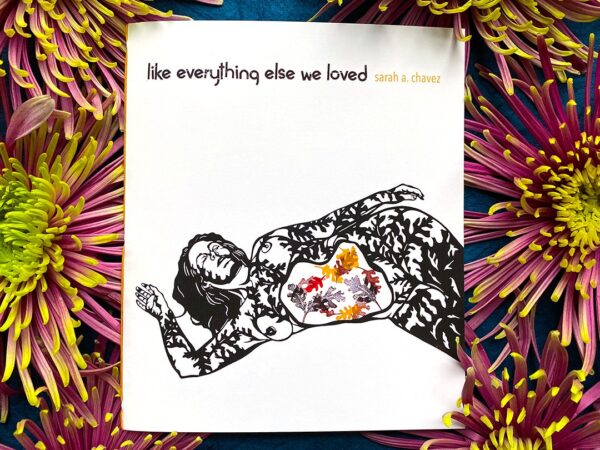

The poems in Sarah A Chavez’s new chapbook, like everything else we loved, have a sullen undertone, but they are not devoid of hope. In fact, the entire text offers a unique way to be hopeful when you’ve lost someone incredibly important—especially via that person’s untimely death.

The collection, which is epistolary in nature (rare in an entire collection of contemporary works), is forthcoming from Pork Belly Press.

In “Dear Carole, Dermatologists call the body a ‘trunk’,” the narrator says:

“Like losing you, the loss

of the tree was quick. One day,

diagnosis, the next day dust

from the wood chipper coated

the large hold in the grass

where the stump was pulled out.

A hole so big I could sit in it;

So I did, and I ran my hand

along the edges of still root,

connectionless beneath

the grassy surface. I put

my tongue to the limbs’ ashes,

sawdust caught in my lashes.

Even so, I like the idea

of being a tree” (5).

This poem tries to deal with the loss of something firm in the narrator’s life which has now disappeared. Because trees live so long, most of us forget that they all die—just like us. The narrator crawls into the emptiness where the tree used to be and we can feel that depth of loneliness we all feel one time or another.

The themes of death, loss of love, internal and surface level disease and mental health can help a range of readers cope with various types of loss but the poems do not play out like a lot of other love poems I have read. There is a darkness in Chavez’s work that is just so real and realistic. The text doesn’t sugarcoat anything, and it doesn’t try to be happy. The narrator is just trying to be.

In “Dear Carole, it hurts to look at things,” the narrator writes:

“I am the ink, you the ghost skin

the paper, and the moment

I stop writing

you’ll disappear again

taking these words with you” (7).

Like an offering to a lost love, the poems offer a chance to try and heal, but not in the cliché ways of polite society. Here, it seems like the narrator is working through the fear of losing someone completely. Death takes people away in one way, but then we slowly lose them more over time. When someone dies people say things like “time heals all wounds” or “they’ll still be with you” and other such nonsense, but loss of loved ones often seems to never dissipate. Chavez’s collection does not attempt to comfort the reader, because the narrator finds little comfort in Carole’s death. Carole is obviously one of the most important relationships the narrator has ever had, and I think we can all relate to the collection in this way, whether we have lost loves due to death or to just falling apart. Loss always seems to connote an emptiness and the work does a good job at unboxing the empty shell left behind by this sort of loss.

The narrator of the letters keeps the lover alive through the act of dreaming. In “Dear Carole, in my dream last night,” it says:

“I hear it like a stage whisper, breathing in my ear,

Nina Simone’s ‘I put a spell on you.’

I like this song, I say, shouting again

to cover the distance and din of your voice

reverberating against the mirrors. You don’t respond” (8).

The narrator walks the reader through the stages of grief, ending the collection with ghosts. In “Dear Carole, I look out the window,” we are left with a stark but somehow hopeful image:

“you will

feel the tingling

touch of my fingers

on your phantom limbs

and remember

you meant to haunt me”

And even though ghosts may not sound hopeful at first—when you’ve lost someone you can’t live without, you’ll understand that haunting is still presence and sometimes that has to be good enough because it’s all you’ve got (12). I loved every word of like everything else we loved because it helped me cope with my own hauntings. And it can help you, too.

***