/Partner BIG NY) into his office and introduced us, and we had a very, very brief conversation. He had already checked out my work and remarked on several pieces that caught his eye.

AP: Okay. So like “We’ve picked Stephen, he’s an old friend, he’s great, fantastic guy… He’s going to do something in the development.” And Bjarke was “Great! I love dat!”

SG: Well, Bjarke is all about “Yes is more.” He’s very, very positive. So there were a couple of quick conversations. Meetings with Bjarke were always short and impactful, lots of laughter. We met a few months later at Harvard where he was teaching. Bjarke remarked that he’s very intrigued by the history of sculpture and skyscraper that originated in NYC, and continuing that legacy. Specifically he said that they mysteriously coexist as two entities that are completely independent yet connected.

AP: What… sculpture and skyscraper?

SG: Yes.

AP: So what were you thinking when you first started on this and how did the idea actually start taking shape in your head? What’s the process? Because it’s a long way… we’re just having this idea of sculptures and skyscrapers right now.

SG: Right.

AP: And it’s interesting, because – isn’t there like a one percent for public art program?

SG: No.

AP: So there’s no necessity for The Durst Organization to do this? So this is a real feather in their cap in terms of being…

SG: Philanthropic?

AP: Yeah. They’re being patrons of the arts. And no one’s got a gun to their head saying, “Put art here.” They’re just doing it.

SG: Yes. One of the amazing things about this project is that it wasn’t like they said we have a million dollars or two million, or whatever…They just said lets do something. And it could have been a drawing behind the concierge desk or it could have been this. We had no idea. And it went from yes to yes to yes to yes to yes. And it grew, just out of agreement.

AP: So they say, “Let’s do it on what probably is going to be one of the most important new types of architecture to hit Manhattan in thirty years, forty years.” Okay, that’s good! So how does your thinking evolve? What’s the process now?

SG: Well, the project developed from this skyscraper to an entire block. Suddenly the skyscraper was going to be half the block and they were doing three buildings, one of which was already existing. So it became more about a neighborhood and less about a single building.

AP: Right. And did the form of the building, which is unique and kind of revolutionary in many ways, have any impact on what you did?

SG: Yes absolutely. The building was a radical and aesthetic breakthrough that I had to be in dialogue with.

AP: And are you thinking about the work you’ve done up to this point, like with bamboo? Is that what you’re thinking in terms of materials at this point of your imagining?

SG: Well, you really try to think nothing.

AP: Oh really?

SG: Yeah.

AP: So…You’re really just looking at it like, “I’m going to get inspired.”

SG: Yes. That it could be anything.

AP: Wow…

SE: I think you want to start from nothing. When you’re creating work and you go in with bunch of preconceived notions or suppositions about what it is you’re going to do, then you’re already limiting yourself. Whereas if you go in with a blank slate and you just kind of leave yourself open to what might be and what might occur then there are more rewards to your process.

SG: And I think also, and I would talk about this with some of my assistants, that you keep doing your work. Whether you’re doing it with a skyscraper or you’re doing it with sticks and stones on the side of a riverbank, you keep doing your work. And at a certain point you have to trust that what you’re doing is relevant. And when your work intersects with opportunities that present themselves, then you learn to trust your instincts and respond intuitively.

AP: So at what point was the thing that spoke to you that said, “Oh! This is what I want to do”?

SG: They brought me there for one week to meet with all the stakeholders, to further research and analyze the opportunities of the entire block. At the end of that week they wanted me to meet with ownership and sketch out some ideas.

SE: And they really wanted him to just sketch on a napkin.

AP: Right, right.

SG: They said “No pressure” (laughs). Well, in the course of that week I had a session with Beat Schenk. And in this meeting we had a big ‘Ah ha’ moment. It occurred to us that the whole building was kind of like this pyramidal Roden Crater, facing the Hudson, facing the light, facing the water. The building faces west, and the predominant views are west, and these views are about the sky and the river. But looking east we realized that there was this unfelt cacophony of vertical edifice, that the whole east view was just more buildings.

AP: Right.

