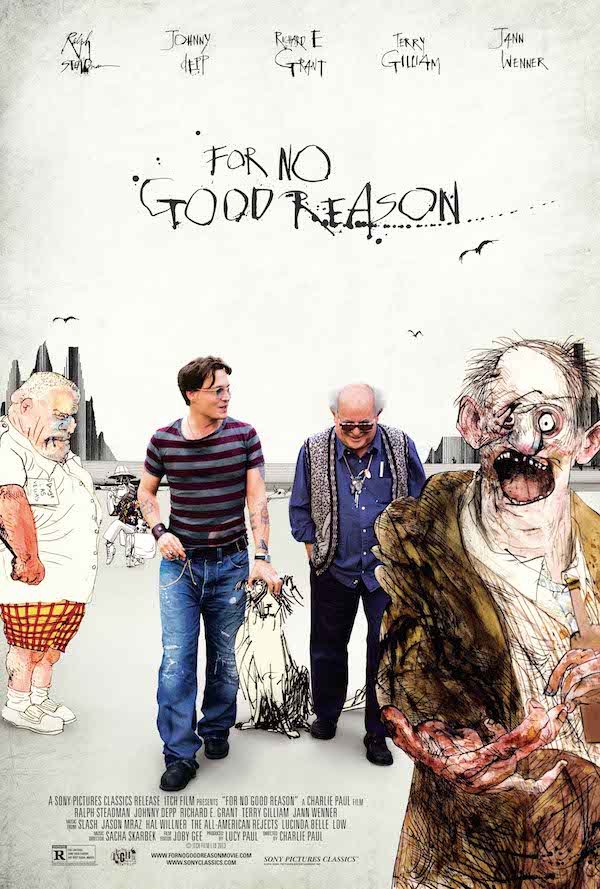

Accomplished British commercial director Charlie Paul pays tribute to his artistic hero, the legendary Ralph Steadman in his documentary feature, For No Good Reason. Paul developed the filmic portrait over fifteen years and seduces viewers with a visual and aural inventiveness that provides a perfect match for his subject.

Even if Ralph Steadman’s name does not trigger immediate recognition, Steadman’s iconic artwork should be familiar to most from the published novellas, articles, and essays by the notorious Hunter S. Thompson. Steadman initially collaborated with Thompson on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and the two continued to work in partnership over many years, covering adventures they shared at the Kentucky Derby and Honolulu Marathon, among others. For No Good Reason explores the tempestuous relationship of the prodigious, temperamentally-strained odd couple. “To him I was weird, and to me he was weird,” Steadman confesses. Yet Steadman recognizes that in meeting Thompson, he had scored a bull’s-eye. “I met the one man that I needed to meet and work with,” he concedes.

Charlie Paul’s documentary film, For No Good Reason, offers a rich and thorough exploration of the creative output and process of the great Ralph Steadman, and by extension of the artistic process itself. Along for the ride, Steadman is joined by his good friend Johnny Depp. For No Good Reason features interviews with Terry Gilliam and Richard E. Grant, and music from Slash, All American Rejects, Jason Mraz, James Blake, Ed Harcourt, and Crystal Castles. The playful marriage of form and content in For No Good Reason is delightful fun and daring; the film is stimulating and entertaining at every turn.

During their recent stay at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco, I had an opportunity to speak with documentary film director Charlie Paul and his producer and wife, Lucy Paul, regarding their thirteen-year odyssey in the making of For No Good Reason — for every good reason.

Sophia Stein: At the beginning of your film, the camera zooms over the books and objects in Ralph Steadman’s studio like an airplane flying above a landscape, with this soundscape of splashes and the scratches. I was immediately drawn in. I found myself questioning for a moment if I had come to watch a documentary film or a fiction film? The opening is so cinematic. What was your inspiration for that magical opening?

