When the artist bears witness to an atrocity, the viewer is called to experience the traumatic, side by side with the artist. Zvika Lachman’s Catatonia transports us to such a moment of co-equal witness. My own access to this monumental work occurred in his studio in Tel Aviv. I met Lachman when I studied at NYU in the 1980’s. When I planned my visit to Tel Aviv in March of 2019, I made arrangements to visit Lachman’s studio, hoping to interview him about his work. It was there on a rainy Sunday, I encountered the immense power of Catatonia (Homage to Géricault).

Lachman explained that the original seed for Catatonia had been a drawing he completed in 2003; he had returned to this subject by creating a series of paintings in recent years. In some of his works, Lachman enters into a dialogue with the Old Masters by re-interpreting their compositions through the lens of his present-day/contemporary perspective. Catatonia illuminates our own era in Lachman’s re-envisioning of Géricault’s 1819 masterpiece, The Raft of the Medusa.

Géricault’s painting documented a maritime atrocity that had occurred in 1816. The Medusa, a French frigate, sank off the coast of Mauritania when Viscount Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys, the ship’s aristocratic, but woefully inexperienced captain, struck a reef in notoriously dangerous waters. As the Medusa began to sink, the captain ordered the ship’s carpenter to build a raft for 150 of the settlers and sailors on board; the captain, the officers, and the wealthy passengers took the only lifeboats. The moment the raft began to knock into the lifeboats, the captain ordered a connecting rope between the two vessels to be cut, and the raft drifted out to sea. The lifeboats made it to safety, but did not send for help. Two weeks later, when another French ship, the Argus, accidentally encountered the raft, only fifteen were still alive, and five died within days. An embarrassment to the French monarchy, attempts were made to cover up the incident, but two survivors wrote about what had occurred as the raft drifted: starvation, dehydration, murder, and finally, cannibalism. Their story became a scandal in France, and inspired Géricault’s most famous work.

Géricault’s painting of this event used a monumental, heroic style, magnifying the impact of the scene, confronting its viewers with the horrors of human depravity. Its subject shocked the French Academy. Géricault was initially deprived of artistic recognition in France, and almost destroyed the masterpiece. But it later became a celebrated symbol of French Romantic and revolutionary political ideals, recognized as a powerful social critique of the class divisions that had played out as the ship began to sink. The Raft of the Medusa now hangs in The Louvre.

Lachman was intrigued by Géricault’s re-creation of the disaster and by the force of its second-hand witnessing. In his decision to create a monumental painting that alluded to Géricault, Lachman’s Catatonia creates an implied referendum on the catastrophes of our own era. During the ten days I visited Tel Aviv, as a member of the online community, I witnessed unfathomable acts of cruelty and horror: a year after 17 high school students were gunned down in Parkland, two surviving students and a parent took their own lives; in New Zealand, fifty Muslims were slaughtered in a Mosque as they gathered to pray; sirens sounded across Tel Aviv, when two missiles struck, breaking a four-year cease fire, followed the next day with hundreds of retaliatory missiles fired into Gaza, in an escalation that threatens ongoing terror through the region. The vortex of Cyclone Idai killed hundreds in Mozambique, leaving two million people without homes; a cholera epidemic now threatens the survivors. From this hell of self-destruction and darkness, Lachman’s painting asks how to make sense of the mangled present.

The multi-dimensional and contradictory movements in Catatonia entrap its figures in a Huis Clos. There is no escape, and the figures are at the mercy of polarizing and conflicting forces, raising questions about human capacity to alter the violence of the world. In an essay on Lachman’s poet drawings, the Israeli poet and critic, Sva Salhoov, described Lachman’s fragmentation of perspectives as a dynamic occurring in a multi-directional entropy, a wild, unraveling complex of contradictory and identical gestures that ceaselessly attract and move in all directions. These multiple perspectives involve us in a moral complexity that asks us to examine our own means of survival, as a battlefield of conflicts assail the figures in this closed, internal space.

During our conversation, Lachman explored the dialectic between the internal and external worlds reflected in Catatonia. He said:

What you see in The Raft of the Medusa is the external world. There is a catastrophe, but in Géricault there is some kind of place you can escape to. The way that I was working on it, it became a kind of closed world. In the earlier work, the apocalypse occurred to me as the collapse of the temple, or Samson’s “Let me die with the Philistines.” A moment of destruction. The entire composition led to an expectation, a resort to an enlightenment from above. The later paintings were shaped by the tension between the catastrophe that is closed, and the intimate interactions among the figures. See, the father and the son in the bottom left. The only help one can find is not outside, but from something inside yourself.

