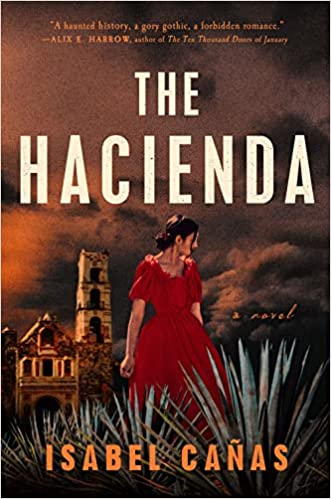

I love a good Gothic novel, its mystery, its lovelorn pining, a house that haunts either supernaturally or through memory. The Hacienda brings the form in full when Beatriz, a new wife to a wealthy landlord, travels to a home she had no choice but to join. When her father died, her family was left destitute, and her only hope was to marry up. As a mestizo woman with family who had one foot in the aristocracy, the other in Mexico, the daughter of a General, she is lucky to marry Rodolfo who owns a village, an agave farm with a steady income, and the eponymous hacienda itself.

The house has everything, echoes of older grandeur, decrepit carpets and walls, and the promise that it could be something new. It comes with a Mrs. Danversesque woman who lives on the property in the form of Doña Juana, Rodolfo’s taciturn sister. In true Gothic form, Rodolfo abandons Beatriz to Juana and the house within pages.

The house reveals itself to Beatriz within that first day.

The writing is rich and swift moving as Beatriz’s minor haunting ratchets up slowly into an insurmountable evil, family secrets are uncovered, and the history of the town opens up.

But Cañas leans into her Mexican roots in the story which is what makes it fresh for the genre. It is when a local priest, Padre Andrés comes on the scene and Beatriz enlists his help to deliver the house from its haunting that the story bangs a left. For it turns out Andrés entered the priesthood in the midst of the Spanish Inquisition. It was the perfect cover for the fact that he is brujo. It is when Andrés, having done the usual Latin prayer holy water routine pulls out the big guns of his true native language and his spells in the indigenous language of the area (Cañas doesn’t anchor it to a specific language, which is interesting), we know the game is afoot. Yes, we are in a classic Gothic novel, but this one has different rules, and its layers unfurl to shine a light on erasure, the casta system, colorism, the patriarchy, local politics, the Catholic church, and belief systems.

The family story is rife with the strictures of inheritance within a patriarchy, and the limited choices women of that period had. From Beatriz’s position making the best of being married to a man she doesn’t love, to the back story of not one, but two villains, Cañas exposes us to layers of systems designed to keep people down. All of this without preaching. The complex manner in which the lives of Rodolfo’s family and Andrés’ village family are intertwined, and the ways in which each of those families function, do that work for us. In the meantime, Cañas crafts terrifying scenes of horror, building tension and real terror in a way that kept even this veteran reader of horror on edge. There are some ghostly images in this book I will not soon forget.

There are some curious language choices in the book, which I suspect may be more the editors than the author. While there are definitely a few Spanish words used in the story, the book translates the word brujo to the English witch, and la Llorona, so recognizable in much literature and in American movies by her real name, is translated to The Weeper. La Llorona is as big a character in American households as the Bogeyman, reducing her to The Weeper is baffling and takes the power from the character and her cultural resonance. You might as well change a Chupacabra to “beastie,” or a vampire to a blood sucker. This translation raises a larger question of meaning and when translation becomes erasure.

Not only that, these translations change the reading experience. The editors of the book have reduced brujo to “witch.” Brujerìa is a very real practice known in this country and across others, which may be echoed by Anglocentric witchcraft, but has its own identity and meaning. Witch is just a different concept.

Berkley, a branch of Penguin is located in New York, so perhaps this is where that translation issue lies, and also likely the italicization of Spanish words, which is odd in the first place (I love Daniel José Older’s take on it: “Why We Don’t Italicize Spanish”.)

Italicization feels unnecessary and othering to a language that has become a rich part of multicultural American English. We absorbed baguette, ballet, dossier, and foyer, yet only .03% of Americans speak French as a first language. It makes no sense to keep italicizing Spanish words we use daily. People who speak Spanish as a first language make up 13% of our population, and apparently 55% have learned it as a second language.

I’d invite New York publishing to think harder about when translation helps a story become clearer, and when it muddies it. Translating any language woven into English in this country to cater to the white gaze becomes erasure and makes a reading experience less rich for all of us.

*