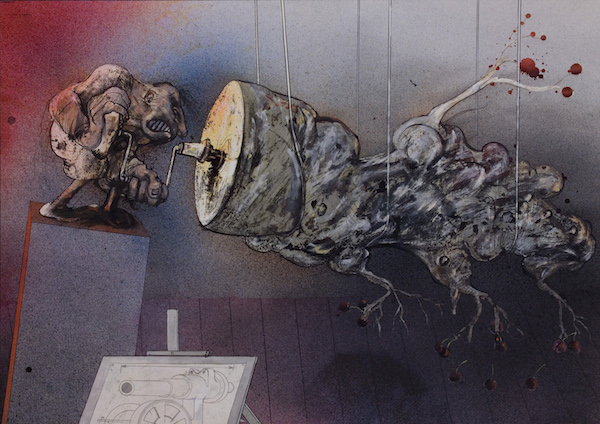

Charlie Paul: From the very beginning, I believed the film should be an artistic adventure. I knew that if I was to represent Ralph’s art, the film would have to share a unique artist’s vision. So the film is full of beautiful, highly-produced moments, like that sequence of motion control flight, followed by some very scrappy stuff — seeing the edits, the clapper boards, and all the mess in filmmaking, that is also Ralph’s art. Ralph will use any medium he needs to convey the story. Ralph can do the most exquisitely fine paintings and drawings, highly representative of what he is looking at. At the same time, he can draw the most visceral and ugly and scratchy images. So the film is a mixture of extremely beautifully polished work, as well as, rough and abrasive work. That to me was how I was going to represent the breadth of Ralph’s artistic abilities.

Lucy Paul: As a filmmaker, in many ways, Charlie, you have always been fiercely independent. You have always had a good knowledge and an understanding of your kit. You have always had your own filmmaking studio and been very self-sufficient. A lot of the film was physically put together by you, yourself, in your studio, playing with Ralph’s art when it came in and with how best to film it. In terms of production, there was a lot that went on in Ralph’s studio, and then there was also what went on in our studio. We are very fortunate that we’ve got this amazing motion-control rig.

Sophia: What does a motion-control rig enable you to do?

Charlie: A motion control rig is a large computerized tripod which allows your camera to move in a pre-programmed way. You can move the camera over a subject with precise moves, focusing, and timing. It allows you to have full control over your medium. It’s often used in advertising and very high end filmmaking. It’s an expensive and difficult piece of kit to use, but it means that your intention in your shot can be fully realized.

Whereas quite often in documentary filmmaking, you film something and that will be the best you get, I had the privilege of being allowed to take Ralph’s art from his studio back to my studio and control the environment in which I filmed it. All the art you see in the film is Ralph’s real art. It’s not reproductions. I use light to show his pencil marks. It’s very 3-dimensional. That’s what motion control allows you to do. It’s a slow and expensive process, that delivers premium quality film. That is why people watching it can’t work out if they are looking at a feature film or a documentary. It’s actually a documentary made using feature film techniques.

Sophia: You call Ralph Steadman “one of the greatest artistic influences in your life.” When did you first encounter his work?

Charlie: In England, through various publications, I became aware of this amazing artist. Book after book, Ralph’s work was so recognizable and so modern in its own way. As an art student I thought I had come across a modern day master. Ralph will be judged for years to come as someone who is not tainted by time or fashion. His work is consistent and timeless.

