The publicity packet that comes with my advance copy of the American Heritage Dictionary, 5th ed., asks, in very big print, “Will this be the last print dictionary ever made?”

To answer the question, which I interpreted as a warning that we should buy this dictionary before it goes the way of the dinosaur, publishers Houghton Mifflin Harcourt commissioned a marketing survey that found “we overwhelmingly expressed a preference for the print dictionary.”

I resent being lumped with the “marketer’s we,” but my own quickly-mounted unscientific poll confirms that people still own and value print dictionaries, though they greatly prefer looking up words online. But not to worry, AHD’s got that covered too: the new print dictionary will also be available online and as an app.

The welcome screen at ahdictionary.com confirms that once it’s published, “the last print dictionary” will also be available online and as an app.

The marketers at American Heritage also want you to know, “You are your words.”™ It’s the slogan they’re using to promote the AHD, and there’s a website by that name as well, though it won’t go live until the dictionary is actually published. You are invited to come back at that time to “create a unique self-portrait using the words that best define you,” words which will be supplied, no doubt, by the folks at American Heritage. But if it’s true that you are your words, then why do you need a dictionary?

The slogan for AHD5 is “You are your words.” But if that’s the case, then why do you need dictionaries?

Despite the ominous warning, AHD won’t be the last print dictionary, but the real question we should be asking is not whether print dictionaries may soon be as useless to us as typewriters, but whether lexicographers and the dictionaries they so carefully and lovingly compile can survive in a world where word-aggregators offer out-of-copyright definitions for free.

Just as traditional newspapers are losing market share to news aggregators like Huffpo, Drudge, or Google News, traditional lexicographers face competition from sites like dictionary.com, which is run not by lexicographers but by computer geeks. There’s also urbandictionary.com, the lexicographer-free dictionary created by users who simply upload any word and any definition they like. And if you’re really in a hurry, every computer comes pre-loaded with point and click definitions that users can access without ever changing screens.

When it comes to information, computer users don’t worry about the sometimes questionable facts they find in Wikipedia, because for most people, speed and ease of access trump accuracy. They feel the same way about dictionaries, plus most readers think of THE DICTIONARY as a single entity, not one among several competing brands. Many of my students, all English majors who perhaps should know better, don’t actually know which print dictionary they own, and most don’t particularly care where their definitions come from, so long as they are short, easy to understand, and accessible with a click or two.

According to American Heritage’s promotional materials, “There is nothing like the experience of thumbing through a dictionary.” But although the vast majority of my students own print dictionaries, most use them only when the internet is down. And some even prefer to wait until their connection is restored, reserving their print dictionaries not for thumbing through, but for pressing flowers or propping open doors (they don’t hide money in them, as their grandparents did). Or, since they don’t have phone books, because they don’t have land lines, they use the dictionaries as booster seats for visiting children.

Perhaps people are too cavalier about their dictionaries, but it’s also true that the books remain both popular and important. When dictionary publishers announce, as they regularly do, the new words they’ve added to their print or online lexicons, people pay attention, whether they’re critical of the additions or they see them as evidence that English continues to thrive. And when they read on a news aggregator that some politician or movie star used a peculiar word, they look it up online to see what it really means.

Whether we think of specific dictionaries or lump them all under the generic heading “the dictionary,” that book—in print or on the screen—remains our go-to source for definitions, spelling, and the resolution of Scrabble disputes.

I myself own quite a few print dictionaries, including the brand new AHD5. But like my students, I prefer looking up words online. (I’ve bookmarked Merriam-Webster and the Oxford English Dictionary in my browser, and I may do the same for ahdictionary.com). I wonder, though, if there’s an app that will let me press flowers and hide money in these digital dictionaries?

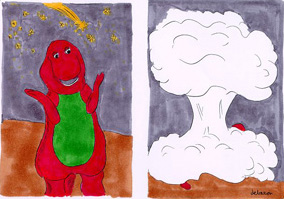

“Barney meets the meteorite” (cartoon by the author). The ominous warning “Will this be the last print dictionary ever made?” suggests that the new American Heritage Dictionary may well be the last of its breed, a collectible, if not a dinosaur, and that you better get yours while they last. But to hedge their bets, the publishers are also releasing the dictionary online and as a downloadable smartphone app. Some enterprising programmer will surely come up with a way to press flowers and hide money in a digital dictionary.

Re-posted with permission from The Web of Language.