I have mixed personal feelings about the comics of Art Spiegelman. I respect and revere his status in the field, yet feel strangely distant from the actual work. I think his recent book, Breakdowns, a reprint of his ‘70s and early ‘80s experimental work more than doubled with new material, is as great as his 9/11 volume, The Shadow of No Towers, is negligible. Of course, everything he has drawn, or probably ever will, is overshadowed by the 600-pound gorilla known as Maus. Spiegelman’s tale of his father Vladek’s experience in Auschwitz, intercut with Spiegelman’s present-day frustrations with him, was a breakthrough book in the eighties, and to this day is one of the few graphic novels the public is generally familiar with. It’s usually Exhibit A in making the case that comics can contain more than juvenilia.

I hedge a bit when it comes to Maus. Maus is genuine and powerful. It is authentically a great work of art and has packed into it an astonishing amount of sheer craft. Historically, artistically, and in recognition of its unique contribution to Holocaust literature, there is no arguing that it’s an undisputed classic of the comics medium. And yet…

I’ve read it cover to cover only once.

As deeply as I respect the achievement of Maus, it has never touched me in a significant way (and this is speaking as a fellow Jew). I didn’t think about it much once I’d read it until I scooped up the CD-ROM on the making of the book (now available in the excellent book-on-the-book MetaMaus) and discovered the painstaking depth of Spiegelman’s creative process. Still, the distancing technique of substituting animal heads for various nationalities renders the story inert for me and slightly cold. I am very willing to believe this is my own problem, and not that of the justly-honored Pulitzer-Prize-winning Maus.

Ultimately though, none of that matters, because from where I sit, the crowning achievement of Spiegelman’s career can be spoken in one three-letter word:

RAW

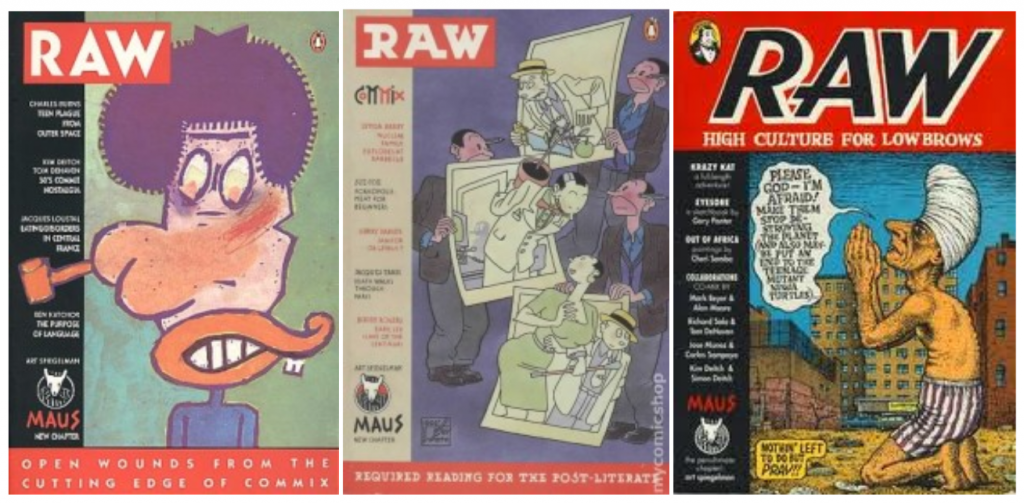

The title alone is a sharp punch to the gut, begging to be printed in 75-point font with the brightest shade of red known to Microsoft, surrounded by thick, raggedy borders. It at least deserves to be displayed in its original house style:

RAW is the watershed anthology edited and heavily contributed to by Spiegelman and his wife Francoise Mouly published into a dire ‘80s comics market. Freely mixing American and European artists (and one each from Japan and Zaire), nothing like it had ever been attempted. This allowed them to choose the best comics the world had to offer at that time, and the quality of the work is uncompromising.

Though I was already knee-deep in comics reading at the time of its publication, RAW essentially predates me. It was too sophisticated and too obscure for the teenage me when it was being released. I vividly recall the moment when I spotted on the stands a copy of Read Yourself RAW, the one and only collected volume that contains only the first three issues of the original eight. Ever the arbiter of good taste, I furrowed my brow, thumbed through it for a minute or so, shrugged my shoulders and put it back. It was far too peculiar and expensive ($15.00!) to feed my ongoing habit of reading the serialized adventures of costumed muscular men and women beating each other up. I have since rectified my mistake and tracked down the reprint collection in its unique, rare brilliance.