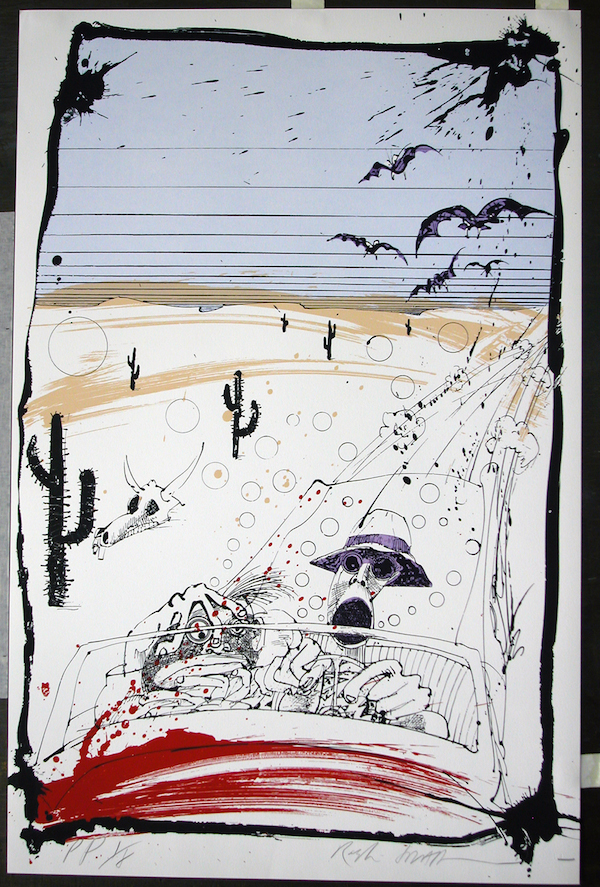

The first time I knew that Ralph was Ralph, was in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The way those drawing were attached to someone else’s writing, yet had their own life. That pairing of Hunter S. Thompson and Ralph Steadman was incredible. They were both complete characters, and yet they didn’t encroach upon one another. Nonetheless, everyone used to think that Hunter did Ralph’s drawings, in the same way that Ralph’s books were so similar to Hunter’s writing.

To come across an artist who kept his own ground in a novel that was swamped with such an amazing character in and of itself, I just knew that Ralph was someone who couldn’t be corrupted by outside influences. As an artist, Ralph was someone that you could follow – much like Francis Bacon or Picasso. Those guys might change their style, but they were always themselves.

Sophia: Fifteen years ago, you made that trip to Old Loose Cort in Kent (1.5 hrs from London) to meet Ralph Steadman for the first time. How did you score that invitation?

Charlie: At art college, I had been fascinated with the process of recording artists’ work. Putting a camera on a blank canvas, the artist would make a mark, then as they would step back to recharge their brush, I would take a frame. I had put together a body of work like this with different artists. I had heard through the grapevine that Ralph Steadman was also interested in filming his own work. So I sent him a badly written letter: “Dear Ralph, I am doing the same thing as you. Can I come and show you my films?” I took a film down and Ralph was like, “Oh, that’s not really what I do, young boy, but I am very happy to carry on this conversation.” So I said “Great!,” and I asked, “Can I put a digital camera above your desk?” And that’s what I did. I arranged with Ralph that if he recorded his work, I would take away the video, shape it, bring it back to him, and talk about what he was doing. He didn’t see much sense in it, but he thought, “Oh, why not give it a bash!”

Then literally every two weeks, he would fill this chip up. He would ring me up and say, “The camera is not working anymore. I’ve finished this.” I would drive down there that day, get the chip out of the camera, put in a new one, and say, “You’re off again, Ralph.” I would take that chip back to my studio, open it up my computer, and there would be two weeks of work — maybe ten-fifteen different canvases, all stroke by stroke, brilliantly recorded.

Ralph loved me taking these films back to him and showing them to him. We would discuss what we had done. It became a very personal, intense relationship. I am the only person that has ever done this with Ralph. And Ralph will never do this with anybody else – because it was not something that he was interested in doing in the first place. He never saw much sense in trying to repackage his work for different medium. But over the years, our companionship became something that Ralph would very much value. I would encourage him to work, he would be rewarded by my excitement about the work. After a while, Ralph would expect me to be there on a regular basis.

Sophia: Do you still record his work?

Charlie: I do. Ralph still has the camera above his desk. I picked up a chip last week. Even though we discussed the fact that “You know, we’re not making another film, Ralph?” “Oh, whatever!” I regularly go down to arrange press stuff and so on with him. We’ve come to a stage where Ralph can no longer travel with us everywhere we go, but we do a Skype Q&A, where you are actually in Ralph’s studio for an hour. He carries the camera around, and he splats things, gets things out of drawers. It is just like my film, on a very scrappy, live basis. Nothing has changed in that studio for the last fifteen years. Continuity-wise, it always works. Ralph almost always wears the same painting jacket. I never had to ask him to put things back. It is exactly as it was. It is fantastic time-capsule.

