When Walt Disney was still a teenager, near the end of World War I, he volunteered to be a Red Cross ambulance driver in Europe. Arriving a few weeks after the end of the fighting, he stayed in France for almost a year, stationed near Versailles, Paris, and Neufchateau. Then, still besotted by France, he returned home to Kansas City. A few years later, he moved to California and started the Disney animation company with his brother Roy.

A clever exhibition now at the Huntington Library, Art Gallery, and Botanical Gardens makes a visual case that Disney discovered the style for his films on this and later visits to France. “Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts” pairs about 50 works of 18th-century French art with animation clips, scores of drawings, and cels for his films. It also includes renderings for his theme parks, such as Frank Armitage’s nearly 4-foot-wide study in 1988 for Disneyland Paris (top image).

The show focuses particularly on work for three hit movies – Cinderella (1950), Sleeping Beauty (1959), and Beauty and the Beast (1991) – that show the developing sophistication of Disney’s animators. It also demonstrates what a laborious task it was to create cartoon movies in the pre-computer era. In one of the first galleries a visitor sees, a 5-by-5 grid of 24 animation sketches and one video monitor nicely contrast the two-dozen preliminary drawings of a whirling dancer with the roughly one-second animated scene.

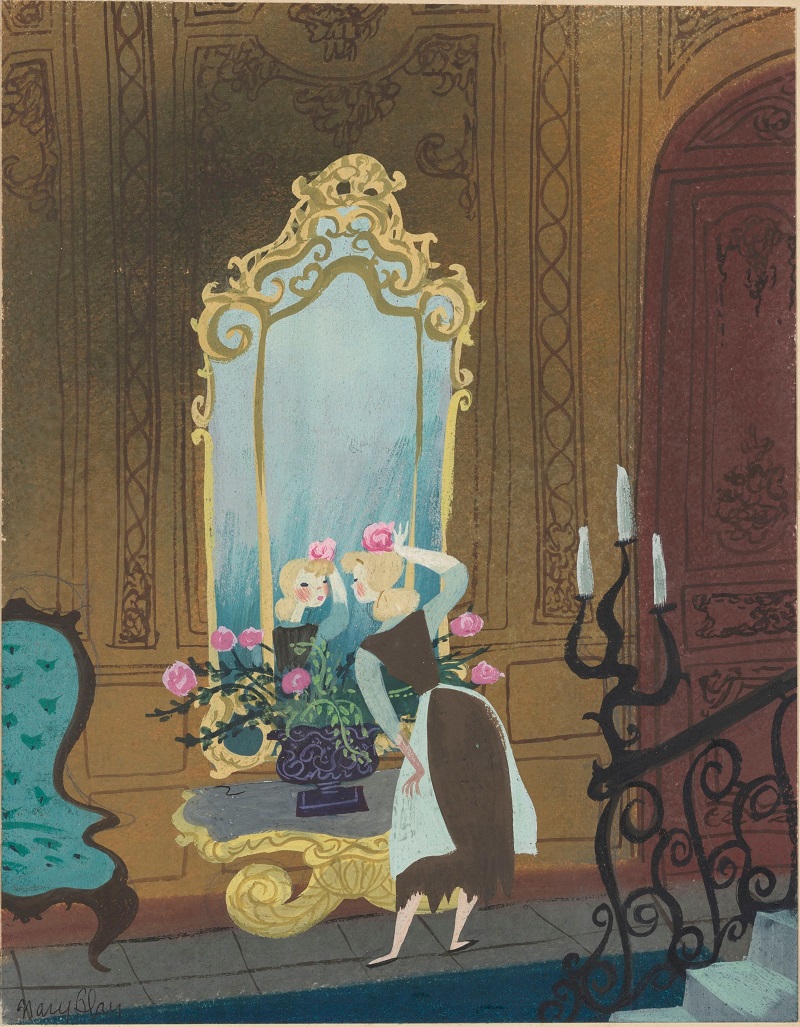

The French influence couldn’t be clearer than in a concept drawing for Cinderella from the 1940s by Mary Blair. In it, the title character gazes into a huge gilded mirror in front of an equally ornate table. Along with a curvaceous chair to the left and the endlessly high walls and staircase to the right, the scene would be perfectly at home for a French chateau, or even the Palace of Versailles.

This attention to detail didn’t come by accident. In 1935, after achieving success with a series of short cartoons featuring Mickey Mouse, Walt Disney traveled again to Europe. From this grand tour – to France but also to Britain, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy – he brought home 335 illustrated books that formed a reference library for his studio back home. (Disney animators also visited the nearby Huntington through the decades for inspiration on 18th-century style, the exhibition shows.)

