Crashing the Gates of the Art World

You live in a city surrounded by outlets for art: galleries, museums, and private collections. Publications and email blasts arrive in a continuous stream to trumpet one fabulous, provocative or groundbreaking show after another. You could spend your whole life attending them.

There’s only one problem: you’re an artist, too. A new one, at that.

How are you going to get anyone to pay attention to you? It might be an age-old problem, one every artist experiences, but that doesn’t make the question any easier to answer.

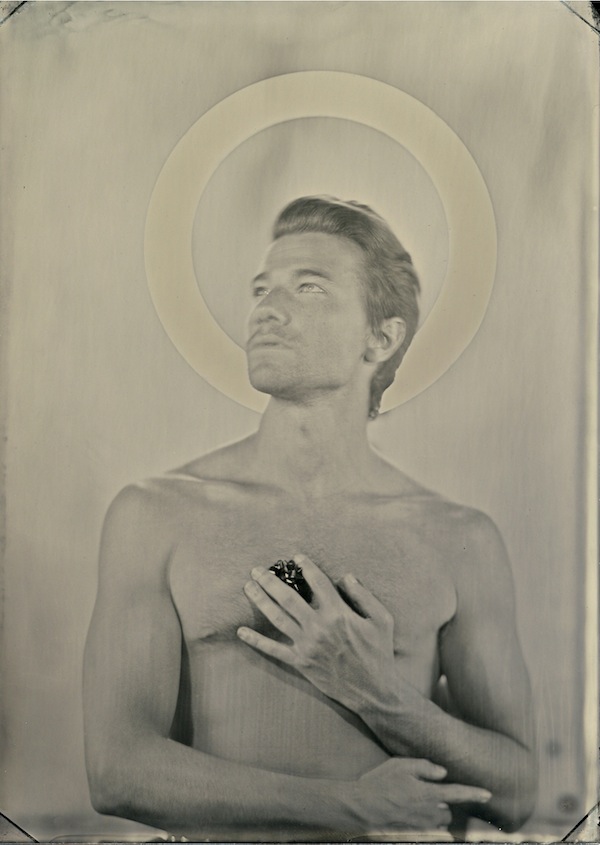

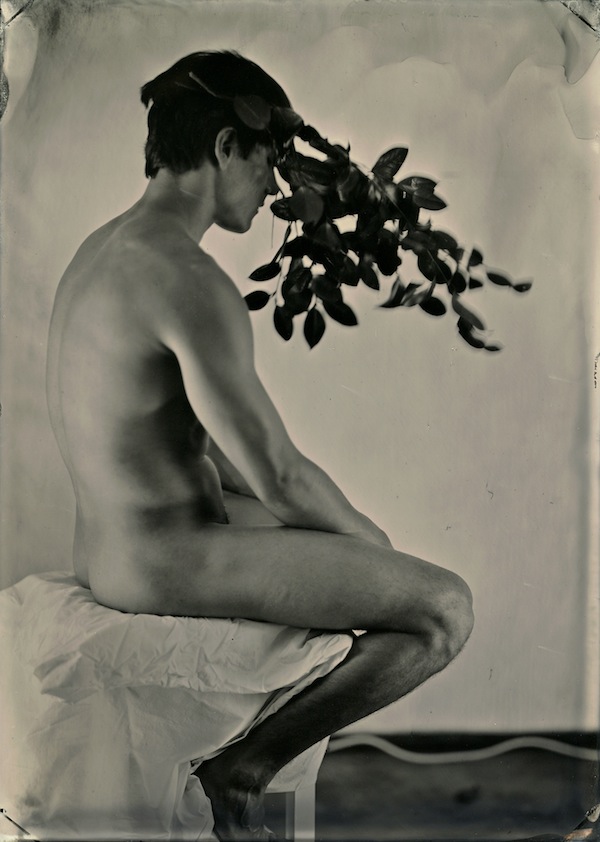

Matthew Finley is just back from another visit to the hardware store. He enters his photography darkroom (a converted garage) with stacks of metal plates and panes of glass. As an artist whose passion is the nineteenth century wet-plate photography technique of tintypes and ambrotypes, his physical materials are more akin to that of painters and sculptors when it comes to storage. The one-of-a-kind photographs take up space and can’t be stored on a hard drive.

“I want to get my work out so people can see it because it helps me avoid feeling isolated, and it helps me connect to other people,” he says, “but some days you just want people to buy something so you can make some room on the shelves.”

Besides space, the glass ambrotypes especially require broad, even lighting. Setting them out just anywhere on a street corner or in a rented booth at an art fair denies the viewer and the artist the best experience. In Finley’s case, location impacts the art itself.

