In the introduction to Grant Hier and John Brantingham’s new flash fiction collection, California Continuum Volume One: Migrations and Amalgamations, D.J. Waldie offers the following diagnosis of Californians: “Californians, because of the way in which their place became Joan Didion’s ‘wearying enigma,’ suffer a hunger of memory as familiar to them as a coyote standing watchfully in the middle of a suburban street or a wildfire burning along a ridgeline.” There is no cure for this problem. The history and fabric of California is a vast and varied one, one that defies definitions and labels. However, Hier and Brantingham do offer something better than a cure; they offer readers an epic first volume of distinctly “Californian” voices that provide an alternative view into the migrations, communities, violence, and natural landscape that have formed and continue to form California.

Upon opening the book, most readers will realize immediately how little they know of the history of California, besides what they have read in their fourth grade history or social studies text books. According to the preface, from Robert Petersen’s “California, Calafia, Khalif: The Origin of the Name ‘California,’” the name “‘California’ derives from a 16th Century romance novel written by a Spanish author named Garcia Ordonez de Montalvo…”. I’ve lived in California over forty years, and had never considered the origins of the name of this state that I love so much. Hier and Brantingham’s collection is a window, actually, multiple windows, into California’s ancient and modern histories. The book sets side by side an offering of voices, some fictional, and some closer to creative non-fictions, that guide us through a multitude of thought-provoking times and perspectives.

Upon opening the book, most readers will realize immediately how little they know of the history of California, besides what they have read in their fourth grade history or social studies text books. According to the preface, from Robert Petersen’s “California, Calafia, Khalif: The Origin of the Name ‘California,’” the name “‘California’ derives from a 16th Century romance novel written by a Spanish author named Garcia Ordonez de Montalvo…”. I’ve lived in California over forty years, and had never considered the origins of the name of this state that I love so much. Hier and Brantingham’s collection is a window, actually, multiple windows, into California’s ancient and modern histories. The book sets side by side an offering of voices, some fictional, and some closer to creative non-fictions, that guide us through a multitude of thought-provoking times and perspectives.

The collection is worth picking up for Grant Hier’s forward about Geronimo’s horse blanket alone. It is clear that both Hier, who is the first (and current) Poet Laureate of Anaheim, and Brantingham, who is the first (and current) Poet Laureate of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, both hold a deep reverence for California and its enigmatic nature. In the initial offering, “For Those of You Who Don’t Understand, That’s What You Call Real Love,” the reader is confronted with a moment on April 29, 1992 where “just as Reginald Denny was trying to stand back up, a single red brick made from high desert iron oxide, lime, magnesia, clay, and sand was lifted high amidst the chaos and rage and thrown full-force from close range, shattering his cranium into more than 44 shards and fracturing his skull in 91 places…”. This beginning story is true, heartbreaking, yet hopeful. Mirroring the book’s subtitle, the piece examines “migrations,” how the brick, which was born in a Riverside quarry, ended up in South Central Los Angeles, and how Reginald Denny also came to be at that particular place; and “amalgamations,” the mixing of people and places that can end up in tragedy but that can also bring about moments of forgiveness and clarity: “Reginald Denny says he knows the people didn’t attack him because they hated him, they did it out of helplessness and disrespect for being disrespected.” Brantingham and Hier offer a broken-down moment in the Los Angeles Riots that is not a news story or an account; instead, the materials and people involved are there before us again, and we are asked to consider and reconsider multiple meanings and possibilities that open up our understanding of this event.

The Los Angeles riots, the Zoot Suit Riots, a child being taken from school to a Japanese Internment Camp, a boy hunting with his father, the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, a woman running away from an abusive relationship—these are the voices that are given a home here. The reader is not told what to think, but is left to make his or her own conclusions. The details are striking and human; they allow us to step inside someone else’s shoes for a moment, to see from their eyes, to live in California in a different time and in a different place. Anyone who worries that historical accuracy may have been lost in the fictionalizing of these events should ask themselves how accurately history itself has been recorded in the past.

