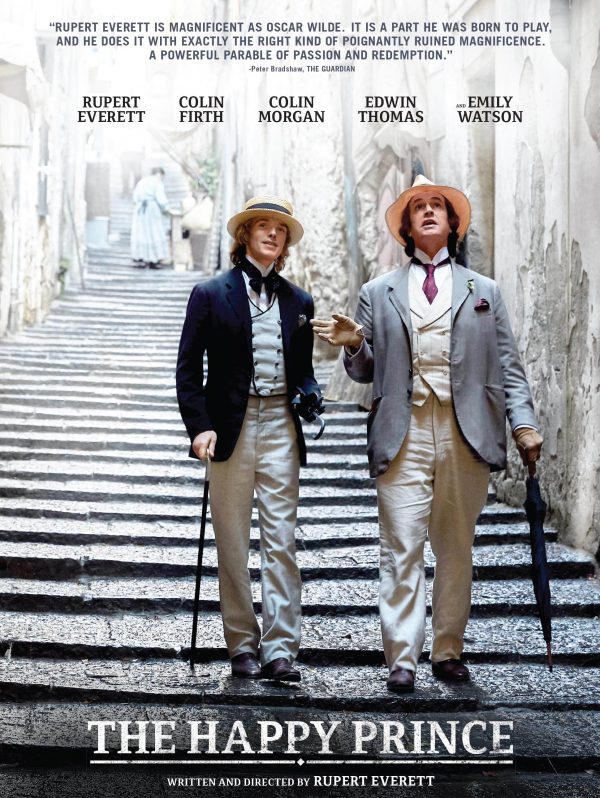

British actor Rupert Everett plays Irish writer Oscar Wilde in The Happy Prince, a movie he also wrote and directed. The title is taken from one of the fairy tales Wilde wrote for his children, Cyril born in 1885 and Vyvyan born in 1886, from his 1884 marriage to Constance Lloyd (Emily Watson). There are dream sequences of a younger-looking Everett telling this bedtime story to his two boys, but most of the movie is centered on the last three years of Wilde’s life, before his death in Paris on November 30, 1900 at the age of 46.

Oscar Wilde became famous in the 1890s, after writing his novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), and he was at the height of his success in 1895, when his play The Importance of Being Earnest was performed in London in February. After the Scottish nobleman, father of his 25-year-old lover (Lord Alfred Douglas, nicknamed Bosie), left him a note calling him a sodomite, Wilde sued him for criminal libel, but was himself arrested and tried twice for gross indecency. Between the two trials, his friends urged him to leave the country, but he decided to stay and was sentenced to two years of hard labor, from 1895 to 1897. When Wilde was released, a broken man, he left England for Dieppe in Normandy, France, then lived in Paris, where Bosie joined him and they moved to Naples, Italy.

Oscar Wilde became famous in the 1890s, after writing his novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), and he was at the height of his success in 1895, when his play The Importance of Being Earnest was performed in London in February. After the Scottish nobleman, father of his 25-year-old lover (Lord Alfred Douglas, nicknamed Bosie), left him a note calling him a sodomite, Wilde sued him for criminal libel, but was himself arrested and tried twice for gross indecency. Between the two trials, his friends urged him to leave the country, but he decided to stay and was sentenced to two years of hard labor, from 1895 to 1897. When Wilde was released, a broken man, he left England for Dieppe in Normandy, France, then lived in Paris, where Bosie joined him and they moved to Naples, Italy.

I meet Rupert Everett in Beverly Hills to talk about his film. This is the eighth time I interview him, in my long career as a film journalist; the first time was in 1991 for lunch at Butterfield’s on the Sunset Strip. See my article in Venice magazine.

The actor’s first encounter with Oscar Wilde happened in 1993, when he performed in Glasgow a play adaptation by Philip Prowse of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

“It was an amazing feeling, I had a natural ability with the text, the dialogue, the phraseology, the humor of Wilde; it was like riding a bicycle, for some reason I knew how to do it effortlessly and have fun with it. So when an actor finds a writer that he can portray very well, it’s quite a magical and lucky thing, the beginning of a treasured relationship.”

He then acted in two movies from Oscar Wilde’s plays, An Ideal Husband (1999) and The Importance of Being Earnest (2002), where the hypocrisies of British society are unmasked.

“Wilde definitely wrote about England, and people sometimes forget that he wasn’t English, because he’s writing in English about the English. In fact, it’s a very foreign point of view; what’s genius about it is that it’s such an outsider’s look at English eccentricities. So it’s very important to remember that he was not English. And that makes the tragedy of him being destroyed at the hand of the English even worse. The ideas of Oscar Wilde are actually very contemporary, he was writing about the façade of people and what went on underneath, this very complicated game-playing where you had to pretend to be somebody else in order to really be yourself. I love his witticisms, for example when he says, to love oneself is the beginning of a lifelong romance. That seems superficial, but around that same time Freud was talking about self-awareness and the subconscious, and Wilde was saying that you had to love yourself before you could love anyone else.”

