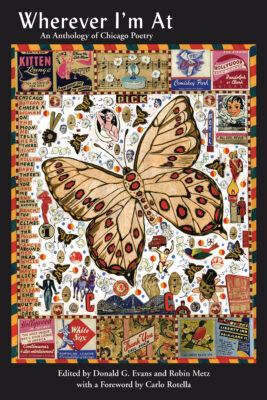

Review of Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry, Donald G. Evans and Robin Metz, eds.

Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry is the brainchild of Robin Metz, who gathered work for years before cancer finally led him to join forces with and ultimately pass the project on to the poet and writer Donald G. Evans. The work is filled with the kind of passion that one might expect from Chicago’s poets, who have complicated relationships with their great city. What moves me, however, beyond the fact that this is a collection of brilliant poets from Chicago is that it is also about Chicago, that is, every piece discusses the city itself. Like Sandburg’s famous poem, these try to capture and understand the city without necessarily defining it. Chicago is far too vast and complex to define, after all, but these poets help us to understand its transportation systems, foods, cultures, geography, and history. It is an exceptional collection that helps us to appreciate how the city and the nation has changed and is changing.

Food culture features prominently in this anthology as one might imagine. Typical of the collection is Li-Young Lee’s “The Cleaving,” where his narrator shops at a Chinese butcher and watches as the butcher completes the necessary tasks of preparing meat.

He lops the head off, chops

the neck of the duck

into six, slits

the body

open, groin

to breast, and drains

the scalding juices (127).

Lee always captures moments of the extraordinary, and he does so again and well here. These tasks are at once mundane and spectacular in their rawness. The moment of food becomes a kind of spiritual spectacle. In Sandra Cisneros’s “Good Hotdogs,” she describes the sacredness of a shared meal even when it is just hotdogs.

We’d eat

Fast till there was nothing left

But salt and poppy seeds even

The little burnt tips

Of french fries

We’d eat

You humming

And me swinging my legs (117).

Food is of course part of a universal shared cultural ritual, and the poets draw out that ritual here. What the editors have done is bring what is universal but also especially a part of Chicago’s culture.

The landscape of the city is also drawn as only residents understand it. Often, they see through the eyes of history and culture. Vincent Francone’s “Ashland Avenue” captures that sense of history.

Walking the same streets

my grandfather walked

in his paperboy cap, black coat

or seersucker, my grandfather and his

winsome ladyfriends wearing

pressed yellow dresses

and laughing in step

in spring along Grand

and Western, where his son

remembers playing baseball (212).

This is not only a place but a history individual to anyone who has lived there. These are often multigenerational memories that capture the emotional connection the residents have to it. Emily Thornton Calvo’s “My Chicago” captures her complicated emotional sense of the place.

Chicago is no woman

He is the cousin who owes you money,

pays you back with a wink and a smile.

You don’t ask where money comes from.

He is well-read, but better fed.

You can dress him up to dazzle in a tux,

but more T-shirt and jeans,

his shirttails run amok (232).

There is a genuine sense of pride with many of these poems for the scruffiness of the place and the toughness and courage of those who live in such roughness.

Although I am not from Chicago and have visited only once or twice, I found myself smiling and nodding and getting it. There is something about this Chicago that is purely of and for its residents, but my guess is that anyone who has lived in a big city as I have will understand the complication of these poems and the beauty in them as well. This is an exceptional anthology, and not just for the residents of this one town.

*