For those of us enamored of the Western European art tradition,The Getty’s current exhibition, Renaissance Nude, is a bonanza.

Although non-didactic, it is a thematic presentation utilizing specific works of art to elucidate its thesis that nudity appeared with frequency in works by both Italian and Northern European Renaissance artists. In that sense, it is a curatorial triumph. Included are masterpieces by some of the most significant 15th and 16th century artists of Italy and Northern Europe. Among them are: Antonio da Messina, Giovanni Bellini, Dieric Bouts, Piero di Cosimo, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Donatello, Jean Fouquet, Hans Memling, and Titian. Plus, there are drawings by Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.

Representations of the nude figure, male and female, have been evident in Western European art since the sixth century B.C. when Greek artists began to make increasingly naturalistic depictions of the human figure. The uncovered human body was presented for its intrinsic beauty without restraint. This concept embraced women as well as men, with females being portrayed as Venus and other goddesses. This practice did not prevail for centuries during the Middle Ages. In the 15th and 16th centuries, both the Italian and Northern European Renaissances shared a common objective – to reactivate the worlds of Ancient Rome and Greece and to initiate a new society encompassing that heritage.

Recently, “renaissance” has become a colloquial term used by writers, commentators and commercial enterprises. To avoid any possible confusion about the term “renaissance,” it is worth examining its roots. Furthermore, this will help clarify the underlying thesis of this exhibition. In his 1860 publication,The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, art historian Jacob Burckhardt described the core of the Italian Renaissance as the revival of antiquity – particularly Greece and Rome. While writers exhumed ancient texts, painters and sculptors used ancient statutes as inspiration. Some artists like Leonardo even engaged in the dissection of human bodies in order to study them. Thus, the representation of unfettered reality became a guiding principle while, at the same time, reflecting the achievements of Ancient Greece and Rome.

The 14th, 15th and 16th century European classical revival began in Italy and spread to France, Germany and The Netherlands. These paintings by Jan Gossaert (The Netherland) and Hans Memling (The Netherlands) and Antonello da Messina (Italy) demonstrate how the shared concept of reinvigorating antiquity could be interpreted so differently. Piero di Cosimo’s The Discovery of Honey by Bacchus (Not illustrated) is a joyous light hearted celebration, while Jean Fouquet’s Madonna and Child Surrounded by Angels, (Not illustrated) is a serious religious presentation and Lucas Cranach The Elder’s A Faun and His Family with a Slain Lion, (Not illustrated) presents a mythological theme.

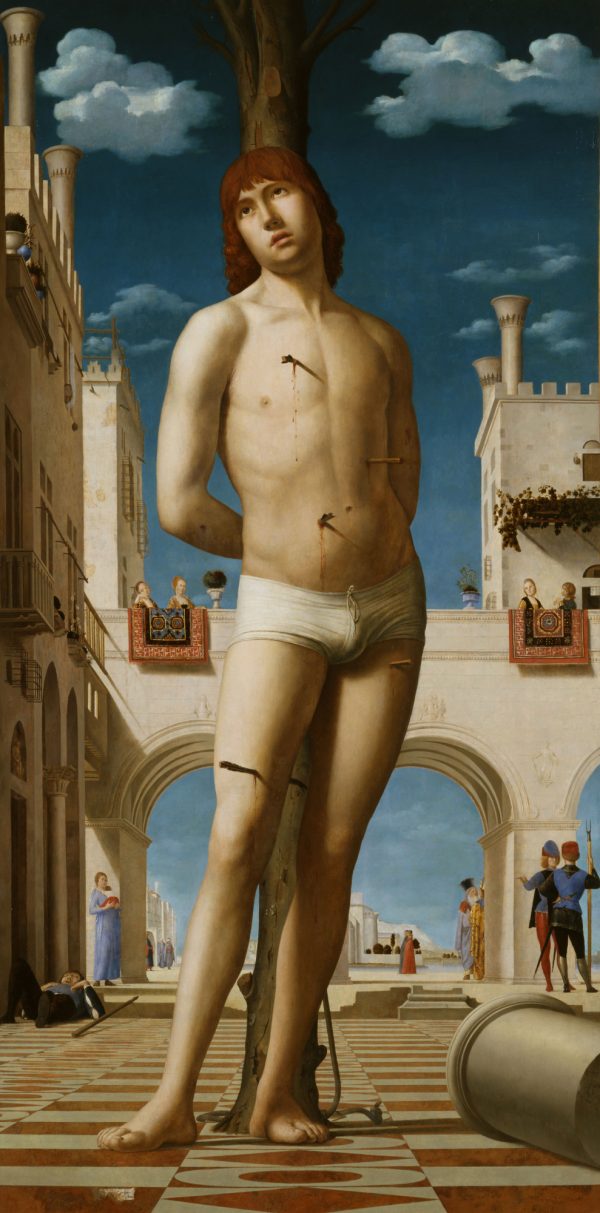

This painting by Antonello da Messina is outstanding both in terns of technique and subject matter. Until the mid- 15th century, Italian artists painted exclusively with tempura on wooden panel. Oil painting on canvas developed in Northern Europe and was adopted by Italian artists. Antonella da Messina was one of the first Italian artists to use oil paint on canvas.

Saint Sebastian, a popular subject for Renaissance artists, was an early Christian saint and martyr. According to traditional belief, he was killed during the Roman emperor Diocletian‘s persecution of Christians. He is commonly depicted in art and literature tied to a post or tree and shot with arrows. His image was invoked for protection from The Plague.

Although Florence was unquestionably the center of the Italian Renaissance, manifestations appeared in other centers such as Venice. The Venetians are represented here by paintings by Giovanni Bellini and Titian. However, nothing on display in this exhibition evokes the massive sensuality of Titian’s Urbino Venus.

This one painting has for five centuries stood as the unquestionable symbol of the Italian Renaissance nude. I consider it to be unfortunate that it was not included in the exhibition. It now hangs in The Uffizi in Florence. I recall having seen it and having been transfixed by its beauty and sensuality. There can be numerous valid reasons for its being unavailable: fragile condition as well as the costs of insurance and transportation.

However, with regard to this exhibition, as much I admire the selection of objects and associated scholarship, I missed the sensual punch of this painting, or perhaps of another with similar attributes.