never able to express the culture of their birth

never able to embrace the culture they have come to live in.

Apparently, even before World War II, the Dominican Republic’s long-time dictator Rafael Trujillo had paid the Japanese government for workers who would bring the knowledge, discipline and artistry of farming common in the agricultural fields of Japan. We were intrigued enough to plan a stay overnight. This was possible only because Trujillo had also decided that the region would be good for tourism and had build quite a lavish hotel, which was still standing even if it was in decadent disrepair.

We passed through wondrous jungle foliage and radiant colors from flowers and fauna as well as typical Dominican towns. As the road suddenly curved, a spacious valley came into view with the most startling sight. There, below us, laid out in precise and orderly patterns, were acres of farmlands planed in the ancient style and design of Japan. See from above it was breathtaking: a serene and intricate system of planting usually unknown to this part of the world.

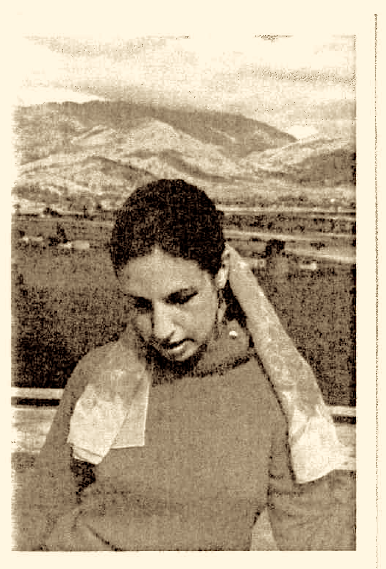

We arrived at the valley floor, parked the car and began walking through the neat rows of fields. Aromas of vegetables and grains filled the air. Now we saw the workers: Japanese women of all ages dressed in their traditional farmers’ clothing. They were kneeling and bending and gathering shaded by the large, pointed straw hat familiar in so many rural pictures from Japan. We began to talk with several of the workers about their history and their life in this remote area. They seemed surprised and delighted to have visitors, if a bit confused to hear a Westerner speaking Japanese. One elderly woman invited us to her home for tea.

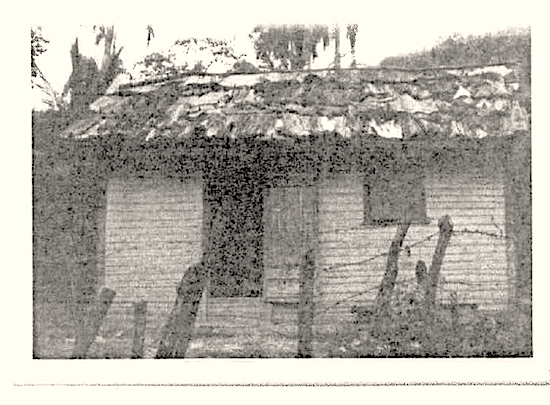

Home for her and for all of the workers was what we would call a shack. For a while, we stood at the door while our hostess tried to straighten her two tiny rooms and arrange her table and the cups for the tea. I could feel how she was trying to recall something long-gone with time; even her Japanese was now a hybrid language. There was no evidence in the rooms of the Dominican culture and, except for an old, lone calendar from Japan showing flower arrangements and beautifully costumed young Japanese women, no evidence of Japanese culture either. The shack was sparse and empty, perhaps reflecting some tradition from Japan but in this extreme case, perhaps a metaphor for what had happened to this woman’s life.

With each new effort to arrange our tea, our hostess seemed to brighten, standing straighter and exuding more energy. At last it was time to sit and drink. We sat at a small worn wood table set against an open window with no screen. As we took the first sips, I looked out at the dirt road, the wild growing trees, the broken, small houses in the rows beyond her window. She told us how she had come to this island, how poor the colony was, how she never had been back to visit Japan. We talked quietly, sipping tea, in this between-place – between cultures, between landscapes, between destinations. She called it a “tea for remembering.”