RAW was published in two parts, the big one – eight self-published, independently distributed tabloid-sized issues – and the small one – three Maus-sized, book-length issues published by Penguin Press. Both are essential. The Penguin books are better. The three issues of RAW volume two are nothing short of the perfection of the comics anthology.

This is not to slight the earlier, bigger RAW in the least. The original issues were released into a market that contained virtually no other material for adults, save the more visceral, zany anthology series Weirdo. Even that, put together by Robert Crumb recovering from his ‘70s slump, was more a look back to the underground comix movement than one that broke ground ahead of itself. RAW provided a forum for the earliest notable work of some of the greatest comics creators still writing and drawing to this day – Chris Ware (a grand Spiegelman discovery if there ever was one), Charles Burns, Kim Dietch, Ben Katchor, Gary Panter, Lynda Barry, Kaz, Julie Doucet, Bill Griffith and one Alan Moore. Most of these were in the first flush of their creative growth. In other words, they were still, well, raw. It must have thrown quite a challenge at their feet being printed alongside the far more seasoned overseas talent.

RAW volume one is partly known for the playful gimmickry that accompanied their high-art aspirations. Issues were released with enclosed mini-comics, trading cards (with stick of gum) and a flexi-disc compilation of sound clips from Ronald Reagan speeches. Another issue had a piece of the cover hand-torn by the RAW crew personally, and readers found the ripped piece taped inside the issue. Installments had jokey titles such as “The graphix magazine that overestimates the taste of the American public” and “The graphix magazine of postponed suicides.” Its large size showed off the art in the best possible way, but in doing so, at only 26 pages per issue, necessarily emphasized art and design over story. Big RAW was like a ball peen hammer to little RAW’s fine crafting tool.

My “smaller RAW is better” pronouncement comes with one monolith-sized caveat: I have never seen most of bigger RAW issues. These 30-year-old magazines were low print run, and because the right to publish the contributions as a unit no longer exists, they can never be reprinted. Copies often sell for hundreds of dollars apiece (I think seven and eight can still be found for under fifty). Thank the gods for the more accessible Read Yourself RAW collecting 1-3, because it’s the only example of big RAW one can read without plunking down a sizeable chunk of change. Meanwhile, you may freely regard my critical comparison as uninformed.

With that in mind, do yourself a favor and lay out ten bucks a pop on the three issues of RAW volume two. Each one is a powerhouse. At about 200 pages each, you can open to nearly any random page and receive an entirely unique, deeply personal take on how an artist can express in comics form (including the in-progress segments of the aforementioned Maus, perhaps better digested in smaller chunks). The increased length gives pieces the freedom to continue as long as they need to, the longest being Kim Deitch’s forty-one page classic, “Boulevard of Broken Dreams,” since available in expanded form as its own superb graphic novel.

Plus, RAW still plays with format, printing certain segments on different colored paper or newsprint. “The Child Slave Rebellion” in issue two has, not one, but two foldout pages. In an inspired move, Spiegelman and Mouly included public domain comics from deceased, nearly forgotten masters – a bizarre hick comic by Boody Rogers, six pages from the mad mind of Basil Wolverton, and George Herriman’s only continuing Krazy Kat narrative, among others. Several politically left prose articles on fairly random topics are thrown into the mix with illustrations, and are the least successful element of the package.

