Visiting an art exhibition can be an uplifting experience, but the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco takes the idea to a new level with its latest show, Awaken: A Tibetan Buddhist Journey Toward Enlightenment.

The exhibition is structured as a journey from the chaos of contemporary life through several stages of growing awareness, illustrated by almost 100 Buddhist paintings, sculptures, and other objects. In theory, at least, it leads the viewer to a heightened state of awareness, if not nirvana. For a non-Buddhist Westerner like me, it’s a thought-provoking tour of religious artworks that range from beautiful to perplexing to terrifying.

The show opens with a clip of Godfrey Reggio’s spooky 1983 film Koyaanisquatsi, with speeded-up shots of cars zooming along downtown Los Angeles freeways, past lit-up high-rises at dusk. Accompanied by Philip Glass’s hypnotic soundtrack, the film conveys the back-and forth frenzy of modern life, with everyone in a hurry to go somewhere for no obvious reason. It’s the essence of non-awakeness.

Paired with the film is the first example of Tibetan art — and one of only three contemporary works in the show — Luxation 1 (top image) by Tsherin Sherpa, who emigrated to the United States as a youth. The group of 16 brightly colored square panels seem to present details of some larger subject in a mash-up of Pop art and traditional Tibetan painting. There are close-ups of demonic faces, smiling skulls, bulging eyeballs, claws, multicolored sheep and birds, and a spotted green snake contemplating a big blue phallus. (The title means dislocation or displacement, the same theme as the adjacent film clip.) From here the exhibition begins its journey toward spiritual awakening.

Among the most accessible works in the show are a number of sculptures of the Buddha or his followers, typically seated and meditating. Crafted in copper, bronze, wood, or stone, they’re elegantly posed and often lavishly decorated with inlaid jewels or gilt or paint. The 18th-century Padmasambhava from central Tibet is a spectacular example, depicting an eighth-century Indian mystic who is said to have introduced Buddhism to Tibet. With his realistically colored eyes and mouth he presents a fearsome image of someone to be obeyed.

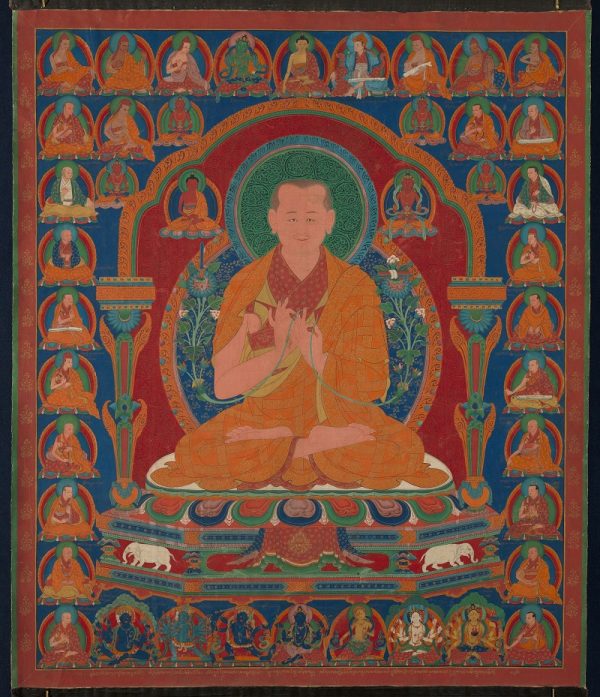

The paintings are more difficult to understand. They often feature a central image of the Buddha or a famous guru surrounded by dozens of secondary figures. Some have faded from hundreds of years of exposure to light.

Gorampa Sonam Senge (1429-1489), Sixth Abbot of the Ngor Monastery, from central Tibet in about 1600, is just such a painting. It shows the monastic leader as a smiling figure flanked by lotus plants on each side, topped by a book and a sword. The smaller portraits on the left and right represent his teachers and their teachers, while the demonic-looking figures at the bottom are deities closely associated with the abbot. There are also some exotic creatures at the bottom — a pair of white elephants, several fierce-looking, multi-armed blue deities — creating the overall impression that there is too much information here.

The work was intended to be an aid to meditation, reminding the viewer of the Abbot’s teachings and lineage. Yet the portraits are static and mostly monochromatic. The painting, like others in the show, has little of the visual energy of the sculptures or Sherpa’s three contemporary works. And without the excellent wall labels that explain the meanings of the artworks, most viewers would be baffled by the paintings.

The sculptures are another story, though. The meditating Buddhas and gurus display a calm assurance, while those depicting the monster-like terrors of the path toward awakening are astonishing.

Vajrabhairava, made in China as early as 1400, is a roughly four-by-four-foot polychromed wooden sculpture depicting a wrathful form of the deity who personifies the victory of spiritual wisdom over death. With a buffalo head that would be appropriate for a dragon, plus 34 hands on a stout humanlike body, he holds bells, knives, gongs, and strings of human heads.

As a work of art, it’s one of several demon-like sculptures that almost steal the show. It’s totally over the top.

Yet there’s another group of sculptures near the end of the exhibition — sexy couples in passionate embrace — that also represents the end of the journey toward enlightenment. Guhyasamaja and Sparshavajra, in gilt bronze from 15th-century Ming dynasty China, shows such tenderness and focus in the moment that it almost breaks your heart.

Awaken: A Tibetan Buddhist Journey Toward Enlightenment runs through May 3 at the Asian Art Museum, 200 Larkin Street, San Francisco. The exhibition was organized with the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, where it was on view last year. An extensive catalog by curators from both museums is published by Yale University Press.

(Top image: Tsherin Sherpa, Luxation 1, 2016, set of 16 panels, acrylic on cotton canvas; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund. Photograph © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, photo by Travis Fullerton.)