Sophia: You claim that that trip to meet Ralph Steadman “profoundly affected the way I see the world and the way in which I work.” How specifically?

Charlie: I’ve learned so much from Ralph, from his courage and his ability to not waiver from his intentions. Not that everyday he knows what he is doing, but he is consistent with his output. To make a film over fifteen years, you need that same kind of courage and intentionality. Ralph has taught me, first of all to make the most out of mistakes. Ralph is a fantastic man for being able to make a mess and to pull it back in. The same with my filmmaking process. I have no idea where we are going, but over the time, we’d rein it back in and find the bits that work. Ralph has also taught me not to be afraid of making mistakes. One of Ralph’s favorite sayings, “There is not such thing as a mistake, it’s an opportunity to do something different.” That is exactly how the filmmaking process was.

Lucy: I think also, he allowed you to have faith in allowing yourself to live a creative life. I think that’s probably what you mean when you talk about the “courage.” With creativity, you can’t get hold of anything. It comes from nothing. So to hook your existence on your creativity, that’s a pretty scary thing. To get up in the morning every day and think that you are just going to produce something out of nothing, that’s going to be out there in the world, and it may or may not make any money to feed your family — Ralph does just that, day in, day out. I would say that he has instilled that core trust in you. To just keep going at it. I also think that he has had a profound impact on our whole family because we have raised kids during the time of making this film, quite literally. Our kids are now twenty-two, nineteen, and seventeen. So most of their conscious lives, we’ve been making this film. And they all have that in them as well. It has been a real privilege from that point of view.

Sophia: What is it like working with your life partner as a collaborative team?

Lucy: Quite tricky.

Charlie: There is a lot of: “Time you stop now.” “No, I can’t stop yet.” But basically, it is good. It’s a marvelous privilege to live and work with your partner.

Lucy: To share a project together is an extraordinary thing. Obviously, there are times when it is intense. The role of a producer and a director, they’re not always smooth — and they shouldn’t be. It can be difficult to keep those tensions contained to just the film part of our lives. So, it’s complex. But we are here together, still.

Sophia: What were some of the producing challenges?

[Deep sigh from Charlie. Followed by a deep sigh from Lucy.]

Charlie: Me! I was the biggest challenge —

Lucy: My director.

Charlie: It’s a scrappy process.

Lucy: In terms of producing, I could not have cut my teeth on a more complex project. It is shot on every single format. The audio is recorded on really every sort of format. The music has been put together in really every possible way — from having tracks composed and performed, to having some tracks that we have other artists performing, to some tracks being licensed. Every part of this film is as complex as it could possibly can be.

Sophia: Ralph says, “If you surprise yourself still … you can have a [really] good trip.” How did you surprise yourselves in creating this film?

Charlie: Oh, my God. Obviously having Ralph lead the way — every day was an unpredictable day.

Lucy: I don’t think that there was a single person that we approached that did not want to collaborate on this film. I would say that was quite surprising. That actually is thanks to Ralph and the relationships he has with people. Everyone we approached, wanted to be involved and were happy to offer their time.