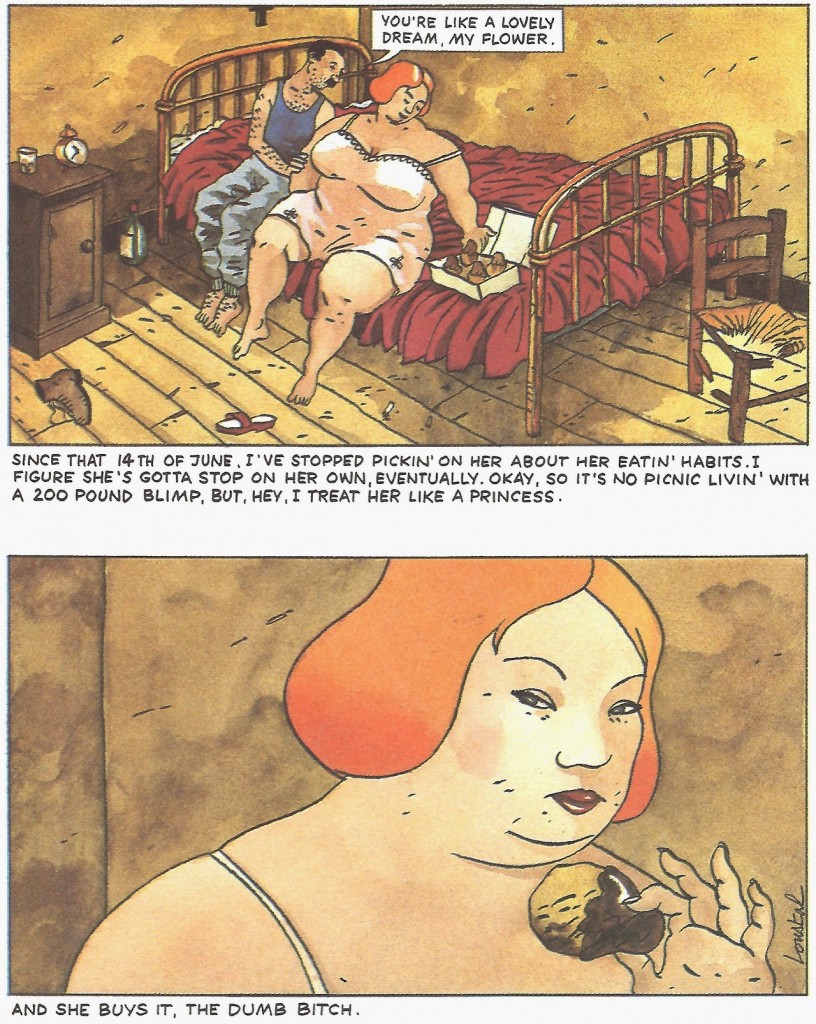

The new comics stories are too numerous to review, obviously. All they have in common is they are completely original, running the gamut through hilarious, surreal, somber, wildly experimental and deeply affecting. Jacques Loustal and Villard in their eight-page, sixteen-panel “Bulimic” deliver one of the most heart-wrenching stories I’ve seen in any medium about a married couple who lose their children in a fire. It’s narrated from the point of view of the heartless husband who’s only concerned with his wife’s weight problem and the safety of his precious sedan.

Pascal Doury’s “Paul” imagines the inexpressible anxieties of a small boy in one length-wise image per page depicting the child’s point of view. Paul clearly has no idea how to process the world around him, which he experiences as a riot of clashing bodies, deadly flying objects and exposed penises (even on females and teddy bears).

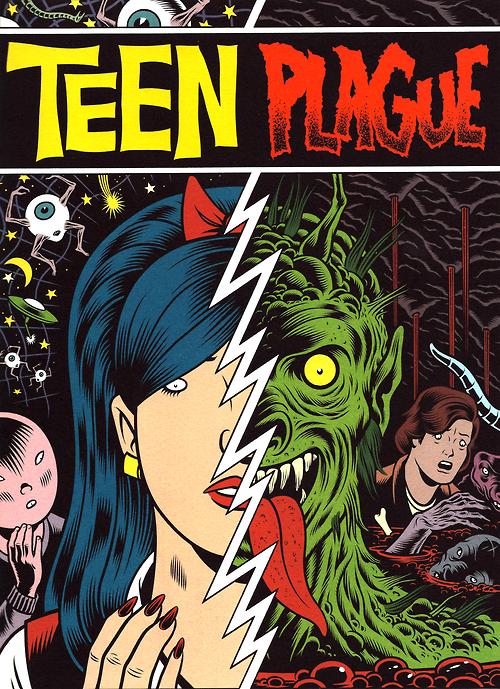

In “Teen Plague,” Charles Burns offers a chilling prototype of the story he later expanded to become his Black Hole graphic novel.

One of my favorites is Richard McGuire’s “Here,” showing different perspectives from the inside of a single house through the ages, including the pre-structure grassy field in the 1700s, into the future of 2030 and back to the dawn of time. McGuire skips around the centuries wildly with inset panels and juxtaposed actions creating a fascinating collage of human existence.

I’m just scratching the surface here. The three issues of RAW volume two combine more than fifty comics artists’ work from ten different countries, and there isn’t a single one who phones in their effort. The result is a compact pile of comics the likes of which we’re not ever likely to see again. Just about any other anthology is inevitably going to be a mix of hits and misses, but Spiegelman and Mouly were right there at the cutting edge back when, in America at least, there were few other places where short pieces like these could see print. Integrating those fledgling creators with the best of archival and foreign material was a master stroke, making a collection that stands alone. There is no better source I could use to show a comics beginner the wide open range and endless variety that the art form is capable of.

With Maus as a perennial presence in the field, RAW has faded back into history. It’s time the work got its due as its equal.