On the bank of a harsh western lake, a lithe and muscular being dances, clothed in nothing but mud.

“It was a kind of evolution piece,” says Paul Langland, describing one of the first solos he performed in Boulder, Colorado. After running in widening circles until the mud washed off, “shiny and nude, I then disappeared over the edge of the bank. Off to conquer the world, I guess!” he concludes with a characteristic chuckle.

Nearly 40 years after Mud Dance (1976), it seems that he has done just that. Paul inhabits a prosperous artistic world of distinct, interrelated territories, whose borders are often porous. In addition to being a mercurial dancer, Paul is also an accomplished singer, choreographer, and collaborator. He has worked alongside many of the men and women who pioneered New York City´s downtown performance scene in the ´70s and ´80s, from Steve Paxton to Meredith Monk. Today, he continues to collaborate and create new performances, which have been presented in both the United States and Europe. He is a master of creating dance “in real time,” and of the art of improvisation.

Examining his career is to enter American contemporary performance, past and present. While literally dancing with history for much of his career in contemporary performance, Paul describes the atmosphere of his early days in New York as “pure enthusiasm.”

“There was a real spill-over between those who danced for fun and those who were more serious,” he said. “This created a loose and free-wheeling atmosphere,” a refreshing sensibility which remains a signature in his work.

On 29 March, the Brooklyn Arts Exchange (BAX) Arts & Artists In Progress Awards will honor Langland with its 2014 Arts Educator Award. The accolade is more than apt: for more than 30 years, he has been one of the core faculty members at the Experimental Theatre Wing at New York University´s Tisch School of the Arts. He has nurtured and influenced hundreds of performance-makers, many of working professionally in dance, theater, music, television and film, and more.

“One of my central goals is that my students find their unique voice as improvisers and choreographers,” he says. “This value comes from my visual arts background.”

Graduating with a BFA in visual art from the California College of the Arts in 1973, Paul says that, when he is dancing or choreographing, that he “imagines staging like a composition for a painting.” He goes on to note the frequent and intimate relationship between dance and visual art, particularly amongst the first generation of post modern choreographers in New York.

“This is one reason I connected so deeply with some specific performing artists such as Mary Overlie, whose Six Viewpoints Theory starts with the examination of space,” he explains. “Also Meredith Monk, who is always thinking of lighting and spacing as an essential aspect of any production. And Ping Chong, also a visual arts graduate, who often approaches his work like a moving canvas.”

Working with these and other influential figures like Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, Barbara Dilley, and Anna Halprin, Paul’s emerging exploration of performance mirrored his experiences in art school: an emphasis on working alone on various projects or tasks, in order to find his own individual voice. “Ironically, being a dancer,” he admits with a smile, “it took me a while to find motion as a core inspiration, rather than shape and space.”

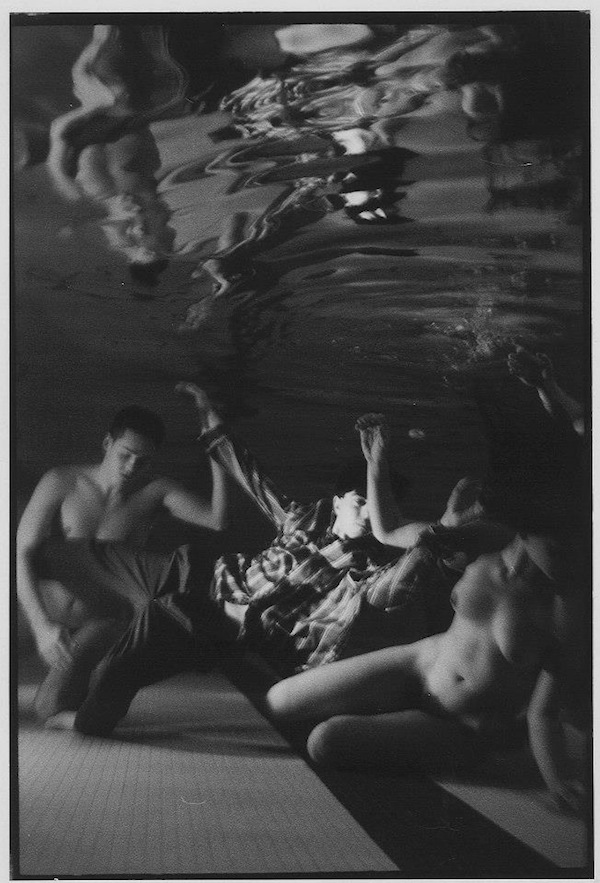

Steve Paxton changed all that. “I was very good friends with Curt Siddall in high school in Amherst, Massachusetts, who was in Magnesium (the first showing of Contact Improvisation at Oberlin College, in 1972). Curt introduced Contact to me, and I loved it. I initially thought it only as a sport,” he recalls fondly.