In Lachman’s painting, the point of view comes from within a closed chaos, as if we are one of the condemned souls struggling upward from Dante’s lowest layer of hell. From this Inferno, a tangle of human limbs forms a desperate ladder, but it leads toward a blocking figure, whose ambiguous shadow could be either a savior or judge. Despite the upward movement to escape, an immense column points downward, a phallic force directed toward the parting legs of a reclining nude. A rape. Savage forces have gained power. In Catatonia, Lachman seems to draw us straight into/or: inside the violence. We become actors in the scene, or perhaps jurors, listening to evidence about a crime against humanity. In legal venues, there is an intended outcome, a judgement by which the criminals are held responsible and the innocent are redeemed. But what if the atrocity to which the artist bears witness can’t be named in a court of law? What if the perpetrators include those who witness but remain silent to the injustices that lie in plain view?

Lachman’s Catatonia asks its audience hard questions. What are you capable of? Would starvation, homelessness, flood or fire unmask the violence of your own nature? Are you fated to fulfill the violence of inherited wars in perpetuity? Peering into the screens of witness from a removed aristocracy of global privilege, is your response to the desperate as cold and remote as those who sailed away to save their own skins in that distant boat?

Catatonia cries out to its viewers to find in themselves, a human response to the chaotic and desperate scenes before us. In this act of witness, Lachman demands a kind of moral accounting. Before the apocalyptic present, before the dramatic tragedies of violence and depravity we witness daily, the work becomes a mirror, casting us inward as we confront the question of our own humanity.

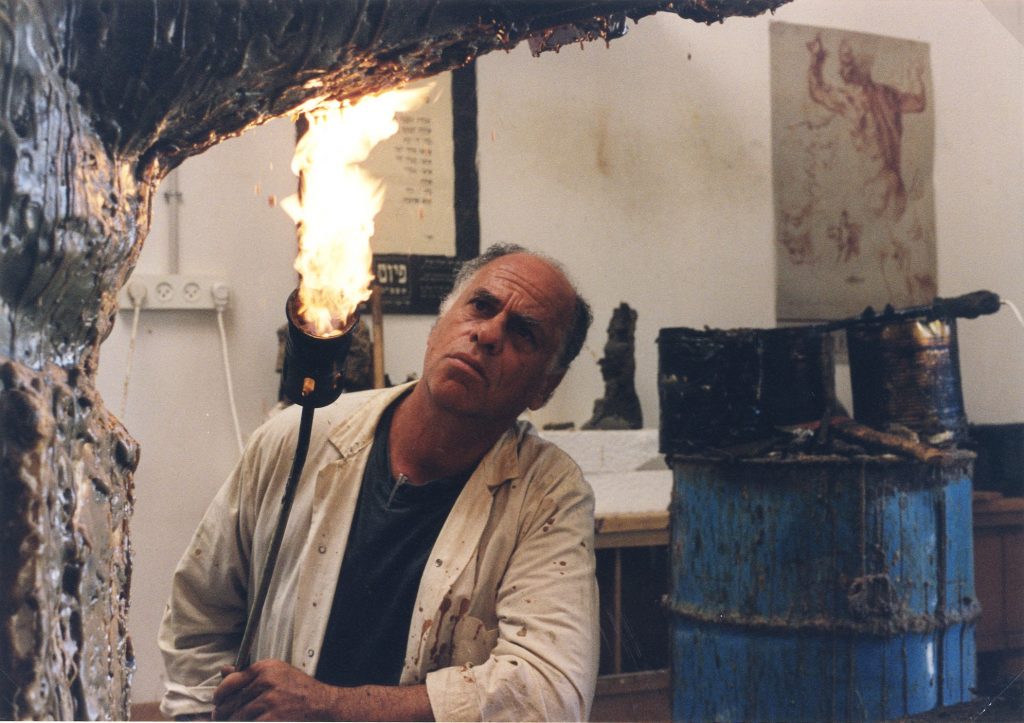

Zvika Lachman’s sculptures are in permanent collections of Israeli Museums and private collectors, and he is the subject of the documentary, One Eye Wide Open: Following Zvika Lachman at Work. In addition to solo exhibitions in Israel, Lachman’s works have been exhibited in group shows around the world, including galleries at Yale University, the Studio School, Parsons, Denver Museum and Boston University. His works represent Human Encounters, the Gaze, the Head, Portraits and Self-Portraits. His present projects are: Genealogy of the Head (sculpture) and Homage to the Jewish German writer, Paul Celan. You can follow his drawing & painting diary in the Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/zvikalachman/