Social impact documentaries are meant to change the world. They change their filmmakers as well.

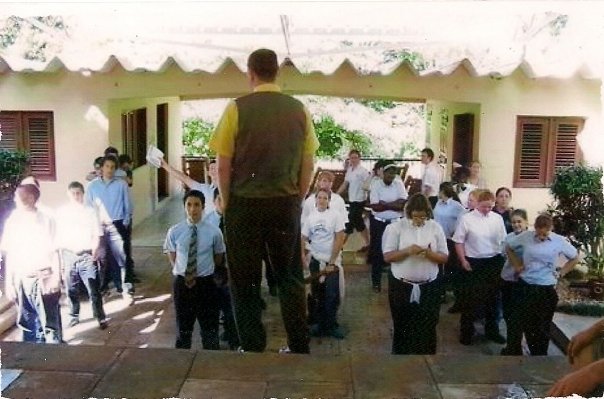

Kidnapped for Christ, directed by Kate Logan, the standout documentary at Slamdance this year, unmasks a Christian reeducation camp in the Dominican Republic where parents forcibly send their teenage children. Ostensibly a place where wayward teens come to know faith and amend their ways, this camp–like over 1,000 other such places–abuses the kids physically and emotionally, Logan’s film reveals. (My review of Kidnapped for Christ is here.)

One month after Slamdance, Logan and I spent a recent afternoon discussing the movie and how she transformed by making it. After making the film while she was a student at Biola University, Logan had to wait five years to overcome legal hurdles, and until one of the main characters, a young man named David, who came out during filming, felt comfortable telling his story in the public sphere.

Adam Leipzig: Let’s start with the film. You have spoken about barbed wire and an armed guard, but I don’t recall seeing those in the movie. Were you prevented from shooting that?

Kate Logan: There was a barbed wire shot, but we didn’t get the armed guard. When we went over there to film, it was clear that we were being shuffled all the way. There was literally this ancient, probably 80-something-year old Dominican guy with a sawed-off shotgun in his lap, that kind of just sat there.

They said it was to protect everyone in there from Dominicans. But I wouldn’t have felt like I needed an armed guard. It was an intimidation factor.

AL: As I was watching Kidnapped for Christ, I kept getting angrier and angrier at the really religious people who were holding the teens captive, abusing them, and feeling so calmly self-righteous about it.

KL: It’s a common reaction.

AL: And yet, you keep your faith.

KL: Shooting the film had a really profound effect on my faith. It wasn’t the only factor that kind of shook me out of evangelical Christianity, but it was the first time I had really been confronted with the people doing really evil things in the religion that I was part of. We’re not super clear in the film, kind of on purpose, whether I stay Christian or not. Four or five years after shooting all of this, I no longer consider myself a Christian. I’m somewhat spiritual, but I wouldn’t put the Christian label on myself any longer.

AL: How do you relate to people who are so fixed in their beliefs?

KL: It’s easy to be like, “Okay, well those crazy Christians that bomb abortion clinics or do this, they’re not like me.” They’re kind of the crazy ones that are giving us a bad name. But what really struck me, like, while I was down there filming was that a lot of the staff members were really not that different from me. A lot of them were young and well intentioned. Some of them were more sociopathic than others, but most of them were just normal, nice people.

AL: That obviously struck you while you were making the movie–how like you the staff members were, and yet how different.

KL: Getting to know a lot of those staff members and becoming friends with them, it was like, okay, well, how was it that they all believe that they’ve heard from God and that they were called here to do this? At the time I believed God sent me here to do this film for a reason. So either I’m right and all of these people who are not that different from me are wrong—and I never could really believe like they did.

After leaving that experience I was never really able to pray the same way, never able to again expect that I was going to actually hear a personal answer from a personal God, because I had seen firsthand how wrong it could go. I never wanted to go down that route, I guess.

AL: Do you now feel that people who have personal communication with God or the divine are delusional?

Kate: I wouldn’t necessarily say that. My mom, for example, I don’t know if she would necessarily consider herself a Christian. Her beliefs on paper probably look more Buddhist. But she is one of those people who definitely has moments where she believes God told her something. It’s never really anything that impacts anyone outside of herself.

So I don’t actually think that people are delusional. I don’t know that God is actually speaking to them. For me, it’s all about the results. If somebody believes God has called them to go feed a bunch of hungry children and they go and do that and they improve the world, then who am I to argue with that?

AL: Then that’s doing good.

KL: By all means, if that person is delusional, than that delusion is working out really well, and I don’t want to criticize. But, obviously, on the other hand, we’ve got people who hear from God and then go kill someone, or go work at a place like this school and abuse kids in the name of believing that they were called to do so. It boils down to personal responsibility. I don’t care what message you think you got from what God. You are still the one doing whatever you’re doing, whether it has a good result or a bad result.

AL: Our spiritual lives are, by nature, so interior and so personal. And while every spiritual tradition has a community focus, there is also this strain of all spirituality which is interior, meditative, hermit-like, and people go to their retreats or go to the desert.

KL: And if God tells them something and says something only they can know, you know, nobody else can really be a witness to that. Unless there is an audible voice in a room…

AL: Making the movie had a transformational effect on you. Your next movie, which you are producing, is called An Act of Love. It’s about a Methodist pastor who was defrocked for performing gay marriages. The gay issue completely turned around for you.

KL: When I went to create the film, I was still of the belief that being gay is a sin. It was like, okay, a good evangelical Christian believes this and I want to be a good evangelical Christian. I remember specifically meeting David and hearing his story. And I never once could wish that he wouldn’t be gay. I never could pray that, God would change him. Just meeting him and interacting with him kind of changed my point of view without me even necessarily wanting to.

Once I confronted this new reality, I could no longer believe this whole thing anymore. I kind of struggled theologically when I got back to Bible college in trying to make the Bible say something different to me. The reality is it’s so vague. In the Bible, with the passages that allude to homosexuality, people can read them whatever way that they want.

AL: You had to decide who you wanted to be.

KL: If at the end of the day I wind up being wrong about this, I’d rather be on the side of loving people, basically, and tolerating them. At the end of the day, if I die and God is like, “Oh, well actually being gay was a sin,” I’d be like, okay, of all the things I could have done, that is not a big deal.

Kickstarter video from ‘An Act of Love,’ the next doc Kate Logan is producing.

AL: What do you tell other documentary filmmakers who come to you for advice?

KL: You just have to hustle. Even the people who are really successful, still you always have to hustle for everything, for your funding, for the favors you need, for the people you need to work with you. If that doesn’t sound like something you want to do, then maybe just do little short documentaries, because it’s way too much work to do it if you don’t love doing it. You really have to not just love it, but have the determination to, like, go through all the shitty, shitty times when it’s not fun. It’s not comfortable, but it does get really rewarding when you can finally come through on the other side.

To support Kate Logan’s next film, visit the Kickstarter link: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/kateslogan/an-act-of-love-the-story-of-rev-frank-schaefer

Top image: Director Kate Logan.