This improvisational duet form, where dancers explore movement by sharing weight and physical contact, had a profound influence on Paul. “Contact continues to be a constant in my life. It first brought to me a love of motion and dancing with others, and gave me a very positive experience of working as a group, sharing ideas, performances. This newfound love of collaborating helped ‘seal the deal’ that I would go into performance.”

Just as the dance was growing in importance for Paul, Contact was also quickly spreading across the globe. “I was lucky to network with the early group of Contact practitioners in New York during the 1970s,” Paul says. These included Daniel Lepkoff, Nina Martin, Diane Madden, Randy Warshaw, Stephen Petronio, and Robin Feld. In 1983, they formed Channel Z, an improvisation ensemble based on Contact.

Simultaneous to his explorations in dance improvisation, Paul began working with Meredith Monk. After being invited to perform in Chacon (1974), he became a member of The House Foundation for the Arts for the next 11 years. “I seem to flow between voice, theater, and dancing in performance,” Paul confesses. “Meredith was a huge influence in giving me practice to enable various modes of performance to exist in the same work.”

“Meredith created and directed those pieces with some collaborative input from the company members,” he continues. “Her work’s careful attention to visual aspects, careful timing, costumes and lights…Meredith´s pieces have an imagistic and visual depth.”

Anne Hammel, a fellow cast member in Monk’s Quarry (1976), lead to an introduction with Allan Wayne, another teacher that would prove instrumental in providing Paul with a richer understanding of movement. “Coming into the world of dance late as I did, I knew I needed more technique than Contact, yoga, and other improv practices,” he says. “I loved Allan’s classes right away, especially the way he combined classical ballet alignment and placement with energetic work, stretch, and strength training.”

After his sudden death in 1978, Paul invited his fellow students to continue dancing and practicing this work at his loft on Greene Street. Organically this became a class, and in less than two years Paul was teaching Allan Wayne Work throughout Europe, Canada, and the United States. This caught the attention of choreographer and colleague Mary Overlie, who was still relatively new at NYU’s Experimental Theatre Wing program, created by Ron Argelander in 1975.

“Mary hired me as an adjunct at ETW in 1983,” Paul says. “One thing lead to the next, and I have been a part of the program ever since. Allan Wayne Work is a core component of my classes there. I use it as a technical warm-up, and find it to be a great choreographic tool. The choices that come out of this Work are initially felt and experiential, rather than created visually.”

Whether onstage or in the classroom, Paul fluidly moves across disciplines, and creating pictures with sound, motion, and shape. “I have no rules about how I choreograph or collaborate,” he shares. “Each project, either my own or working with others, feels unique.” Nonetheless, collaboration–in multiple manifestations–seems to be a thread that runs through the fabric of his career. With frequent colleagues Overlie and Wendell Beavers, their improvisational performances originate from “worlds” based on known images that they create together. Jungle Breath (1988), created and performed with Daniel Lepkoff, emerged from the two singing and sounding together after many years of dancing in Contact Improvisation. In Normal Kansas (1991), Paul deconstructed William Inge’s play “Bus Stop” into a sprawling dance/theater performance.

The approaching BAX Award ceremony inspires Paul to reflect on the past 30 years as a teacher as well as an artist. “In 1983, ETW was still new and raw,” he says. “There was great enthusiasm, fear, excitement, and chaos all around us. When I started teaching, I was 32. I had a lot of high energy, and was moving constantly in class, out of class, in rehearsals, everywhere.”

Paul believes he is a better teacher today, much more efficient. One of his key values is “celebrating the wisely-crafted vision of the individual,” a principle he upholds onstage as well as in the classroom. He is particularly motivated when he sees his students get engaged, start finding their own value and solutions in the context of what they are doing in class. One of his most important teaching tools is “learning how to let students bring the work to me,” he says.

Economically and artistically, New York City today is certainly different than the one Paul encountered over 40 years ago. Yet his experience has also forged a practical resiliency, maybe even a cautious optimism. “Every generation faces challenges,” he affirms. “When I came to NYC in 1973, the city was in bad shape, jobs were poor or scarce, and paying for life here was very difficult. So even though the city is ever more expensive, artists always seem to figure out a way to stay and revitalize the performing world here.”

“Of course I would like for all university graduates to have no student loans,” he goes on. “Of course I would like entry-level performing jobs to pay better. New York may still be the center of the art world, but it is also getting expensive! This is hard for artists starting out. And there is less space for studios and theaters, and what space there is is expensive.”

He concludes by saying: “I think the biggest challenge facing artists is to have the courage to embrace their own individual vision in the face of artistic, monetary, and social pressure to do otherwise. I am happy any time anyone encounters success, but it’s also important to remember the core inspirations that drive us to be creative artists.”

“Sometimes it’s difficult to stay in touch with these core inspirations when in the thick of the brawl of life,” Paul admits. “I hope that I bring that to my own work and to the creative life of my students. The rest of it will happen, and this generation is different than mine. I trust this generation.”