Ivory Tower is Andrew Rossi’s wonderfully engaging look at the institution of higher education in this country. The film inspires you to consider – Is college worth the cost? Was my own education worth the cost? Will my children’s education be worth the cost? More than any other single factor, tuition expenses are widening the gulf between the haves and the have-nots. The spiraling costs of tuition are effectively decimating the middle class in America.

Ivory Tower takes the pulse at institutions of higher education from the elite Ivy’s of Harvard, Columbia, and Stanford to the ‘party-central’ campus of Arizona State University; from the desert oasis of independent Deep Springs College to the politicized center of New York City’s Cooper Union College; from pilot MOOCs (Masssive Open Online Courses) developed by Udacity, edX and Cousera, to hybrid experiments (online lectures with in-person seminars) at San Jose State. Ivory Tower anticipates the certain shake up of higher education by information technologies. To the degree that the internet and new technologies have already blown apart the sectors of music, publishing, and broadcast media, they are certain to exert an increasingly profound and potentially disruptive influence upon education.

In the past, educational services were bundled. Young people attended college to gain knowledge, network with peers, and obtain that most valuable of credentials, a diploma. They also attended college to develop skills of value to society, to mature emotionally, to spread their wings independently, to come to know themselves personally and sexually. Higher education has also long served the added societal value of engaging the participation of a labor force that the larger economy has not always been able or willing to absorb. With less and less guarantee that a four year college will lead to a well-paid job, some students are forsaking the traditional college experience altogether and “hacking” their education by moving to places such as Silicon Valley hacker houses, part of the growing “UnCollege Movement.”

Education and its costs are a vital exploration for the vast majority of the population. Ivory Tower is a film that every high school student who aspires to attend college or university and every parent with a kid headed in that direction will benefit from seeing. The film keeps apace presenting interviews with deep thinkers from the most prestigious and interesting of institutions, and is at once entertaining, nostalgic, and educational.

I recently spoke by phone with documentary director, Andrew Rossi, whose film premiered at Sundance Film Festival earlier this year and is now playing in theatres throughout the country. We discussed the making of Ivory Tower, his own education, the corporatization of education, and his attraction to stories of disruption.

Sophia Stein: Ivory Tower is a film that asks “Is college worth the cost?” But moreover, “What price will our society pay if higher education cannot evolve to become economically sustainable?” You are a graduate of two very prestigious institutions of higher education – Yale and Harvard. In your memory of them, were your college experiences life-changing?

Andrew Rossi: They were. My time at Yale was incredibly valuable. I am sure that it benefits from the glow of nostalgia, as it is nearly twenty years ago that I was in college. I formed really meaningful relationships. I studied history, with a focus on intellectual history. That is a discipline that still helps me as a documentary filmmaker very much today. It was socially a lot of fun, but also academically very rigorous. I figured out what I cared about, and what I wanted to focus on in my life. So it was this perfect bridge from adolescence to adulthood.

Key to my experience was the fact that at that time tuition was about $20,000 a year. Now that tuition would be over $60,000 a year. My parents are immigrants, and I’m the first generation in my family to actually go to college in America. They were somehow able to pay for it, so that I didn’t emerge with loans.

Yale is one of the few universities that provides full-need financial aid. (About 1.25% of universities do so.) Students who are admitted to schools that provide such aid are insulated from taking on the amount of loans that 70% of students today are shouldering. Students are emerging with $30,000 on average of loans. So for these students, the calculus is quite different. The burden of carrying that debt, in many cases, constricts their choices in life. When you combine that with trends that we see in the reduction of academic rigor on some campuses and an emphasis on a treating the student more as a customer than a pupil, the question of whether the college experience is worth it becomes problematic.

Sophia: How did you select which stories you were going to tell in Ivory Tower? How did you chose which educational institutions and learning models to feature?

Andrew: We knew that we wanted to represent, as much as we could, the range of higher education experiences. Our goal was to look at schools that have as their mission teaching students versus creating shareholder value for shareholders. So we only looked at non-profits; we excluded for-profit institutions. We wanted to look at the public school experience at a state university. Arizona State is the public school with the highest undergraduate enrollment, so we went there. We wanted to represent unique programs that are an alternative to the traditional colleges. Deep Springs, in the desert of Death Valley, was a great school for us in that respect. It is a real antithesis to the model of the college as a big business with the student as customer. Instead, at Deep Springs College, the students are actually governing the institution themselves and working on the ranch where it is located. The historically Black college, Spelman, which is all female and was formed just a few years after the end of slavery, also depicts a student body that is having an almost spiritual experience, in a school that really inspires its students. San Jose State University is a great representative of the California system devised by Clark Kerr. It was also the site of pilot online classes offered by Udacity. Harvard was the first university founded in America in 1636. As we see in the film, Harvard established the DNA of American colleges and universities constantly striving to become better and bigger.

Sophia: What did you learn in your exploration that surprised you?

Andrew: Right off the bat, some of the numbers that we discovered were really shocking. Particularly the fact that tuition has risen 1120% since 1978 — more than the cost of food or healthcare, more than the rate of inflation. That was a shocker. Another really important number is the amount of student loan debt which is now over $1.2 trillion. Another big surprise was the rate of completion: 44% of students at public universities do not graduate after six years. That is a very troubling number, as well.

