Before discussing a bunch of poetry books I want to dedicate this essay to Lewis MacAdams, the poet and activist who started the Friends of the Los Angeles River in 1985-86. Lewis passed on Tuesday April 21st at the age of 75. He was an important mentor to me. I met him in 1999 at the Los Angeles River Center at an event he was reading at with Gary Snyder and Mike Davis. In the years to come we did quite a few events together, took a few walks along the River and spent some time on a few rooftops in Downtown Los Angeles. I’m too sad for the moment to say much more, but I have written several pieces on him over the years.

In March of 2018, I wrote this long essay about him on this site and it highlights his long career and the park named after him along the Los Angeles River. In 2013, I wrote this essay for KCET. Here’s an audio poem I wrote for Lewis before that. His long career bridged poetry and politics. Over the years we did a lot of readings together. Two of the most memorable were in 2005 at Union Station with Wanda Coleman and in 2001, we did a guerilla reading out in front of Pink’s Hot Dogs on La Brea. Among the many brilliant tributes to Lewis in the last 24 hours, this one by his son Torii MacAdams hits the hardest. Torii is a music journalist and his prose carries on the family’s literary spirit. Thank you Lewis MacAdams, we’re not done.

12 Books for National Poetry Month

If quarantine has been good for anything, it’s been catching up on reading. Piles of poetry books stack on my desk year round and in the last 6 weeks I have finally had a chance to bring it down to a much more manageable size. Here’s a roundup of as many poetry books as I could get into one column. Many of these following books are brand new, but a few are from within the last year to year and a half and I finally have had a chance to slow down and talk about ‘em.

The Portrait of Self As A Nation

By Marilyn Chin

Oh, how trustworthy our daughters,

how thrifty our sons!

How we’ve managed to fool the experts

in education, statistic and demography””

We’re not very creative but not adverse to rote-learning.

Indeed, they can use us.

But the “Model Minority” is a tease.

We know you are watching now,

so we refuse to give you any!

She defamiliarizes stereotypes and also talks a lot about her own family, how her parents named her, her divorce and long career in poetry. The poem was one of the most electrifying beginnings I have ever heard at a reading. Chin had on an AC/DC shirt and her dynamic personality definitely translated on the stage like TnT. Her next poem, “Blues on Yellow,” was equally engaging. She followed that up with “25 Haiku,” and there were members of the crowd reciting along with her. In between poems she shared stories and her perspective. A memorable sentiment she shared echoed in my brain for days after the reading. The statement was, “we carry our ancestors’ music with us.”

I showed up at the reading with her 2018 book, A Portrait of the Self As a Nation and followed along poem by poem with her set as she announced each one. This book is her Selected Poems and she was definitely sharing her Greatest Hits. In the book’s Preface she states, “I see myself as an inventor of a fusionist aesthetics, of bilingual and bicultural forms. For decades I have been toying with the Chinese-American quatrain, stringing beautiful and subversive jewels into fractured necklaces.” She also created the sonnetnese, a hybrid poem combining the sonnet with the Chinese lyric. Another form she enjoys writing is what she calls “bad-girl haiku.”

Chin is fearless, happy-go-lucky and deeply thoughtful all at the same time. The poems work well on the stage and the page. Other really memorable pieces she shared were “Identity Poem #99,” and the final poem of the night, “Black President.” She offered advice to young writers and when someone asked her about specific references in poems and using other languages within your work, she said she no longer tries to explain things. She laughed and said, “Let them look it up on Wikipedia.” Chin left the crowd empowered and signed a lot of books before the night was over. She was so compelling that nobody wanted to go home. I highly recommend her Selected Poems.

Two other poems of Chin’s in her book that are really well known but were not read at Cal State LA are “Brown Girl Manifesto, One of Many” and “Brown Girl Manifesto (Too)”. In the former she asks a lot of great questions and sets the record straight: “Who is this “˜I” that is not the “I’?” “The speaking subject is also the lyric poet: am I making art or am I only producing material for your ethnographical interest?” Chin is courageous and shows what’s possible for the poet who’s not afraid to go there.

Letters to a Young Brown Girl

By Barbara Jane Reyes

Her “Glossary of Terms,” sets the record straight. This excerpt from her definition of Pinoy exemplifies the veracity of her poetics: “You know what annoys me? People who won’t see the through line from Joe Bataan to Bruno Mars. You ever wonder about the sound of a poet rappin’ with ten thousand carabaos in the dark? You ever eat fish and rice with your hands, off Styrofoam plates, in a hole in the wall, south of Market Street?” Reyes connects the dots across generations of Pinay Poetry and its part of why she’s become an icon to up and coming poets across the country.

Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry

By John Murillo

Meditating on confessionalism, epiphany, prosody, negative capability and contemporary American poetry, Murillo breathes in the boulevard. The opening lines of “Mercy, Mercy Me,” offer a stunning portrait of his serious skills and empathetic capacity: “Crips, Bloods, and butterflies. / A sunflower somehow planted / in the alley. Its broken neck. / Maybe memory is all the home / you get. And rage, where you / first learn how fragile the axis / upon which everything tilts. / But to say you’ve come to terms / with a city that’s never loved you / might be overstating things a bit.” Murillo is a poetic marksman.

Animating Black and Brown Liberation

By Michael Datcher

This book of essays offers an innovative analysis on literary giants like Gloria Anzaldua, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Wanda Coleman, Kamau Daaood, Toni Cade Bambara, Cherrie Moraga and Ishmael Reed. Datcher shows how Black and Brown community organizing can be amplified by creative cultural production. He shows the connection between off the page activism and writers that practice praxis. Melding theory with concrete examples the book begins and ends with specific instances at literary events. The opening section, “Liberation Vibrations,” spotlights an intergenerational community forum held at a poetry reading in Inglewood in 2013 that discussed Trayvon Martin and the school to prison pipeline. Datcher asserts that “American literatures are lighthouses that can show a way out of no way. American narratives can illuminate liberatory possibilities.”

This book of essays offers an innovative analysis on literary giants like Gloria Anzaldua, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Wanda Coleman, Kamau Daaood, Toni Cade Bambara, Cherrie Moraga and Ishmael Reed. Datcher shows how Black and Brown community organizing can be amplified by creative cultural production. He shows the connection between off the page activism and writers that practice praxis. Melding theory with concrete examples the book begins and ends with specific instances at literary events. The opening section, “Liberation Vibrations,” spotlights an intergenerational community forum held at a poetry reading in Inglewood in 2013 that discussed Trayvon Martin and the school to prison pipeline. Datcher asserts that “American literatures are lighthouses that can show a way out of no way. American narratives can illuminate liberatory possibilities.”

Datcher’s discussion of literary theory is grounded in his deep connection to the poets he writes about. Datcher was the Workshop leader for many years at the World Stage in Leimert Park. His reflections on the World Stage’s cofounder Kamau Daaood reflects his understanding of the griots work. “Daaood juxtaposes joy and sorrow, hope and despair, in ways that are often surprising and surreal,” Datcher writes. “The poet’s surrealist oeuvre has been informed by Los Angeles’s surreal juxtaposition of ethnic diversity and ethnic segregation, extreme wealth and crushing poverty, and progressive racial politics and virulent anti-Blackness.” Datcher offers equally accurate assessments of Wanda Coleman, Audre Lorde and Gloria Anzaldua. Datcher shows how these writers are not just poets of witness but emissaries “uniting the scars to make something beautiful.”

A History of African American Poetry

By Lauri Ramey

Pontificating on the work of Jayne Cortez, Lorenzo Thomas, Will Alexander, Douglas Kearney, Evie Shockley, Harryette Mullen, Erica Hunt and Marilyn Nelson and going back to not just Phillis Wheatley but Lucy Terry and Jupiter Hammon and other lesser known African American poets from the 18th Century, Ramey shows how a pattern of neglect by many scholars has created gaps in the canon. Dozens of anecdotes and lesser known but equally important poets are featured throughout the text. This is not a Top 40 breakdown or a parade of more popular poets, Ramey does a beautiful job of spotlighting trailblazers like Fenton Johnson, Welborn Victor Jenkins, Michael Harper, Cladia Rankine and Toi Derricotte. The book’s spirit is about demonstrating how “Afircan American Poetry holds an inextricable role in reflecting and defining American identity, in addition to its ability to inspire world poetry and serve as a source of literary and cultural inspiration.”