Courting The Gatekeepers

“I’ve spent four years knocking on doors at galleries, participating in group shows, and offering pieces for charity fundraising,” Finley says, only a few days before his first, solo pop-up exhibit goes on display in the heart of the Culver City Arts District in Los Angeles. “Anything to show my work, even when I’ve had to compromise on having the best conditions.”

At forty-two years of age, Finley is still a newcomer to the world of fine art, having switched his artistic focus from acting in television and commercials to photography. Emerging artists face a puzzling contradiction as they search for exposure. There are numerous opportunities to show their work in public settings through community events, educational institutions and the internet. However, most of these venues reach precious few eyes and, if an artist is trying to make any kind of living, even fewer collectors. Galleries and their coveted mailing lists are the gateway to where art and commerce merge.

“Especially with the kind of photographs I take, seeing them on an internet catalogue decreases their power. You can never recreate the experience of seeing them in person.” His photographs capture an ethereal quality that evokes ancient statuary and mythic ideals. “That effect happens because you’re seeing light come off the object itself, not a picture of the picture. You need people standing there. They have to show up, and galleries are where that happens.”

Finley approached numerous galleries seeking representation. “I always got good response. Polite, sometimes eager. But then the hammer drops. They can’t entertain another artist for a couple years, at least. Or they only deal in ‘blue chip’ work (established artists, read: those whose work sells).” But Finley doesn’t blame them. “It’s a challenge to build relationships with gallery owners because you both know what the other person wants. They have their guard up. They’ve probably seen a lot of questionable taste slide out of those portfolios under someone’s arm. But if you can get past that step, the relationship is a key one to have.”

In some ways, the time spent pounding the pavement has redounded to his benefit. His body of work increased, expanding its depth and giving him plenty of material from which to create an event.

“I realized one day that I was surrounded by overwhelming evidence on my shelves that a show would work, aesthetically. It just needed a place to happen. So on the advice of an experienced friend, I decided to do a pop-up show of my own.”

Pop or Flop

Pop-up galleries have steadily increased in popularity, driven in large part by street art namesakes like Banksy or Shephard Fairy. Many spaces have become de facto permanent galleries as a result, and have the same gatekeepers to navigate. Finley realized he was going to have to do it all himself. Find a venue, make it appropriate for viewing the work and market the event. It would have to be personally financed. He would have to go into debt.

“I was willing. I was committed. I gathered a small group of friends and we set about the project. We were almost ready to use a dental office or second-hand clothing store as a venue when I decided to try a long shot.”

Finley re-approached gallery owners with a new attitude. “Doing this as a pop-up show, I feel like I got to take some of the power back. I approached them with a mindset of, ‘This event is going to happen, would you like to be a part of it?’ I didn’t feel at their mercy like I did when I was just submitting for representation and asking, ‘Give me a chance’”.

He met with immediate response. A gallery owner with a prime space looked at the work and heard the proposal—a sharing of investment and a sharing of profit. “They responded to the work, but also to the fact that I was ready to put everything on the line. We skipped that awkward step of ‘What can you do for me?’ and started a relationship. And I feel like whether they sign me after this show, we will continue that relationship and I will be able to use them as advisors on future projects because they’re very good at what they do.”

A lot of work remains. With limited resources, small compromises must still be made to frame the delicate tintypes. “But I feel like we’ve eliminated the big ones. The work will be seen in its best light. I hope to make back the money I have put into this show. More than that would be icing.”

It’s still a chore to get people out of their houses, to fight the traffic, and to show up. Social media is its own puzzle, and it takes trial and error to distinguish between what drives people to actively participate in an event and what merely ‘spreads the word.’ Finley seems excited at better understanding it. “I’m really interested in finding out from people who attend how they heard about the show. What am I doing that connects with them? Is it more form, or content? Is it purely the images or was it a friend’s recommendation?”

He’s also preparing for the comedown. One show, no matter how successful, does not sustain an entire career. The space on the shelves in the garage is still there in case all the work has to come back and wait another day to see the light. But even the process of preparing this event has yielded good things: new ideas for future collections and relationships he can build on.

“There is no book out there that can tell an artist exactly which steps they should take on their individual journey. All the platitudes apply: be persistent, be creative about your work and your career, and try to be okay with being poor! I try to learn from others and apply it as best as I can in my situation.”

But having a solo show in a perfect venue is definitely a milestone. “It feels like my first, real introduction as an artist to the world. My friends and my community will mix with the gallery’s collectors and a whole new audience I’ve never been able to reach. I have gone about it in my own way, but it has turned out even better than I had planned.”

Matthew Finley’s debut show will be at Hinge Parallel Gallery in Culver City, Los Angeles Saturday, Sept. 13 from 6p-9p.