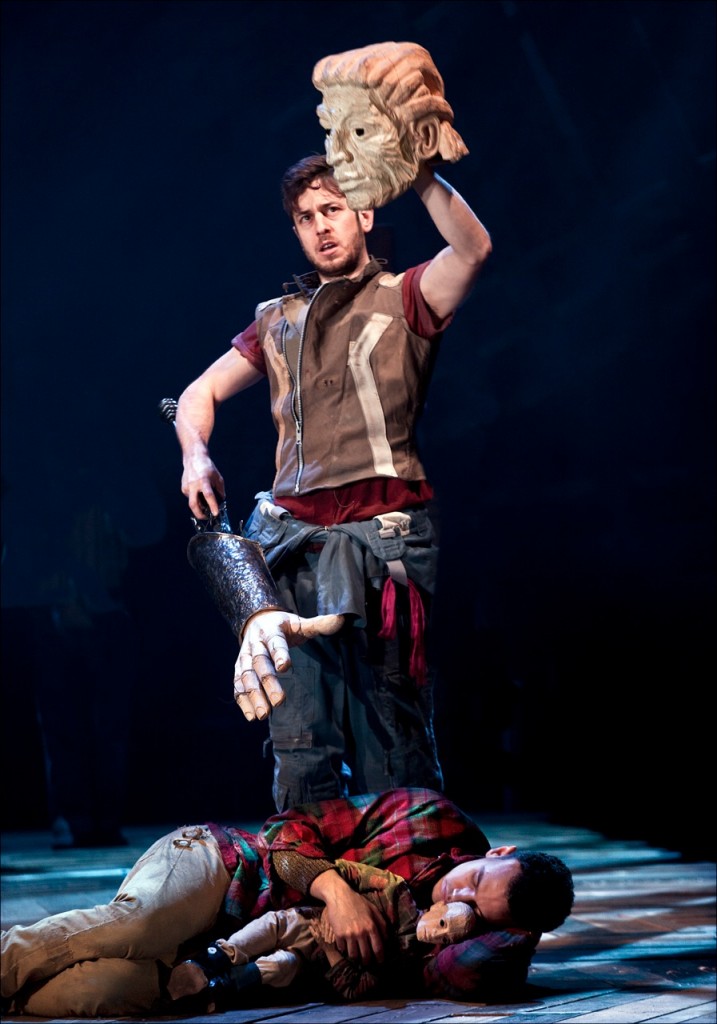

The Handspring Puppet Company guys of South Africa, the fellas who created the remarkable life-size—and rideable—horse puppets for the stage versions of War Horse, are back in town. They’ve created puppets for the Bristol Old Vic’s staging of A Midsummer Night’s Dream opening tonight at the Broad Stage in Santa Monica—from tiny bees and fairies to…well, you’ll have to see the show.

Puppets and masks are as ancient and varied as the people who people the planet. (The puppet is a mask and both aim for the same jugular.) The reason for their enduring existence is simple: puppets and masks are a cover for what we as individuals are hesitant to reveal. They are our alter egos—the bolder ones, the comedians, the outspoken critics and the truth-tellers that we are so often too timorous to be. They reach as far back as pre-historic times and as close as 21st century theatre and digital animation.

If puppetry is thought of as a folk art that found a niche with children’s theatre, it was never historically less than a deeply serious adult form from the start. Its progression in every corner of the world was originated as a component of lay and sacred ritual. It slowly morphed into a form of adult entertainment, while the advent of film (including horror film), television and other digital media, such as YouTube, has only enhanced its acceptance in a wide variety of ways. It now reaches a wider audience than ever.

Puppets are Punch and Judy, they are Japan’s Bunraku, Avenue Q and The Muppets. They are Disney animation, they are the Bread and Puppet Theatre of Vermont, they are Julie Taymor and what made The Lion King the enduring musical that it became.

And they are, of course, War Horse.

They hold us in thrall, never ceasing to mesmerize and ultimately transform. If puppetry still bears the slight stigma of “outsider” status, it also nourishes and elevates the more traditional forms of contemporary theatre. Think too of Edward Gordon Craig, Erwin Piscator, Maurice Maeterlinck, Alfred Jarry, Tadeusz Kantor, Fernand Leger, Lorca, Picasso, along with Robert Wilson, Richard Foreman, Bill Baird, Jim Henson, Philippe Genty and Peter Schumann. Simply google the ones you’ve never encountered before…

Below is an exchange with one of the most recent puppet master to make a splash: South African Adrian Kohler, creator of the puppets in the Bristol Old Vic’s Midsummer production, with some of his thoughts on the subject.

Question: How many puppets are in this Midsummer production and how many people were involved in their invention?