SG: And, because one of those buildings, the Helena, was designed to have another building right up against it, this gigantic, concrete, shear wall was exposed and emerged as a significant swath of the east facing view. And we all realized we could shape the experience of looking east. Suddenly the experience of being inside the building looking out became malleable, because Durst owns the whole block, and we all realized that this artwork could in fact become the East facing view.

AP: Got it. So it’s interesting because it’s about the experience of the block. I don’t think I understood till just now that Flows Two Ways is not on Bjarke’s building, but that its part of the experience of Bjarke’s building.

(photo by Matt Butterfield)

SG: Right.

AP: Okay so now I’m curious… At that point in the process what’s in your head about what it is?

SG: Don’t know.

AP: Something on that wall, something on that façade…

SG: Yes.

AP: And they asked you to come up with a schematic design or something like that?

SG: We constructed a “road map” and the first phase would be concept development, beginning with materials, concepts, forms, and then image. Then after image it would go into design development.

AP: What’s interesting for me is that sometime before this, you were creating site-specific installations, time based work, and performance art. All of the sudden the bamboo thing took off, and bamboo started becoming your principal medium. All this then lead to the Urban Air idea (www.urbanair.is).

So sketch out from your sense, what prepared you to do this?

SG: Well, I think that my search has really been about scale, gesture, and social impact.

AP: Hmm. That’s beautiful.

SG: You know, in two dimensions you have figure/ground, but in three dimensions, and even more in the public realm – in sculpture and more specifically public sculpture – you have content/context. So those two things reverberate. You know, when I did Urban Air I said if the world is a bell then art is the hammer, and the idea was to bang up against context to generate new content.

AP: So in your career before this, what other public art commissions did you get? What did you do? What do they look like? How were they received?

SG: Going way back, after the LA Riots, the Northridge Quakes, and the Malibu Fires, Cultural Affairs gave a lot of small grants to artists to move into the affected areas, and I started doing bamboo installations. There was a piece I did with an airplane, “Amelia Flies Again.” It was done in the Pico Union area in this old school yard. We created a giant freeform structural bamboo gesture behind a schoolyard chain link fence. We got this discarded movie mold of a World War II airplane, and put it up on the bamboo structure so that it appeared to be flying. That caused an unexpected reaction… it generated an unintended social impact and upset the Salvadorian residents.

AP: Oh, it started having different implications for them?

SG: Yes because during Reagan’s war, the US supported the aerial strafing of peasant villages to drive them out of the forest, denying the guerillas safe haven. Many of those refugees ended up in this neighborhood.

AP: What happened?

SG: So there was an intro to a Garcia Marquez book I was reading at the time that said, “When color is added to history it becomes myth,” or something like that—

AP: So, did you paint the whole thing?

SG: I brought in these graffiti artists I was working with and we painted it – we painted the walls and we painted the plane. We did this cosmic, fantastic, psychedelic stuff, which put it into the realm of myth, just like Marquez said. It became more dreamlike and a more positive” trigger.” That body of work, which this piece was part of got me invited to Bali, for the Fourth International Bamboo Congress. I did a structural and gestural bamboo bridge there that five thousand people had to cross in a weekend. And when the work got structural, that’s when it caught the attention of the architectural world. And then I started getting big art commissions.

AP: Like what?

SG: Like, “Southeast Shear”, in Arkansas, which was an nine-month Clinton White House Millennium commission. After that was LNR Warner Center in Woodland Hills, Calgary, Salt Lake City, Seattle…

AP: So at this point the work is…?

SG: Permanent.

SE: I think that for a long time people had this idea that Stephen was only working in bamboo. To this day people ask if his large-scale permanent commissions are in bamboo.

SG: Even Jody thought we were going to do something with bamboo.

AP: Well, I mean I have the same thing with bicycles and CicLAvia. Everyone talks to me as if I view the entire world through the lens of a bicycle. And that’s how I frame everything. No, I didn’t create a bicycle event, I’m pursuing public space, and CicLAvia emerged as a public space event. But now, because it’s so big and it’s so identified with bicycles, everyone thinks I’m a bicycle person. So bamboo was the medium you used to express yourself at that point?

SG: Well, bamboo was like my ‘acoustic’ medium. It was drawing in space.