Everything Must Go

By Kevin Coval

Coval is not afraid to turn the lens on himself: “i was born here / but haven’t been in some time. / my grandfather grew up a few blocks / from where I’m dizzy with smoke. // what does it mean when we appear // the children of white flight.” The book’s subtitle sheds further insight and also offers a nod to the seminal urbanist Jane Jacobs, “The Life and Death of an American Neighborhood.” Coval offers odes to the waitress, the tamale man, the dive bar, the old bowling alley, the men on the avenue, the gallerist, the incense man and apartments that he used to live in. He “knows the names of everyone,” and honors them in these poems. This is a great example of making the personal, political and universal.

Everything Seems Significant: The Blade Runner Poems

By Jan Bottiglieri

This unique collection of poems circles around the movie Blade Runner. The imagery is cut cinematically. Poem by poem isolated moments from the movie are highlighted, explicated and sprinkled with dialogue and famous lines from the movie in italics. Aficionados of the 1982 SciFi classic will recognize the references. “My mother! I’ll tell you about”¦” My favorite section of the book are the final eight poems, Bottiglieri calls them “Character Ghazals,” because they are each about a specific character and they not only use lines said in the film, the repetition of the last word at the end of every other line hammers the point home powerfully. Each one is precise and really well executed. The piece about Roy Batty is titled, [I want more life.] The final four lines of the poem demonstrate how well the form works:

This unique collection of poems circles around the movie Blade Runner. The imagery is cut cinematically. Poem by poem isolated moments from the movie are highlighted, explicated and sprinkled with dialogue and famous lines from the movie in italics. Aficionados of the 1982 SciFi classic will recognize the references. “My mother! I’ll tell you about”¦” My favorite section of the book are the final eight poems, Bottiglieri calls them “Character Ghazals,” because they are each about a specific character and they not only use lines said in the film, the repetition of the last word at the end of every other line hammers the point home powerfully. Each one is precise and really well executed. The piece about Roy Batty is titled, [I want more life.] The final four lines of the poem demonstrate how well the form works:

Who named me Roy? What kingdom: death or life, Fucker?

Kiln-crazed vessel into which you poured life, Father.

Rain-smeared, stripped bare better to adore life, I falter.

Memory chains/unchains us. I want more life, Father.

Mowing Leaves of Grass

By Matt Sedillo

Dancing in the Santa Ana Winds

By liz gonzalez

Nuclear Shadows of Palm Trees

By Nikolai Garcia

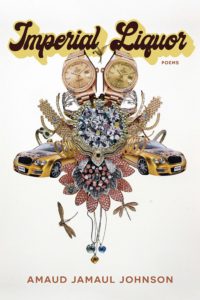

Imperial Liquor

By Amaud Jamaul Johnson

Similar to Jenise Miller, Amaud Jamaul Johnson grew up in Compton. Though he now teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and has won fellowships with the MacDowell Colony and Cave Canem, Johnson’s poems capture the ennui of the 1980s in the Hub City. Douglas Kearney warns on the back cover, “Sip this fire slowly.” John Murillo uses an epigraph from Johnson in his book reviewed above and the characteristic they both share is intense lyricism and formal dexterity. In the piece, “LA Police Chief Daryl Gates Dead at 83,” Johnson writes, “And the deacon board smoked. / And the economists saluted Reagan. / And the police called it an economy of dust. / One meteorologist predicted / a low–pressure system in the abdomen.” Johnson is a poetic alchemist and in this collection he spells out the redemptive metaphysics of his aesthetic.

Similar to Jenise Miller, Amaud Jamaul Johnson grew up in Compton. Though he now teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and has won fellowships with the MacDowell Colony and Cave Canem, Johnson’s poems capture the ennui of the 1980s in the Hub City. Douglas Kearney warns on the back cover, “Sip this fire slowly.” John Murillo uses an epigraph from Johnson in his book reviewed above and the characteristic they both share is intense lyricism and formal dexterity. In the piece, “LA Police Chief Daryl Gates Dead at 83,” Johnson writes, “And the deacon board smoked. / And the economists saluted Reagan. / And the police called it an economy of dust. / One meteorologist predicted / a low–pressure system in the abdomen.” Johnson is a poetic alchemist and in this collection he spells out the redemptive metaphysics of his aesthetic.

Conclusion

If you are looking for some new poetry in your life, look new further than the books above and if you don’t know about Lewis MacAdams, look him up. I’d like to close this account with the last 5 lines of his poem, “The Voice of the River.”

At the center of itself

the River is silence,

and that’s where I come in:

with the sounds in my head

and the words in my heart.

(Featured photo of Lewis MacAdams by Malakhi Simmons)