Reading Lauren Camp’s new book of poetry, Took House, felt like momentarily living within a piece of art, a collage perhaps, where the only thing I had to be at the moment was curious. It was a unique experience for me, who usually wants to pin down meaning, to feel so comfortable with these poems that required me to stay suspended among them. The book begins with “Appetite,” a poem that is set apart at the beginning of the collection, ushering the reader into an immersive reading experience: “the heart was a stipulation, the shade / of her hunger, his palm on her marrow. It is the largest / muscle and she let it / take over, she let it” (1). One of the subjects Camp continually explores in this collection is appetite. The desire to read is a kind of hunger, and this poem ushers the reader into becoming aware of her or his own desires. We want to know more about these poems, and they are so layered and compelling, that they also allow us to be taken over; we, like the speaker in the poem, “let it.”

Camp’s prior career as a visual artist infuses the poems with the material of art – paper, color, canvas, stroke, so that the moment of words on page is something layered and wonderful in which we get to live inside. It is within this collision of art, words, form, and moment, that we are able to see the world through multiple lenses. In “Leather World, This Bird, This Sky,” Camp writes, “and a raptor flies / crooked through its mandolin language. / Suddenly everything verified: cloud without end” (7). The birds that populate the collection, the raven, hawk, owl, eagle, are raptors. Raptor derives from Latin, rapio, meaning “to seize.” These are poems that allow us to both seize and be seized; sometimes we are the raptor, doing the taking, and sometimes, we are the taken.

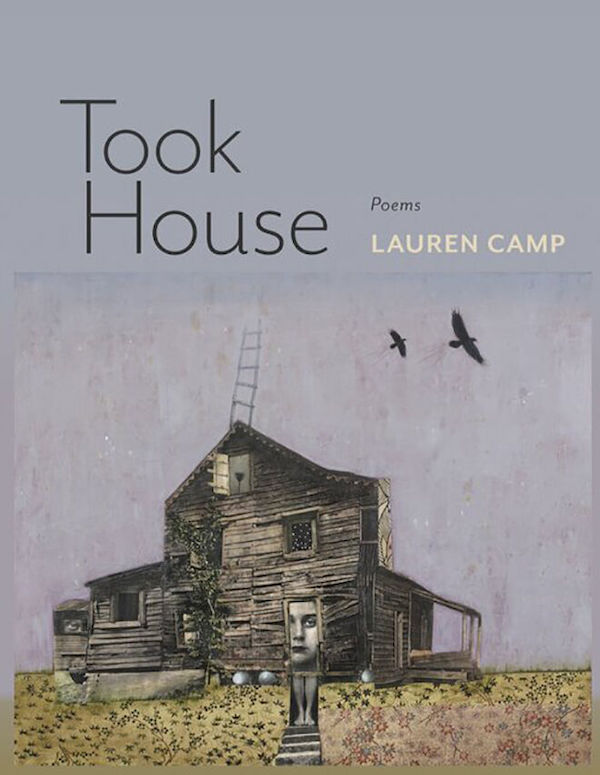

The title of the collection, Took House, is intriguing. The cover art, “Nest,” by Suzanne Sbarge (2005) depicts a house that is dilapidated and curious, a face in the doorway, two legs rooting themselves into the ground, a single eye in one window, a wash of stars in another, a wine glass of something (wine perhaps) in the uppermost window, three eggs underneath as a kind of foundation, and a ladder leading from the roof into the atmosphere, evoke the idea that in having this book of poems, we, too, have somehow “took” this house. But, we have also been “took” into this book house. The idea of a house, or “nest” implies something more temporary than “home,” something to be lived in for now.

Camp layers the concept of the temporary into the poems in Took House. I found myself thinking of Derrida’s concept of différance, where we can only make meaning within a continuum of ideas — we can only make meaning through differences, so that meaning is continuously deferred, since it always relies on the next piece of information. Take Camp’s poem “Fluid,” where she writes, “Forget about thinking; / we were spoonfuls / of liquid. We left one container / and entered another: a glass to a glass” (50). The containers of these poems, like the rooms in the house on the cover, are always being taken. They are always being entered and filled, and they are always temporary. We, the hungry reader, also go from glass to glass. We are the raptor again, for a moment, taking in our latest kill. Consider Camp’s poem “Common Raven”: “And now, the gorge— / the eye, skin, leg. As tires move by, / your endless chewing. / It seems like rage, but it is only hunger” (58). These are poems that remind us how of insatiable we can be.

Camp’s poems are also full of the desire to fill the house, the glass, the time. Several ekphrastic poems, poems inspired by art, speak to how art is one of the ways humans reconcile the instability in our lives and in the meanings we make. One of these ekphrastic poems, “Tar Painting,” was inspired by Judy Tuwaletstiwa’s “TEXT: BLOOD/EARTH,” a multimedia piece. The poem states, “Art was everywhere tethered to walls. / Alice served salmon with a crisp crust. / I drank the gin-clear water and agonized about forks.” Art arrests life, momentarily, capturing it, transforming it into something we can hold in our hands. Part of our hungers, as humans, are our obsessions. We decide on some things like what to eat or drink, and have no control over others, like what we might “agonize” over. Later in the poem, the speaker tells us, “Without prying, I knew / her husband had been removed, the kitchen renovated” (15). Camp bridges the space between art and life with her ekphrasis. What is actual begins to blend with what is constructed. We are constantly in flux, constantly renovating our lives, adding things, removing others, just as an artist might create her or his masterpiece. Aren’t our lives our ultimate masterpieces? What makes up our worlds is smashed together, glued, painted, constructed, fabricated. This is how we grapple with the world. Camp makes the grappling into not some means to an end, but into the thing itself. There are infinite ways to reimagine, and it is in that plural space, with renovations, art, and yes, crisp salmon, that we survive.

Think of the word survive, the idea that we continue to exist, in spite of the world, despite any predators that try to destroy us, despite our own predatory behaviors. Camp’s poems speak to the “seams of desire,” the places where things are put together, which are also the places where things can come apart (“Remember It Was” 11). She holds the reader in that liminal pause, that reading nest, where we are temporarily among the compilation of words, twigs, fabric, life, gin, ice, hunger, birds, glass. To be in this reading nest is a fascination. Camp gifts her readers with an experience that allows us to live in many of life’s layers simultaneously. Her poems put us in a place that is only inhabitable by the imagination, and yet we are there, held between life and the art that is created from life. We are consuming while being consumed, always taking and always took.

Took House is also a perfect book for fall, for thinking about an ending year which is nothing that we expected. As you open its cover, you will enter a space where only the best poetry can bring you, a space where everything is always on the verge of something else. Each poem gives us a breath of obsession, a moment to relish in the moment, a detail, a piece, a way to know something in a world where knowledge is ever fleeting. Camp’s last poem in the book, “Homeostasis: Autumn” delivers an ending that is both unexpected and hopeful: “A squash we didn’t plant has come in gold across the aspen roots,” and then “The whole day has nearly disappeared and night is a ruffle about to blossom” (70). Took House is compelling and astonishing. It will leave you wide-eyed and bewildered in the best possible way.