When Sebastian Junger (The Perfect Storm, A Death in Belmont, War) and I last spoke, he had just come back from Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, where he and photojournalist Tim Hetherington had shot footage that would become the documentary Restrepo. Restrepo, which my former company, National Geographic Films, released in 2010, was nominated for an Academy Award for best documentary feature. Tim Hetherington was killed in April, 2011, while covering the Libyan civil war.

Sebastian’s currently in New York, and we recently reconnected.

Adam Leipzig: We’re all so aware of how reactive the world is. I’m thinking about the riots in the Middle East over the past weeks, and also Salman Rushdie’s new book, Joseph Anton, which tells the story of his life under the fatwa. Have you ever had a personal encounter with violent reaction to your international work?

Sebastian Junger: When I was in Liberia, an English journalist wrote an article about how the country’s president, Charles Taylor was a cannibal. It was a pretty inflammatory thing to write, even about someone like Charles Taylor, who was horrible. He filed it as dateline Monrovia but waited until he was safely out of the country before he reported it. I was the only Western reporter left in the country. All of their rage went to me.

I was accused of having written it myself. They didn’t make the distinction between my name and his name. I was in an army garrison deep in the bush with army soldiers – child soldiers – high on crack or whatever they were smoking, and they heard that I was the guy who called their president a cannibal. It got extremely ugly and terrifying.

AL: Do you think there should be any limits on what’s printed or distributed? While The Innocence of Muslims video would be illegal in some countries because of their hate-speech laws, of course is not illegal in America due to our grand tradition of free speech.

SJ: It seems there could be room for some kind of law that permits free speech and also makes people legally accountable for incitement to violence.

I’m not a lawyer, and I don’t know how you’d phrase it or if it would be legally possible. But our society has negotiated that boundary between personal liberty and collective good for two hundred-plus years. Clearly, with the Internet, more thought has to be put into where that boundary is and how to protect free speech.

This is an example of where the lawyers and judges need to go back to work. We have to figure out how we take this to the next step in a way that takes into account the new realities of the Internet. Our foreign interests and national security are being undermined. People are dying.

AL: You’re now involved in medical training for journalists in conflict areas.

SJ: Tim’s wounds did not have to be mortal. He had a very dangerous wound – an arterial wound in his groin – but he died from loss of blood, and loss of blood can be slowed. He died minutes from a hospital where they might have been able to save his life.

If someone around him had the training and the equipment to slow the loss of blood, Tim might have made it to the hospital alive and might have lived.

When I found that out, I realized that I didn’t know anything about battlefield medicine – and no journalist that I know has that training either. When reporters are on salary with networks, their insurers mandate an expensive, high-end hazardous environment training course, where you relearn things all the things combat reporters already know, like what an incoming mortar sounds like. But none of that benefits freelancers.

Probably eighty percent of the reporters and photographers in war zones are freelancers – young freelancers who just go over there, on a wing and a prayer. They’re providing most of the news reporting. They have no insurance, no support, no training, no nothing.

I decided to start a medical training program for freelancers in war zones, Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues (RISC). Not for people who want to be freelancers, but people who know what they’re doing, who are already in that world.

Our first session trained 24 people, we have another training coming up in October, and we have a backlog of 100 people. We’re hoping to do three sessions a year and bring it overseas, too. We’re fundraising right now.

AL: What are you focusing on now?

SJ: I’m not covering any more wars. After Tim died, I did not want to be where there’s more combat.

I’m done with war, the nation is just about done with war, the vets are coming home. Now there’s the whole process of re-incorporating into society. That’s true for me as journalist as well.

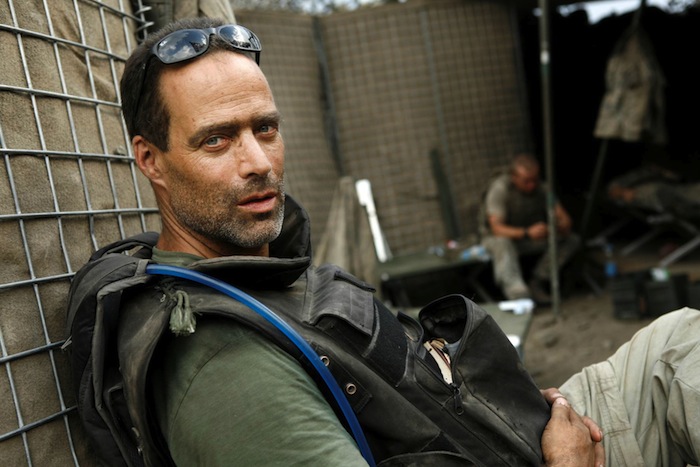

Photo of Sebastian Junger by Tim Hetherington.