Everett started writing the script in 2009, and in 2012 he convinced David Hare to stage a revival of his 1998 play The Judas Kiss, that covers some of the same events as his film. That’s when he knew that he was the right actor to play Oscar Wilde.

“The moving thing about Wilde is that he was an idiot and he did the wrong thing all the time. Someone accuses him of being a homosexual, which he was, and he was crazy to fight it, having lived such a brash life, always getting involved with scandals. So he brought everything on himself in a way. He had an opportunity of saving himself from going to prison at one point, in the afternoon he spent in the Cadogan Hotel, between the two court cases, before he was arrested. His friends were all telling him to go, leave England now, but he decided not to, he just stayed there until the police arrived. I think he must have had the example of Christ in his head there, he waited really to be crucified, because he realized that was the way he would become immortal.”

Rupert Everett was raised Catholic, as was Oscar Wilde. That would explain the comparison with the Christ figure, that Wilde talked about in his last letter from jail, De Profundis.

“Oscar Wilde paid such a price in the end basically for being a homosexual, that you can’t help but seeing him as a patron saint, or even a Christ figure, if you are a homosexual embarking in a show business career as I did. I take strength and inspiration from him for a way forward. Wilde very much had a Christ complex. This notion of Christ being half human half god is fascinating, and Wilde was like that as well, because he had god-like genius and traits, including an extraordinary compassion and a great capability for empathy, but on top of that he had these human qualities, which are pride, ego, greed, snobbery; and they undid him completely.”

Everett illustrates in the film how Wilde continued to indulge his passions, champagne, absinthe, cocaine, and sex with young men, even after he became impoverished and persecuted in exile. Also he could not resist getting back together with his beloved Bosie.

“What’s very touching about Wilde is what happens to him when he comes out of prison and he goes to live in Europe. He is the fallen star, the last great vagabond of the nineteenth century, punished and crushed by society, yet somehow surviving. He’s this broken person, he’s sick, but he’s still obsessed by this histrionic horrible hideous semi-literate upper-class boy. His wife had said, we can go back together if you never see this guy again, but he’s like a junkie and he can’t keep away. So they go to Naples together and then they have a fight and Bosie leaves. Wilde couldn’t write anything in the last two years; he was always pretending he was writing something, but he couldn’t. Everything that happens to him is so sad and tragic, his death was so painful and difficult; he got so disoriented and bewildered, and no-one deserves that, however vain and stupid and idiotic you’ve been.”

A title card at the end of The Happy Prince says: “Along with 75,000 other men convicted for homosexuality Oscar was pardoned in 2017.” This amnesty is called the Alan Turing Law, after the World War II codebreaker played by Benedict Cumberbatch in The Imitation Game (2014).

“Homosexuality really didn’t exist as a word and a category before Oscar Wilde. I think in a few hundred years’ time they’ll be looking at us saying how stupid we were; they were so obsessed by the difference between being black or white, being Catholic or Jewish, being gay or straight. We’re so into dividing humanity, we always think everyone else is the enemy, but in fact the enemy is ourselves. We are always trying to put you and me in one group and someone else in another group. That’s what people will think is infantile, once we’ve moved on. I don’t think we should criticize anyone else, really.”

Everett is unhappy about the turn toward divisiveness and intolerance that not only America has taken under Trump, but also Italy under right wing leader Matteo Salvini.

“It’s a very depressing time, really, there’s never been a more depressing time. Possibly this must be how people felt between the two world wars. It feels like that, it feels terrible. You always read stories about before 1914 or before 1938, and you wonder how people did not realize what was going to happen. And now people do realize what is going to happen, but you feel, what on earth can you do; so you are sitting watching it from the sidelines, as though it’s not about you. It’s very weird. But my country is a disaster, Italy is a disaster, Salvini is a horrible man.”

I would like to conclude with some words of empathy for the suffering of our fellow humans, so I suggest you read Oscar Wilde’s fairytale The Happy Prince, about a statue that asks a swallow to remove his sapphire eyes and bring them to the poor. I read this story to my child years ago, and I read it again after seeing the film. Rupert Everett’s mother Sara read it to him at night in bed when he was 6-years-old, and he never forgot it.

I would like to conclude with some words of empathy for the suffering of our fellow humans, so I suggest you read Oscar Wilde’s fairytale The Happy Prince, about a statue that asks a swallow to remove his sapphire eyes and bring them to the poor. I read this story to my child years ago, and I read it again after seeing the film. Rupert Everett’s mother Sara read it to him at night in bed when he was 6-years-old, and he never forgot it.