I met Jake Eberts through his movies – Chariots of Fire, Hope and Glory, Gandhi, A River Runs Through It, Dances With Wolves – long before I met Jake himself, which was in a booth in the Polo Lounge. Jake held court there whenever he was in LA; he always stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel, where for more than 30 years they kept his clothes on standby for his next arrival.

I was being considered for the job of president at National Geographic Films, and Jake was the chairman. While I wasn’t certain about the Nat Geo’s readiness to be in the movie business, I was positive I wanted to work with Jake. “There’s a lot of potential there,” he said. “You should do this.” So I did.

From that point on, and for the next seven years, Jake and I talked at least 10 times a day. When I say “talked” I usually mean “emailed.” Jake was always traveling – Montreal, Paris, New York, the Middle East, China, LA – but he had the uncanny ability to reply to emails merely seconds after you hit “Send.” His response-time was lightning. He never admitted jetlag, and I remember one time I visited him in the Beverly Hills Hotel, in the patio suite he favored, after he’d been up all night negotiating a deal eight time zones away. “I wanted them to see I’m as tough as they are,” he said with a laugh.

When we bought March of the Penguins, Jake was there, in the lobby of Sundance’s Eccles Theatre, his tall frame towering above the audience members and distribution execs while we assessed who would be our partners in getting the film. He was always generous in giving me and others credit for its success, but without his support we wouldn’t have made that leap of faith.

On the strength of the penguins and our future plans, we embarked on a fund-raise and ultimately secured partnership financing from the UAE. That was only after Jake had visited Abu Dhabi five times, and formed deep and trusting relationships, which was his great strength. Everyone wanted to be Jake’s friend, everyone felt they had a special relationship with him – and, probably, did. I recall an audience with the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, Jake at his right hand, and the Crown Prince grabbing his arm in comradery as if he’d done it a thousand times before.

Kipling’s lines, “To walk with kings, nor lose the common touch,” could have been written about Jake. Another key to Jake’s success was that he had a businessman’s understanding of numbers and deal-making – he practically invented the international pre-sales model of film financing – combined with a true passion for works of beauty, integrity and artistic quality. Who else would have stayed in India for months through the monsoons, wearing a dhoti to endless meetings with government officials, to make Gandhi happen? Who else would have slept in a tent next to principal cast members for the whole shooting schedule to keep Dances With Wolves on track? Who else would have been able to raise enough money for Jacques Perrin’s Oceans, the most expensive documentary every made, and one of the most beautiful?

I left Nat Geo a couple of years ago, and kept up with Jake, “talking” from time to time, and seeing him when we were in the same city. We last saw each other in February at the Beverly Hills Hotel, in the same booth where we first had lunch. He was ill and undergoing treatments, yet relentlessly positive and forward-looking. In the months after, I sent him links to pieces we publish here – poems and music videos, mostly – to which he would respond by email, as swiftly as ever: “Stunning!” “Brilliant!” “I’m sending this to friends.”

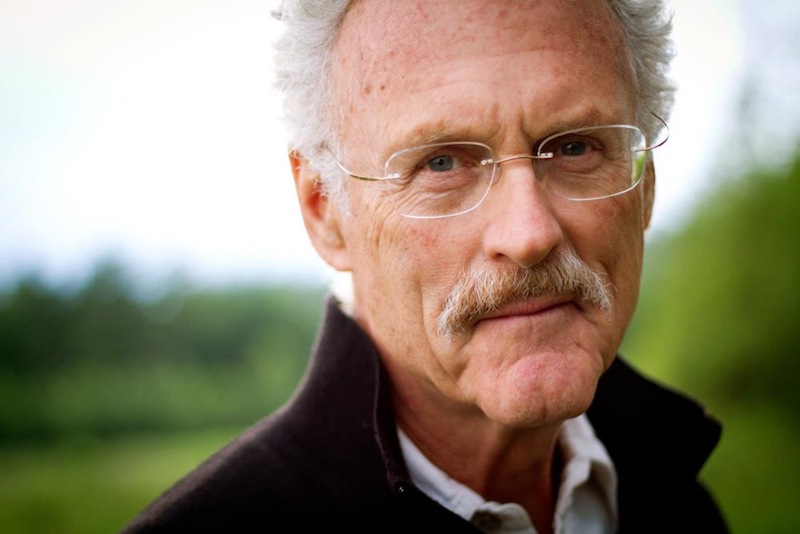

A couple of years ago I visited Jake on his farm, an hour outside of Montreal, where he took me on a tour in his four-wheel-drive. We bumped up a hill, past stands of maple trees and a shack where they did sugaring in the winter. As we curved down the dirt road, he told me to look out my window at a mass of granite the size of a lion.

“That’s going to be my tombstone one day,” Jake said matter-of-factly as it blurred past, and we drove on.