Adrian Kohler: Roughly fourteen. Some are made up of bits that get used by themselves and then come together later as whole units. Workshops with actors and puppeteers were held in Bristol, in the UK, where we explored the notion that “all objects have the right to life.” Then here, in Cape Town, we had a “Dream Team” of six people, that in the end swelled to around ten to get things done.

Based on the outcomes of a workshop I [would] discuss ideas for puppets with Tom Morris, the director—in this case mostly on Skype because of the distance between Cape Town and Bristol. Then [we’d] do a lot of drawings and working drawings that are given out to the team. Sometimes there is no set way to make something. In this case I give the job to someone who needs the challenge, like, “make me this twice life-size fully articulated wooden hand that can pick things up with its fingers.”

The stunning thing is that it’s in the show and has performed perfectly and is heading towards its 200th performance…

Q: Did you wake up one morning and decide: “I am going to become a puppeteer”? Can you provide some background?

AK: No, I was genetically programmed into it. My mother was a puppeteer. I got the bug in the womb. There were “how to” puppet books all over the house which, after a while I could virtually recite by heart. Neighboring kids used to ask repeatedly for shows…

I tried to give it up and studied sculpture at art school. It didn’t work. They said this is an art school, you can’t make puppets here. I joined a local theatre’s puppet section as soon as I graduated.

Q: Your War Horse puppets were extraordinary for their size and strength, allowing grown men to ride them. This adaptation of materials to purpose is remarkable. Do you do it by trial and error or do you know exactly what to use from the get-go?

AK: On account of the above books, I always go to classical puppet construction methods first to see what might be useful with a new problem. No use inventing new joints when someone has thought about them before. But then nobody to my knowledge has had to build a rideable puppet horse before—at least no one who has written a book about it.

First thing to ascertain was whether we could hold anybody up there on our backs. We asked a neighbor to take a chance and sit on a plank balanced between two backpacks strapped to two of us. She didn’t fall off and we found that we could move with her up there. Slowly the horse got built around this basic idea, leaving enough space for movement inside the horse that the puppeteer would require.

New movements were developed for the ears, tails and the curling hooves of the legs. Lightweight but strong materials such as cane and aluminum were used, and the skin of the horse (see-through from the inside) is made of a stretch “power net” so that the actors can respond directly to what is going on around them.

A prototype horse was built, shipped to London, tried out with actors and tested by physiotherapists. Then back in Cape Town the real [puppet] horses were designed and built. From the first small cardboard model to the opening night at the National Theatre it was 18 months.

Q: How do you approach a project? With an idea about puppets or an idea about play and plot? Both?

AK: It seems always to be different. A Midsummer Night’s Dream has the obvious fairies, but perhaps more fundamentally, it needs a concept of magic that a modern audience can buy in on. That’s a nice challenge whether you are using puppets or not. We have adapted other classic plays to a South African context. Because we aren’t writers ourselves [we] take something that works and then set about making it work for us. We have done this successfully with Woyzeck, Faustus and Ubu Roi among others. Animating the inanimate seems to be our primary job and we are always looking for stories and directors who want to work with us.

Q: What variety of materials do you use?

AK: Carved wood is the favorite, but it gets very heavy when the puppet gains in size, so then cane, carbon fiber, aluminum, leather, resin and, heaven forbid, polystyrene all have their uses.

Q: What’s the time lag between deciding on a project and coming up with the finished product, including, of course, the design and construction of the puppets?

AK: I don’t like to rush, but once you know what you’re going to make, it’s six months to a year of construction. Actually, it’s almost never that much and never enough. But then you use up a lot of midnight oil. I’ve never been able to avoid using a lot of that priceless commodity.

Q: How large—or small—are the puppets in A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

AK: From a little bee puppet, that is small enough to miss if you aren’t paying attention to some large—one-and-a-half times life-size—animated statues.

Q: Can you describe the process from start to finish?

AK: Workshops, two or three times; text cutting and editing for ensemble work; puppet design and build; rehearsals that include a lot of detailed puppet sessions. Every day of rehearsal has a dedicated “puppet hour.”

Q: How do you account for the fact—and it is a fact—that puppets of any size and composition almost always make a deeper impression on a theatregoer than live actors ever can?

AK: Because you in the audience put something of yourself on the stage. You have to agree to let the puppet live in your imagination. By so doing you are involved in the creative act of the live performance. Your blood is on the tracks too.

Q: Please talk about anything that you think I should have asked but didn’t….

AK: I think I answered… everything.

***

WHAT: The Bristol Old Vic with Handspring Puppet Company present Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream

WHERE: The Broad Stage, 1310 11th Street, Santa Monica, CA 90401

WHEN: April 3-19, 2014

HOW: Tickets 310.434.3200

Photos credits: Simon Annand