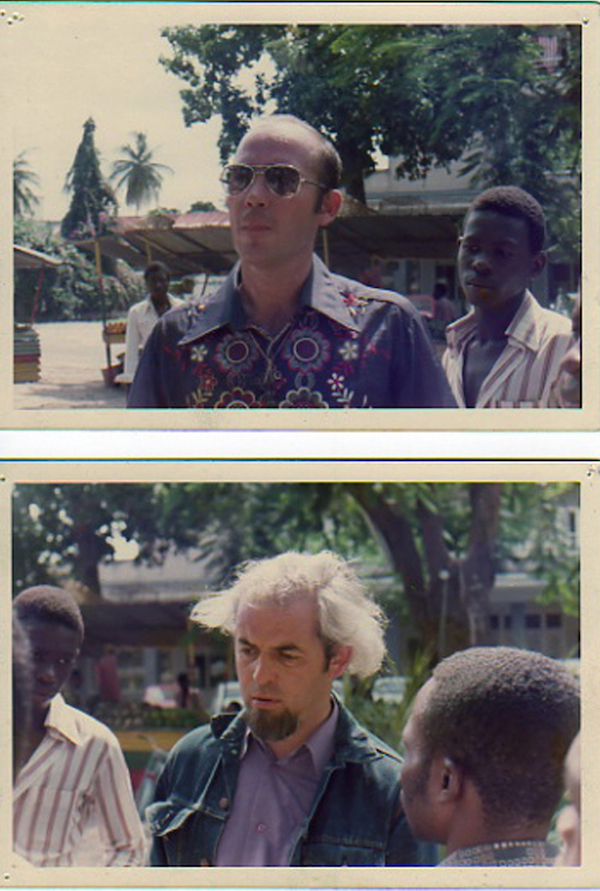

Photo by Lucy Paul, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Sophia: As I was watching the film, I felt like Johnny Depp was a surrogate for you, Charlie. How did you approach Johnny Depp to take on that role?

Charlie: First of all, Johnny is a frame to the painting. Ralph is the art. Johnny is there at the beginning and the end, and all around the edges. Whenever the film is about to run off [the rails], Johnny is there to stop that. I knew that there had to be someone else in Ralph’s studio, apart from Ralph. It was too rich a diet to be in there without Ralph bouncing off of anybody. It wasn’t going to be me. Johnny was the perfect subject to invite in.

Johnny’s connection with Ralph came through Hunter. At the time of his death, Hunter had run himself into debt through massive consumption. There was this danger that all of his estate would be broken up. When Hunter died, Johnny paid for the whole estate and become its guardian. So it was a matter of my producer, Lucy, finding the time for Johnny to become involved. Obviously, to get him to come to the U.K. to be part of the filming was very complicated. Johnny was always ears to the project. Over the years, we would send him clips of the film, Lucy would approach his lot, and eventually, the call came that he was ready to come in. When I put those two together, it was so easy. The conversation just flowed. I just stood back on those days, and they ran their own show.

Photo by Ralph Steadman, Courtesy of Ralph Steadman/Sony Pictures Classics.

Sophia: Your film showcases the first time ever that Ralph’s art has been animated. Can you talk a bit about that process?

Lucy: We had one lead animator, Kevin Richards, who has worked for us for about fifteen years.

Charlie: Ralph was very skeptical at first about animating his work. “Why?! Why do that kind of thing?” he often asked. I knew it had to come to life in a cinematic experience. We spent years in the beginning trying to work out how to animate it. One day, Ralph gave me a clue on how to approach it. I asked him to describe his art for the film, and he said, “Imagine a fly flying down a freeway, and there is a car speeding up the freeway. This fly hits the windscreen of this car and splats. At that moment it’s dead, it’s still, but it’s still got a tiny twitch of life in it. That’s my drawing. That’s the moment that my drawing [takes place].”

So we said, why don’t we just track this fly’s life back a little bit before it hits the windscreen. We cut on the windscreen, but the journey to that windscreen is the animation. Suddenly, it worked. Ralph recognized it. He got the gag. After that, he allowed us to take other drawings and work with them. You see all these animated sequences ending on Ralph’s artwork. We didn’t ever leave Ralph’s art. It was animated within.

Lucy: It was about retaining the integrity of Ralph’s art.

Sophia: Ralph says in the film, “I really thought that if I ever learned to draw to draw properly, I would try to change the world – for the better.” I can really relate to that desire for your life and your work to matter. That theme feels very much the heart of this film.

Charlie: The intention of the film was “to matter.” The intention of the film was to get Ralph’s message out there. My job was to bring Ralph’s message to a new medium. I knew that the integrity was already in my subject. If my art lives forever, it’s because of Ralph’s art that lives forever. I am confident that Ralph’s art will be as fresh in forty years time, as it is now. Even though he made it forty years previous. It was that longevity that I was investing in as a filmmaker.