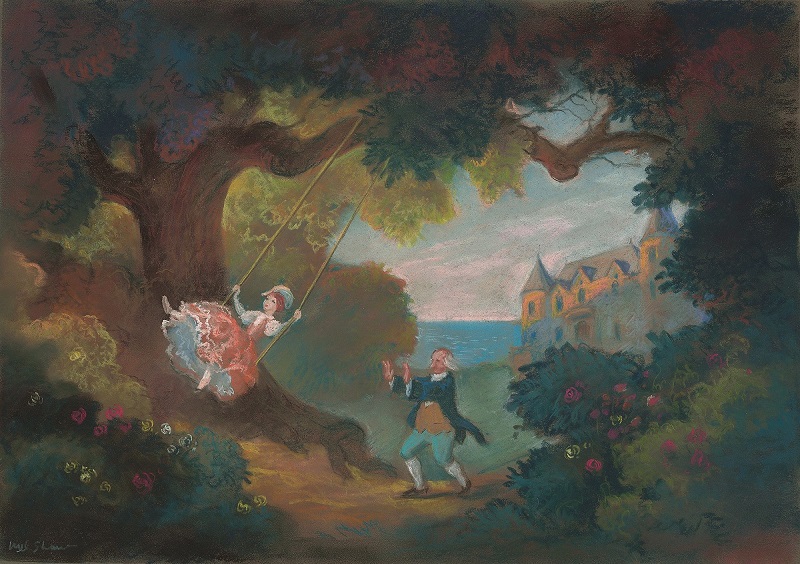

In a pairing of French source material and Disney concept art, Jean-Baptiste Pater’s oil painting The Swing of about 1730, from the Huntington’s permanent collection, is hung next to Mel Shaw’s stylistically similar Belle on a Swing of 1989, for Beauty and the Beast.

In each case, the young woman on the swing wears a flowing, full-length dress and is suspended from a huge old tree above. The man helping to push or pull the swing is outfitted in knee-length breeches and a fancy coat. In the Pater version he’s surrounded by several other family members or friends, while Shaw simplifies the image to two characters. But they’re remarkably similar in their sweetly sentimental moods.

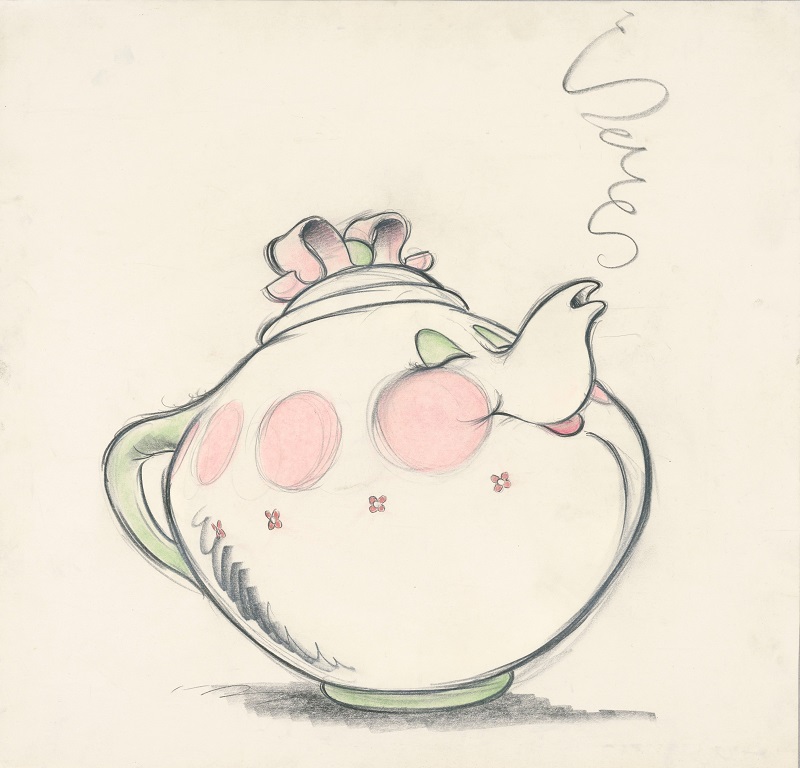

One of the signature styles of the Disney studio is, of course, bringing ordinary household objects to life, such as the bucket-carrying brooms in the Sorcerer’s Apprentice section of Fantasia (1940). The exhibition pairs, for example, a white Sevres teapot from 1758 with a similar teapot character named Mrs. Potts, an animation study that comes cheerfully to life in Beauty and the Beast.

Both teapots are bulbous, bright, and cheerful, the Sevres with blue and gold decoration, the animation sketch with pink and pale green. Both feature unusual handles on top, with blue vegitation on the Sevres and a ribbon on Mrs. Potts. She seems to be taking a nap, or meditating on her good fortune to have such distinguished ancestors.

Another case of a French object inspiring an animation character is clear in the exhibition’s pairing of a gilded 18th-century pedestal clock with Peter J. Hall’s 1989 concept drawing for the character of Cogsworth the butler in Beauty and the Beast. While Hall’s adaptation of the clock’s style for Cogsworth’s uniform – both its shape and its color scheme – is clever and amusing, you can’t take your eyes off the clock.

Attributed to Andre Charles Boulle and on loan from the Wallace Collection in London, the clock’s case is decorated in oak, tortoiseshell, marquetry of brass and turtle shell, gilt bronze, glass, enamel, brass, and ebony. It’s outrageously over the top, a masterpiece of excess, and one of the stars of the show.

Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts runs through March 27 at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, 1151 Oxford Road, San Marino, California. The exhibition was organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Wallace Collection in London, where the show ran in 2021 and 2022. An extensive catalog is published by the Metropolitan Museum and Yale University Press.

Top image: Frank Armitage, Le Chateau de la Belle au Bois Dormant Disneyland Paris, 1988; gouache and acrylic on board; Walt Disney Imagineering Collection; © Disney.