I write this from my High Sierra campground where I am listening to Wolverton Creek flowing down below me. A Sunday afternoon breeze blows through my camp, and the songs of the birds make this place peaceful, contemplative, which is, I have come to understand over the last few days, the perfect space to read an anthology like Alongside We Travel: Contemporary Poets on Autism. Blocking out the noise of Los Angeles, where I live most of the time, has helped me to understand it.

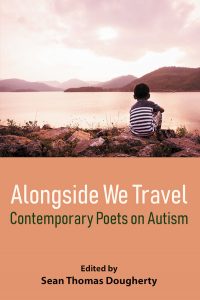

It is a book that needs time and space to absorb because beyond being a collection about autism, it is about empathy and basic humanity. These are subjects that need to be rolled around in my head to be understood. It is a book written by people who couldn’t be more passionate about the subject, these people who love others with autism or have lived with it themselves, and I haven’t read an anthology put together with more loving care than this one.

In the introduction, Sean Thomas Doughtery discusses a critic who wanted to make sure that certain kinds of poems about autism, poems in which poets complained about their lives, were not not included. However, Dougherty makes sure that everyone’s voice is heard

What this critic failed to understand, both as a parent and as an artist, was the ability to empathize and feel compassion outside of his own experience.

That is the job of poetry (xiii)

Helping to create empathy is of course the job of the poet, one of them at least, and this is accomplished well. It is why I, who generally read fairly quickly, have allowed myself to consume this slowly, to try to grow a little as a human in this world where so many other humans are so grossly misunderstood.

Helping to create empathy is of course the job of the poet, one of them at least, and this is accomplished well. It is why I, who generally read fairly quickly, have allowed myself to consume this slowly, to try to grow a little as a human in this world where so many other humans are so grossly misunderstood.

That misunderstanding of autistic people runs through this book. Many of the poets write about the distance that they feel or once felt because of their loved ones’ lack of language skills, and how empathy helps to close that distance. Jennifer Franklin captures the complexity of that relationship in “While Waiting, GodotInterrupts.”

…How can I

still believe in language — do words

have more weight than those bags we carry?

Have meaning? You could think me

an ignorant fool for believing (73).

These poets often describe an understanding that goes beyond words that involves love and patience.

This misunderstanding often leads to a bullying that the parents and friends feel as well. Rebecca Foust writes is “The Peripheral Becomes Crucial”

My son is gentler with moths

than people ever were with him,

and he chooses truth like breath (69).

Bullying, especially childhood bullying runs through the collection as it must in the lives of these young people. Just as powerful are the many depictions of adults who in their confusion do not know how to act around people with autism such as in Tony Gloegger’s “Good,” where a woman gives the child he is caring for

… an Oh you poor thing

pitying pose. I look past her, move

closer to Lee, touch his arm, instead

of smacking the nice lady across

her mouth (88).

Close contemplation and time and space is necessary for poems like these, necessary because it is important for me to inspect my own memory and past to see how well or badly I have treated other people on this planet whether out of some kind of childhood cruelty or adult superficiality. Much more important is to think about how I want to act in the future.

Along with these themes are fear and fatigue and burnout and the love so many of these people have for compassionate teachers and health-care workers.

This is a book that will stick with me. Tomorrow, I plan to walk up to the top of Tokapah Falls where I can get a view of the Kaweah River. I know that this collection will follow me up there to challenge assumptions and draw me into that silent space where understanding might come slowly and imperfectly and certainly not totally, but it comes.