While watching the announcement of Green Book as Best Picture at the Academy Awards ceremony on TV, I saw a platoon of white dudes in penguin suits filling the stage of the Dolby Theater clutching their sacred Oscars. I said to myself: “What the fuck is going on here? I thought that this was a film about a humanistic Civil Rights victory in the The South in the 1960s.” At that point, I had not seen the film, but heard that it had been championed by major Black Civil Rights leaders like Harry Belafonte and Congressman John Lewis. Two days later, I watched it streaming on line.

So what did I see? It was a soap opera about a tough New York Italian guy whose bigotry is transformed into friendship and admiration for his employer, an exceptionally talented Black musician. It’s a lovely, amply depicted sequence of events that should warm your heart and possibly bring tears to your eyes. With an acknowledged racist in The White House, some are apt to see this film’s fictional bigot’s transformation as a cautionary tale that might impinge on the millions who will hopefully see it.

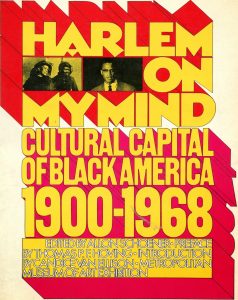

That having been said, I would like to place this film in a historical context with which I am familiar—depictions of African Americans by Caucasians. On January 16, 1969, my HARLEM ON MY MIND exhibition (I was exhibition curator and designer.) opened at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Among Black dignitaries attending that event were: Percy Sutton, Borough President of Manhattan and H. Rap Brown, Chairman of SNCC, Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee, which had organized lunch counter sit-ins across The South. We had a project staff of six: three White males, two Black males and one Black woman. In addition, we had a Harlem Community Advisory Committee of twenty-four.

For several reasons, HARLEM ON MY MIND was exceedingly controversial. Fifty years later, the exhibition remains a landmark event and the book which served as the exhibition catalogue is now in its fourth printing. I see no such enduring history for Green Book. Rather, I see a quick disposal of the film after its first round of showings. Its flagrant disregard for Black film talent will not be overlooked nor excused. Nor will The Academy’s endorsement of a flawed inferior film be forgiven.

In contrast, I shed tears for Spike Lee. He got a token Oscar as one of a team of screenwriters. His first Oscar! How can that be?

He was the first African American film director acknowledged equal status with his White counterparts. He demonstrated that films by Black directors can make money. He was a pioneer in the struggle to overcome entrenched racism in the film industry. Beyond that, he made some remarkable films.

A page from my book, The Italian Americans, appears in Do The Right Thing. It is a recruitment handbill for cheap Italian laborers. One of the film’s cast holds the book open and refers to discrimination against Italian Americans as resonating with African Americans. I was never contacted for permission to use this page from my book. I might have been able to sue for copyright violation, but chose not to do it. I considered this to be my gift to a director whose work I admire.