AP: Really what you’re doing as an artist is you’re looking at context and content, that’s what you’re playing with no matter the material. And as you said, it’s the place that inspires you. So you went to this place with fresh eyes. But you got there.

SG: But it comes from a certain spirit. I’m glad you brought up CicLAvia. You know there’s that Herzog film, Fitzcaraldo. At the end of that movie, the boat is released down the rapids as a “medicine.” That is breathtaking spectacle. For me that’s like CicLAvia, or doing dance through a public building, or a high wire crossing – it’s like this purifying event. That’s what I mean by a sculptural gesture on a civic scale.

AP: So do you still see impermanence as a really important part of the vocabulary that you’re playing with?

SG: Yes, because it opens up so many ideas. It was theater and performance that gave me the skills of concept, collaboration, scale, and production.

AP: And how does Sarah’s work inspire you?

SG: Sarah’s work is very emotional and compassionate. And the value of that is a compass for me. And as a medium, I think dance is really something from nothing. There are no drawing instruments, there’s no paper….

AP: It’s like you said… It’s human gesture.

SG: Yeah, and it’s really purely that. And the way it can pull form, it’s like music or singing. I’m always in awe of that stuff. How this form is like smoke… It can just be there, so present and powerful, and then poof, it’s totally gone.

SE: And this is part of a dialogue that we have all the time… About public art, about whether it’s ephemeral or dense. And that brings us to the intuitive gesture on a civic scale.

SG: And it has a lot to do with context and content. When you think about the most ancient amphitheaters carving out this space for performance, or for music, or creating opera houses. It’s kind of amazing, you know when I first went to the opera houses in Florence, they’re so small, and they’re these hugely ornate, magnificent works of art strictly for a song.

SE: Yes, something that disappears! And as somebody who does site-specific work, I really believe in the ghost imprint that a performance can make. I think that when you create a memorable experience of spectacle or performance, something ephemeral that is there and then it isn’t, and you transform a space, you leave a ghost imprint in the collective conscience of all the people that were there. And that’s really powerful because then you’re tapping into something that’s uniquely human which is memory.

AP: I feel the same things. I love that metaphor. So going back… I’m teasing out your progression here… you start doing temporary public site-works, and that evolves into large-scale permanent commissions. So at this point, by 2010, you have a broader palette. Your repertoire has broadened, the arrows in your quiver have multiplied, and the tools are greater that you can pull upon that inform what you know when you come down to thinking and acting instinctively. And that’s because you’ve done your work. So what materials were you playing with in the permanent installations?

SG: Concrete, metal, landscape, stone…

AP: And do you feel like some of those were pre-cursors to this work in any way?

SG: Not really, though certainly Flows Two Ways represents the sum total of my knowledge and experience to this point.

AP: That’s interesting… And why?

SG: Why? I’ll tell you, it’s always about something from nothing. That’s creativity. It’s about that moment, right? And it has to be something that’s never really been done before. The work has to embrace the true unknown and create something that has never existed before. I couldn’t have just done a bigger bamboo variation.

That said, with the time frames and production context, every idea had to be seamlessly attached to build-ability. And I have enough experience that I can think that way and move with velocity. There was a moment in the final design meeting, when we were in the conference room with the Dursts, Hunter Roberts, Milgo Bufkin – one hundred-year-old NYC building companies, literally the people that built modern Manhattan – The World Trade Center, Statue of Liberty…And they looked at my studio drawings, and said, “Well, we’ve never really built anything like this before but it seems like it’ll work.”

AP: It’s a very beautiful piece. It’s as you said… an aluminum jigsaw puzzle. What do you see when you look at this piece?

SG: It’s really a meditation on the Hudson River.

AP: Of course! As soon as you say that it’s about the river, that’s what I see. I only had a sense of the abstract before.

At this point, Stephen shows Aaron some preliminary concept drawings and a small bamboo and stone sculpture that he had done early in the process.

AP: So you built this? And why did you think of this, because you were looking at the Hudson?

SG: No, not at all. The Hudson came later.

AP: (Laughs) The Hudson came later? This is so clearly in the piece. So you know you’re working on this piece, and you create this piece of sculpture as a kind of sketch?

