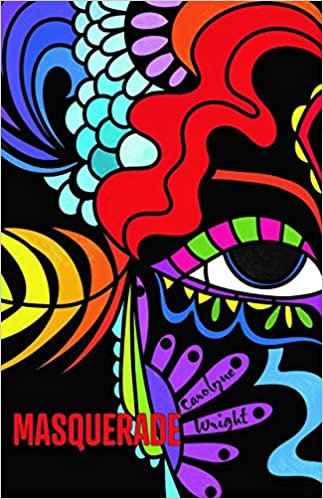

The new memoir in verse from Carolyne Wright arrives at a moment where readers seem particularly open to hybrid, genre-bending poetry books. Like both Rachel Mennies’ The Naomi Letters and Joy Ladin’s The Book of Anna, Wright’s Masquerade uses poems as a series of narrative windows into the history of a complex relationship. Wright’s book depicts the bourgeoning love between a white woman and a black man – both of them poets — who first meet as neighbors in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

Wright’s narrative jumps between several different locales: Provincetown, New Orleans, and Seattle, among other places. Further, Wright’s memoir relies entirely on verse to tell her story. This choice empowers the poet to demonstrate her mastery of both English prosody and a spell-binding, dizzying array of poetic forms – quatrains, endecasyllabic verse, the list poem, the triolet, the sestina and the ghazal, and more. Strikingly, the very artificiality of these forms – how the parameters (at times radically) compress language and rhythm – is precisely what helps Wright to forcefully articulate, both the progress and collapse of the love affair and the asymmetrical pressures that systemic racism places on the lovers. This combination makes for a series of increasingly explosive scenes that transcend narration and become drama, as when the black poet enters a French Quarter boutique where his white lover is shopping. The white female store-owner reacts to his arrival in no uncertain terms:

All the doors in Miss Lucille’s face

slam. Get up out that chair

miss, less you mean to buy it.

By the masquerade ball mannequins

Your face frozen into a Benin mask,

heartswood’s mahogany cheekbones scored

with the slashes for resistance,

fear. The only face that Miss Lucille

Ann would ever see. . .

Elsewhere, the elegance of the poetry highlights the messiness of this relationship, where male privilege and betrayal also reside, cheek by jowl with white privilege. The poet hides none of these paradoxes, all the while sharing that, even in memory desire abides:

the casual forward thrust of pelvis

under stiffened denim. Heft

And penetration, flutter-cries

of my breath and girl-come,

my lips that take you in.

In this way, Masquerade unfolds at once as remembrance and witnessing but also as celebration of sexuality and the subversive possibilities of joy.

Wright is an established poet with an impressive list of books, and she is well-known as an expert formalist – a poet at home with all manner of complex poetic modes. But in Masquerade, Wright does something new and unexpected with her talents. She uses that very formal mastery to offer her most deeply personal and revealing poems yet, with a brilliant result. The poems are shattering and audacious, moving, and at times even comic. Experiencing the collection as a narrative, readers are continually invited into intimate, private spaces, where we never feel like invaders, but rather witnesses, comrades, and compatriots, in the struggle that we are all in to understand and overcome the racist legacy that touches all of us here in the US. We emerge from the story of Masquerade, chastened but also reinvigorated, and even, inspired, to share our own stories, and to listen to the stories of others.

***