In writing this first volume, Hier and Brantingham’s contribution to our understanding of California’s past is significant. In “The Train Whistle,” the woman who is running away from abuse finds herself in the desert, “and when she hears the train whistle, she laughs. To her, it’s like the far off noise of people cheering, that moment when the sounds of all those people yelling together blend into a single triumphant call of joy.” Each voice in California Continuum is a unique reminder of who has stood on this soil before us, but it is also a note that merges with the other voices in the book and in this way becomes a part of the whole being of what California has been and still is. It is in these spaces of encounter that movement stops for a moment, allowing us to re-experience a moment of history, and then continues, not in chronological order, but in a way that momentarily shifts our perspective again and again. According to etymonline.com, the etymology of the word “continuum” is “‘a continuous spread or extension, a connection of elements as intimate as that of the instants of time,’ from Latin continuum ‘a continuous thing,’ neuter of continuus ‘joining, connecting with something; following one after another,’ from continere (intransitive) ‘to be uninterrupted,’ literally ‘to hang together’.”

Hier and Brantingham have created a space that allows all of these voices to “hang together.” It is an action that both men hold important not only in their writing, but also in creating spaces for others’ writing. Brantingham and his wife, Ann, have developed free programs that offer week-long classes in poetry, fiction and art. Hier’s work as a poet laureate has also allowed him a platform through which to bring people together. In speaking of his previous collection, Untended Garden, in an LA Fiction Anthology interview with Red Hen Press, Hier says his work is both specific and universal:

A song of myself, yes, but also a song of the interconnectedness of all life forms, of all that came before, and all that is here now—and of which we are all a part. With no exceptions. And these connections extend out in all directions, and include what was before, is now, and will be after we are gone. All one, really. Which makes separateness an illusion.

The collection does not just bring moments of the past together, but will also help to provide spaces for people to come together in the future, since the authors are donating all earnings from this book to not-for-profit organizations that help create “equal opportunities for everyone to have their voices heard.”

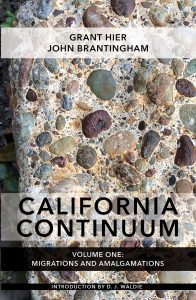

In the last piece in the collection, “E Pluribus Unum,” Hilda decides she has a favorite rock. Her reasoning aptly functions as a metaphor for Hier and Brantingham’s collection:

…because it’s clastic—rocks composed of broken piece of older rocks, and the most common rock found on the face of the earth. She loves that, and loves how each thing residing within it is a broken individual from a larger source, all relocated, all pulled down and smoothed by natural forces, each arriving separately to the same place, each thing becoming bound with others by the finest essence of what came before, all co-existing now as one thing.

Hier and Brantingham help to give California a more egalitarian historical context. In “Fifteen Takes on California,” author and professor David Ulin looks at California through the lens of fifteen words. In viewing California through the word, “Place,” Ulin has this to say:

California as land’s end, world’s end: It collapses underneath the weight of such a reading, as it must. It reveals the limits of our history—demographic history, social history, history of technology, our sense of this place as final landscape, last territory on the continent, where we face ourselves because there is nowhere to turn. And yet, what of its elemental history, its geographic history, which operates independent of our aspirations, as if we were never here? This is the secret story of California, not its instability so much as its implacability, a blank slate upon which we inscribe our dreams.

Hier and Brantingham coax the “secret” story of California out of the shadows and onto the page, where its voices become a network that defines California not simply through its voices, but in how these voices function together. The “blank slate” is not as blank as it once was; the dreams, hardships, and aspirations of the people in this collection ask us not only to face ourselves, but to also face each other.

This collection’s ability to foster empathy is much needed in this time. Flash fiction is known for its capacity for suggestion. Each short piece allows us to crawl into another’s experience. At times we have a flash of recognition, or a flash of anger, or a flash of connection that we were unaware of before. Hier and Brantingham skillfully use words as containers for understanding. These stories become the vehicles by which we discover and hold on to meaning, but they also become the conduit by which change can occur. Readers of California Continuum will leave the collection with a deeper understanding of California and an authentic desire to do better for California, for all those Californians who came before us, and for all those who will come after. I am already very much looking forward to Volume Two.

(Feature image by Alexis Rhone Fancher)