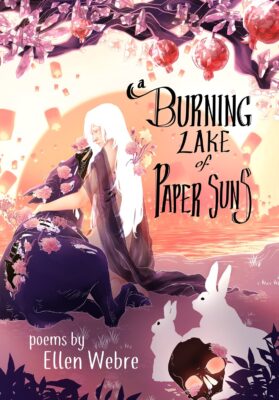

Poetry Review: A Burning Lake of Paper Suns by Ellen Webre

I move as deer, as jackrabbit in hawkflight, A red-breasted bird, a bonfire of oak and holly. I harness the sky with a cinnamon broom. I sweep away the blighted root, the sorrow choke. I make a speech of suppertime, bring milk and almonds enough to feed the beasts of every hollow. With ornaments for eyes, I horse dance on every threshold, demand a serving of red mandarins, a sip of buttered rum. Let me ring your home with bells and ribbons, let me partake in the blessings of this house, this communion, a shelter from the snow.

(“Metaphors for My Body in Midwinter”)

Traditionally, a young woman should be a “good girl,” embarrassed about her body and semi-comatose when it comes to sexual matters. Her stereotypical young male counterpart is a prince who, like the sun, wakes up the icy female with his kiss (see, for example, “First Love” by Stanley Kunitz). These expectations go by the wayside in A Burning Lake of Paper Suns by Ellen Webre. In this debut poetry collection, the speaker is no passive Sleeping Beauty; on the contrary, she has a warrior’s passionate heart.

Webre writes beautifully crafted poems about the speaker’s intense first love affair and its aftermath. I think there are perhaps enough “young-and-in-love” poems out there already, but I’ll make an exception because these poems aren’t like the usual ones. They don’t consist of embroidered cliches. Webre’s metaphors are creative, language extravagant, and word choice spectacular. These honest poems superbly capture the speaker’s volcanic awakening into full womanhood.

The speaker always calls this first lover a “boy,” not a “man” or even a “young man.” For example, she says he’s a “Molotov rebel, kerosene-guzzling war boy” (“Of Moss and Kerosene”). Presumably, he’s a young man age-wise, but she doesn’t feel he’s mature. Yet the speaker and he have an undeniably powerful mutual chemistry. She feels deeply connected to him, saying, “He is the salt and rice of me” (“The Budding Boy”). The speaker addresses her lover like this:

Out of my dreams, you arrive

like a burning lake

of paper suns...

............................................................................

...breathing in

the perfumed verses

of our sudden

but natural

intimacies.

(“Into My Arms”)

I like it that the speaker isn’t some uptight, repressed product of the patriarchy. She doesn’t just enjoy her lover’s touch. She “burns” for him (“My Closed-Circuit Songs, Frail Ground Without Exit”). These poems resonate with the speaker’s experience of sexual ecstasy:

I’ve scrimshawed my pelvis

with your name

and no one else

shall scream it again.

(“In the Bone Pit”)

In time, the speaker comes to experience her intense sexual cravings as a hunger that she wants to fill by devouring or swallowing her lover:

I fed on his gurgling throat, took my fill of his cadaver,

for I had been empty

of experience and I thirsted for

raw organs. He split his skull and no lover

could have been richer....

..........................................

...My flesh for his flesh my skin for his skin

one body knitted together so long as he stayed

in my stomach, so long as I could gnaw

and lick and chew and swallow.

(“Little Hunger”)

The speaker at times refers to herself as a “monstress,” which I interpret as the speaker’s experiencing such a compelling attraction to her lover that she feels out of control, at the mercy of “the slit of my undoing” (“Of Moss and Kerosene”). In “There Are Women Who Hold Skulls,” the speaker describes skull-holding women in mythic terms:

There are women who slide

fingers through eye sockets,

drink wine from skull caps,

swishing blood in round circles....

...........................................

...Hollow-eyed and paying no debts to sorrow.

Presumably, the speaker identifies with these “black-nailed” monstress-women. I am reminded of the Hindu goddess Kali with multiple arms and a necklace of skulls who is both goddess of death and protector of women and children. The monstress-woman metaphor hints at a darkness lurking in the relationship. The speaker remarks on what could be called a culture gap between her and the boy:

waking up again in the cheekbone curve of a boy who does not know the difference between a raven and a writing desk...

(“Almond Blossom”)

Eventually, perhaps inevitably, the love affair begins to decline, and the relationship deteriorates. The boy breaks up with the speaker. Now the speaker mentions “the sad girl in every monstress” (“An Alternate History of First Love”). However, consistent with the same brave young woman we previously got to know, the speaker wastes few words on self-pity. Although she’s tearful and distressed, she vows to forge ahead. And by the end of the collection, it seems she’s moved on to better horizons.

I think readers will find the poems in A Burning Lake of Paper Suns inspiring and rather fascinating. They teach us that experiencing your first love affair or relationship with a significant other involves coming to terms with your body’s urges, needs, and emotions. I applaud Ellen Webre for writing about this topic authentically and fearlessly. In the end, it all comes down to being able to love and accept yourself. Webre writes:

there is no witch

or wedding bed

or child born in a tulip

for you to foster

no daughter

no son

only the house of

belonging you

build yourself.

(“Brother Fool”)

*