Sophia: Professor Andrew Delbanco (Director of American Studies at Columbia University) says: “The college classroom is a rehearsal space for democracy. You walk in with one point of view and walk out with another.” His observation really struck home for me, particularly at this time in history where we see our democracy crippled by the unwillingness of elected officials to engage with opponents across the aisle, to tolerate or grapple to understand opposing viewpoints.

Andrew: One of the things that we hope to convey in Ivory Tower is the historical context. We want to impart an understanding of the role of colleges and universities as a pillar of American democracy and society, and consequently the reason why government has over the years invested funds and its own moral authority into the propagation of more universities and opening the doors to more students. The government exercised its authority in the creation of the Land-Grant universities as a result of the Morrill Act of the 1862, in passing the G.I. Bill in 1944 to benefit World War II veterans and the Higher Education Act in 1965, to create the student loan system. Ironically, that loan system has now become somewhat corrupted, but it originated as a vehicle for students who were poor to be able to have access to higher education.

Sophia: In your film, you document this corporatization of education, this feeding frenzy for universities to outbuild their rivals. University administrators and boards construct the most luxurious “country club” environs, where the university becomes a “social playground for affluent people.” What do you make of that trend?

Andrew: We see in the film that as state funding has declined for universities, tuition has risen. In order for colleges and universities to capture the student loan dollar, they need to create facilities that attract students. It would appear that the most successful ways to get 17 and 18 year olds to apply to a college is to provide luxurious student centers and dormitories, and a range of amenities that have nothing to do with the academic experience.

Sophia: The Cooper Union story is very powerful. That college was founded in 1859 as a tuition-free institution of higher education and you are able to track where for the first time in its history, the President and Board of Directors vote to charge tuition, and the protests that result from that decision. You were in the right place at the right time to capture that story.

Andrew: We were actually in San Francisco when the students of Cooper Union responded to the announcement that tuition was going to be instituted for the incoming class and then decided to occupy the President’s office. We read about that in the newspapers as it was occurring. The moment that we returned to New York, we went to Cooper Union to try to film the students. I met with Victoria Sobel, the student who appears in the film, and we were able to get access into the protest. We also were fortunate to get footage from one of the student activists, Mauricio Higuera, who was shooting literally as the student protestors walked up the stairs in real time to occupy the President’s Office.

Sophia: What inspired you to investigate this topic of higher education as a filmmaker?

Andrew: I’m drawn to stories that are about disruption in institutions that sometimes seem impenetrable or invincible. I think that higher education is an institution in American society that is one of the most ripe for disruption and for rethinking models of its operation that have been in place for hundreds of years. It seemed like such an urgent issue and also one where a lot of change could do a lot of good.

Sophia: I read that the film was commissioned by CNN. What role did CNN play in the creation of the content and in what ways were you beholden to them as patrons of the project?

Andrew: I pitched the project in 2012 to Vinnie Malhotra, who at the time was just starting the CNN Films label. They immediately responded to the idea and asked me to do it. We had a development phase, and then I was in production. I have to say that they were wonderful to work with. They gave me almost complete editorial leeway in making the film and when we were going to Sundance, they were helpful in honing the story. They’ve been great partners.

Sophia: What do you imagine your own children’s futures will hold in regards to higher education?

Andrew: I have a 6-year old and a 4-year old, and although my wife and I are very intent on conveying to them the importance of education and learning as a lifelong pursuit, I hope that one of the trends that will be amplified by the time that they are of age to go to college is a reduction in the stigma if one doesn’t go to college and a blossoming of alternatives to the traditional four year course of study. So that if they told me that they didn’t want to go to college and had a good alternative plan, I would definitely support it.

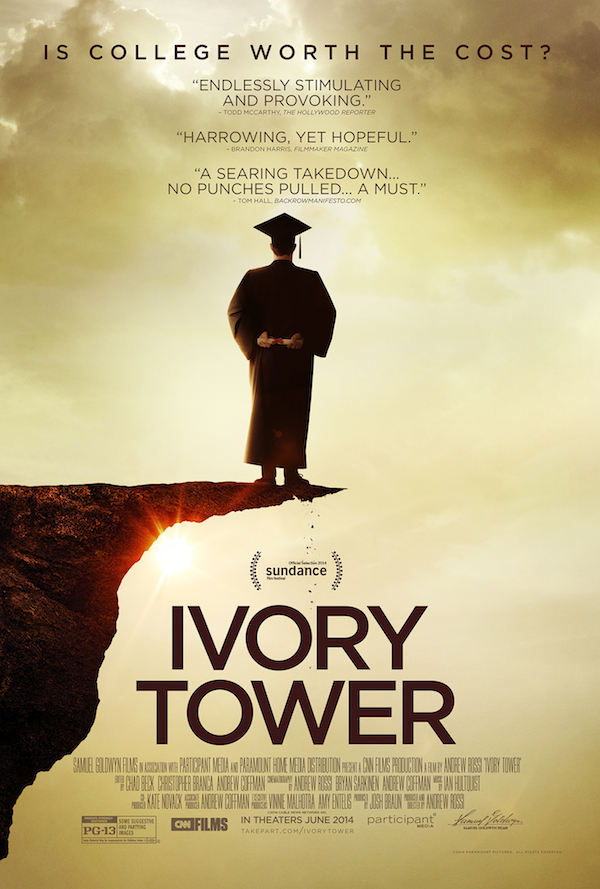

Top Image: Stanford University, “IVORY TOWER.” Photo courtesy of Samuel Goldwyn Films.