In the summer of 2013, I spent a week in the Tucson-sector of the US-Mexico border with No More Deaths, “a humanitarian organization based in Southern Arizona” that works to end the death and suffering of migrants crossing in the desert, when I had driven a carload of donations to their desert office in Arivaca, Arizona. I volunteered once before in the summer of 2011. The grueling experience included daily patrols and water drops—strategic, high trafficked points throughout the desert where volunteers delivered supplies of fresh water gallons, canned food, and socks in hopes of saving a person’s life. These drops meant carrying several gallons on your back while hiking in over 100 degree temperatures through rocky desert land that took you into canyons and up to the top of mountain ridges in a low-grade warzone scarring Tohono O’odham ancestral land, all while being acutely aware of the terrors faced by those you were trying to help.

After that first experience, I decided gathering donations and driving them from Los Angeles to Arivaca would be enough of an action. But as a two-night stay turned into five, and then six, I figured I might as well do a couple of water drops.

Elizabeth, a friend I’d met in 2011, a long-time volunteer who now lived in town, knew I was nervous to patrol and promised to take it easy on me. Taryn, a young, white punk-type visiting from Tucson for the day, was also coming along. It would be Taryn’s first patrol, and Elizabeth planned for the three of us to do a couple of car drops, long drives in a clunky donated truck over dirt roads to a GPS coordinate where we’d walk no more than a couple of hundred feet with our supplies. The hardest part would be the carsickness that came from bouncing incessantly over pocked and washed out dirt roads.

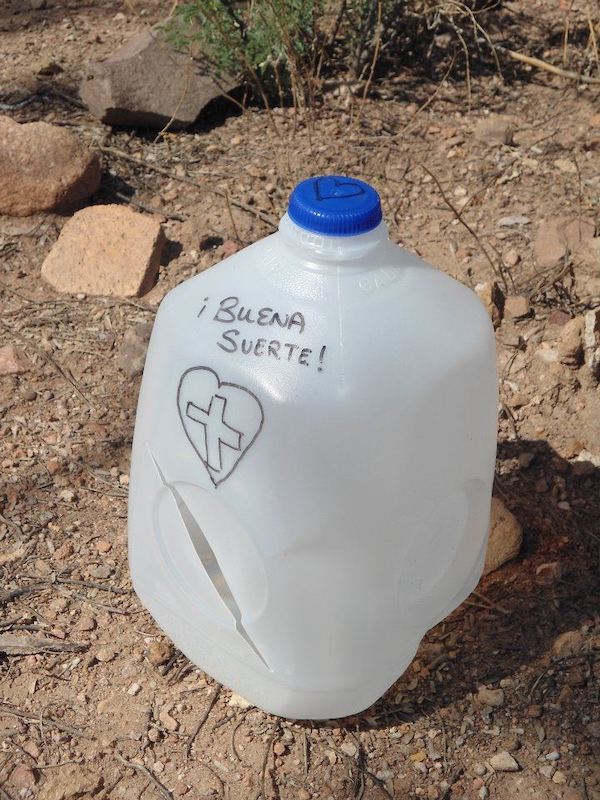

At our first drop, we all took out Sharpies to write messages on the water gallons. Short messages of hope, welcome, or peace were left on bottles as signifiers to migrants that the water was safe and meant for their care. Right away, Taryn wrote a big, fat “FTP” on the side of a bottle. Elizabeth groaned.

What was wrong? Elizabeth said messages like “FTP” could provoke violent reactions from Border Patrol who were already known to destroy water gallons left for migrants. NMD had been recording such vandalism with videos evidence. The worst showed a Border Patrol agent smashing all the gallons against rocks and then pouring what was left into his hat to feed to his horse as he cackled maniacally.

If Border Patrol Agents saw “FTP” on a water gallon, they might destroy the entire supply in revenge, and if they had people in their custody they might do worse. Without meaningful regulations or mechanisms for accountability, it was hard to know what they might do, but our job as humanitarian aid volunteers was to minimize suffering and serve those most vulnerable in the desert. So even though the anger was justified, taunting BP didn’t serve the migrants.

My time with No More Deaths taught me about how to be an organizer and an activist, and now as I watch the news on the #BlackLivesMatter uprisings, I think back to the desert and the word “service.” I want to be of service to the movement and remember my words and actions have the potential to affect others, both positively and negatively. I want to serve the movement responsibly by listening to the organizers who have been doing this work long before me. And it’s my hope that any person who cares to be an ally will do so too.

Thich Nhat Hanh says, “Sometimes you think you are doing something for someone else’s happiness, when actually your action is making them suffer. The willingness to make someone happy isn’t enough. You have your own idea of happiness. But to make someone else happy, you have to understand that person’s needs, suffering, and desires, and to not to assume you know what will make them happy.”

Whatever way you find to join the movement—because there are various ways to serve—before taking action, ask yourself, is this something I want, or is this what the movement wants? How might my actions help or hurt those I mean to serve? If you’re unsure of those answers, listen to Black leaders, follow your local Black organizers, pay attention to their language—BLM-LA is demanding Mayor Garcetti “Defund the Police”—and then watch for ways help. Do not misunderstand my words. I’m not telling you to bother the Black people in your life with these questions. They are too tired and hurting. What I’m saying is before you go out to a march, or call an elected official, or post on social media, be sure to do your homework.

“10 Steps to Non-Optical Allyship” by Mireille Cassandra Harper, an online resource published on Instagram and Twitter, is one place to start. And once you’ve read Harper’s piece, keep researching because to join the movement responsibly will take work from all of us, but our Black brothers and sisters deserve our work.

As James Baldwin wrote in If Beale Street Could Talk, “[Being in trouble] you see people like you never saw them before. They shine as bright as a razor. Maybe it’s because you see people differently than you saw them before your trouble started. Maybe you wonder about them more, but in a different way, and this makes them very strange to you. Maybe you get scared and numb, because you don’t know if you can depend on people for anything, anymore.” Black people are fighting for their lives. Don’t be their next razor.

Listen. Learn. Serve.