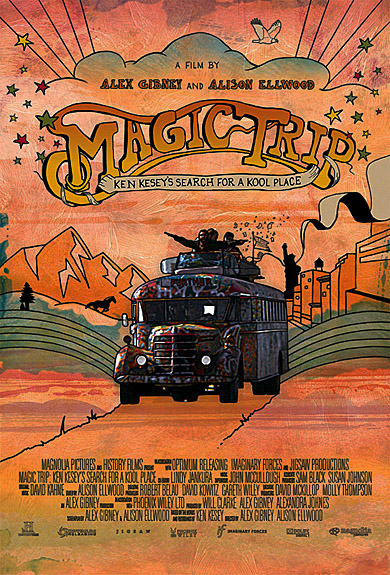

Magic Trip, a new film by Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood, tells the story of novelist Ken Kesey‘s 1964 road trip across America in a painted bus with a troupe of fanciful hippies and legendary beatnik Neal Cassady at the wheel.

This bus trip was immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s 1968 bestseller Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which is also currently in production as a Gus Van Sant film (this will presumably come out near the same time as the long-awaited film of On The Road, which means two major Hollywood films featuring Neal Cassady’s driving skills will hit the screens at the same time). Magic Trip, a modest and straightforward documentary, has at least one claim to authenticity over the eventual Van Sant work: it presents the actual film footage produced by the camera-wielding hippies as they drove across the country in 1964.

The film gets off to a good start, emphasizing in the early scenes an important point that has sometimes been forgotten amidst all the psychedelic Wolfean hype. When Ken Kesey conceived this crazy trip, he was one of the most celebrated and promising young novelists in America, and the bus trip was initiated as an audacious literary experiment above all. It’s hard to exaggerate how much potential energy the young Stanford-educated novelist held in his hands after the success of his 1962 first novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The other hot writers of the moment were Philip Roth, John Updike, Norman Mailer and Joseph Heller, and Cuckoo’s Nest had placed Kesey directly in that class.

But something kept the Oregon kid from strutting around in a suit and embracing conventional literary stardom, and he would risk (and, ultimately, lose) his reputation on the set of adventures to follow. Magic Trip emphasizes the fact that Kesey’s second novel Sometimes a Great Notion was entering its pre-launch publicity phase just at the moment that Kesey decided to travel very noisily across America in a colorful bus; indeed, the bus trip was Kesey’s publicity push for his new novel.

The fact that Kesey must have envisioned his adventure as a literary gesture is often neglected, though it may be the most remarkable fact of all about his much-discussed Furthur/Acid Test scene (well, the fact that the Grateful Dead emerged from within this scene is remarkable too). I have no idea what exactly Kesey was thinking when he got his big idea for the bus trip (other than “let’s go have some fun”), but it’s clear that he was aiming for a big California-based American movement, a new Chautaqua, a mobile version of the previous century’s New England Transcendentalism.

Magic Trip sticks mostly to the script familiar to anyone who’s read Tom Wolfe’s book. There are LSD freakouts, Barry Goldwater jokes, visits to the home of young Larry McMurtry in Texas and an anti-climactic reunion between Neal Cassady and a morose Jack Kerouac at a New York City party. As always when recounting the Kesey/Electric Kool-Aid legend, the psychedelia aspect is a bit overstated in this film. I like to think that the psychedelic drugs were less central to the actual experience as envisioned by Kesey and his partner-in-crime Ken Babbs than they became in the Tom Wolfe legend, and I also suspect that the main appeal of all the LSD tripping for Kesey was not to explore the boundaries of consciousness so much as to induce chaos and fearful vulnerability among his fellow travelers, so as to allow him to wring the maximum emotional reaction from each player in his twisted tale.

Magic Trip is a satisfying retelling of the famous story, and I won’t be surprised if Gus Van Sant’s version turns out less satisfying, once it hits the screens. I do wish that Magic Trip told us more about Kesey’s later works and adventures, like Twister, a controversial play based on The Wizard of Oz that he developed gradually during the last phase of his life. How did Twister fit into the big picture of psychedelic West Coast transcendentalism? Maybe we’ll need yet another film, a third one, to someday explain this part of the legend.

Re-posted with permission from Literary Kicks.