Sophia: Steadman only sells prints of his works. He does not let go of his originals. He laments, however, that by holding onto all of his originals, sometimes it represses his desire to create yet another. That is a very interesting paradox.

Charlie: Ralph does spend a lot of time amongst art that he has made before. With all this art around, why make more? That has always been a big question for Ralph, “Why am I creating more stuff?” But Ralph is driven. He is still driven by all the injustice in the world. One of Ralph’s favorite sayings has always been: “I try to change the world with my art. And I have done. It’s worse than it ever has been.” That’s how he sees it. The world has marched on in a worrying way for Ralph. So his work always has that bite.

Sophia: What is Ralph working on right now? And what are you both, working on now?

Charlie: Ralph is currently working on a series of books on extinct birds. They are all his own original take on them, and they are marvelous. Last week, he was doing stuff for the New Yorker. Ralph is constantly producing work for publications and his own books. He will be working to his dying day, which makes him the great artist he is.

I am working on a project about London — about many artists in London, actually. Working with Ralph, I became fascinated with the passage of time. Ralph has documented and lived through tremendous changes from when he first started. There was no digital technology, no mobile phones. In the same way that For No Good Reason was made to reflect Ralph’s take on those changes, my next film is about my take on the last forty years of a location in Camden Lock, where I grew up in London. I am using the artists and the people in that arena to describe to my children what’s happened and where we are now. It is a process. It might not take me fifteen years …

Lucy: [sternly] It won’t take you fifteen years.

Charlie: My producer is now correcting me. Ralph has taught me to set off on a project undeterred. Ralph will go to his blank piece of canvas, and he will start, and that will take him to the end. I am hoping that my career follows that example.

Lucy: I think one of the big difficulties for artists in today’s world, there is often this expectation that you know what you are doing when you set out. You meet the producers and the financiers and have to take on whatever they demand. I think it is really important that you don’t put those kind of inhibiting, restrictive stakes in at the beginning. As a filmmaker, I believe that you should be allowed the space to explore, because it is during the process that you discover what you are doing.

“For No Good Reason” Official Website and Trailer.

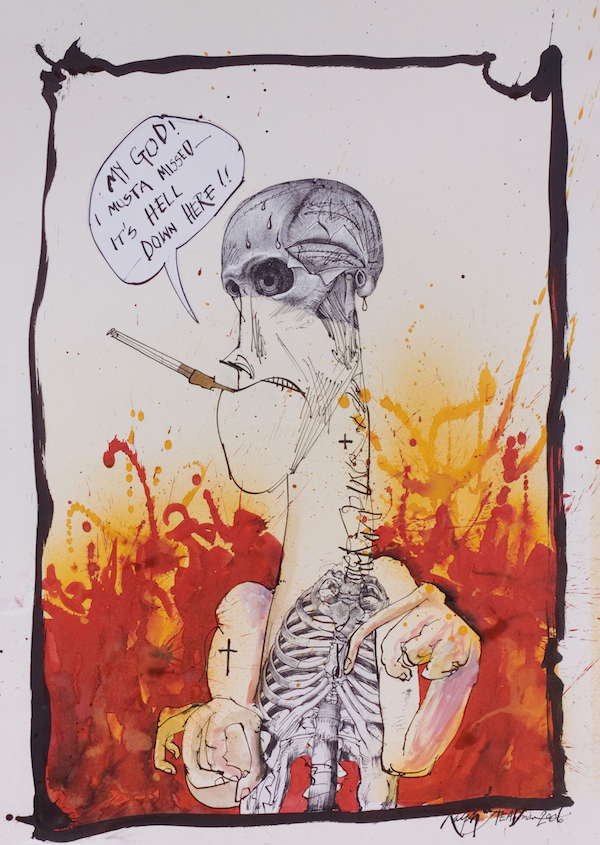

Top Image: Illustration by Ralph Steadman, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.