SG: Not really, I was just working. It was more or less my personal search at the time the commission began.

AP: And so at what point did you go “Oh yeah, it’s the Hudson”?

SG: Well there were a lot of different images, concepts and forms I explored using this medium, and the concept they chose was the one that had a direct reference to the river.

AP: Now I finally get it… I finally understand the title. The Hudson flows two ways, which not everybody knows, because of the seawater that comes in and the fresh water that comes down. I was thinking you’re referring to the street itself in terms of looking east and west. What else does Flows Two Ways mean to you?

SG: Many things, sculpture and skyscraper, building and gesture, river and city …

AP: Are we back to figure and ground?

SG: Yes.

AP: So now the building has the Hudson on two sides. The Hudson defines the building.

SE: Let me point something out here. A designated percentage of the building includes affordable units, and a large portion of these units face east…. facing what was previously the concrete shear wall. So I think there was an unspoken understanding or a realization that there was an opportunity to not marginalize the view of this whole side of the building.

AP: Right. So even the people who have subsidized apartments still get a view of the Hudson.

SG: Right.

SE: But theirs is a metaphor.

AP: They get to look at the art!

SG: A lot of people are requesting the view of the sculpture.

AP: Really?

SG: Yes.

AP: So maybe you also increased the value of the property because you took an east facing view that would have been renting for a dollar a square foot and now it rents for two dollars a square foot, so it’s actually been enhanced…Like the measurable impact of art which gets you into –

SE: Value added amenity.

AP: Which is why it’s worth it for the developers. So when they make an investment they know it’s going to pay off. Its wonderful that they did it anyway but there are measurable impacts that art can bring to real estate. And they recognize that. They’re smart real estate people.

(photo by Chun Y Lai)

SG: Another key aspect of the building relating to this view and the block is this notion of open space. They could have put twice the units in that block, and they didn’t. The Dursts are the leading builders of green skyscrapers in the world, they’re active, active environmentalists. There’s this whole 20,000 square foot courtyard, and then the private street. We did a site analysis of where the sky touches the ground throughout the block, and its very unique for NYC. So there’s this notion of value added as open space. And then a thought occurred to me: Can a façade be open space?

AP: Right, right. That’s what you were talking about. So you basically took the open space, which is on the horizon, and made it on the vertical.

SG: Right.

AP: So you created this open space for these people on the vertical that didn’t exist before. Open space is usually on the horizontal plane, meaning I can go out there onto that public plaza and walk around. But what you are saying is that you see the open space on the vertical plane, which actually creates a sense of open space for the people who are looking at it. So the façade is no longer a façade, its actually open space.

So I really wanted to have this conversation that the thirty years you were in LA, you were given this whole palette to play with that LA is unique in being able to provide. There are few places in the world like LA that give artists this opportunity to create great work on a world scale, but not have the whole world looking at it. We were working on world-class stuff that nobody was paying attention to.

SG: Right, right.

AP: I think it’s really important to mention the role that LA plays in nurturing creativity and nurturing you. Because you wouldn’t have been able to do this if you hadn’t gone through this whole trajectory.

SG: Well, LA is a horizontal city and New York is vertical. In LA you have this ever-present sky…It’s present in every photograph of LA.

AP: Well how did that shape you? I think the metaphor you were using is that the hierarchy is horizontal as well.

SG: Well, in my mind the 21st century world got horizontal. It was like an unseen new order. The Internet generated a horizontal model, like rhizomes of bamboo. And you know this horizontal reordering of the world became my context and content. And this is one of the concepts I specifically explored with the Dursts. VIA, a skyscraper, began as a singular vertical statement, but in the end it became a symbol of open space, neighborhood, horizon. You know the light goes through it, the land goes through it, the river is omnipresent…And even though it’s very tall, it’s 460 feet or something, that’s not the way you think of it. Certainly, it’s an iconic part of a skyline, but it’s very much about open space, and I responded to that.

At its essence, Flows Two Ways speaks to a new relationship to the horizon. I can’t help but believe that part of that comes from living and working in a horizontal metropolis.

So, my last question is where do you go from here…What’s next for you?

SG: Urban Air is next.