A gigantic dragon greets visitors to a new exhibition of contemporary Chinese art at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The dragon, 85 feet long and twisting above the ground-floor atrium of the museum, features a head made of junked bicycle parts and a long tail of twisted rubber inner tubes. It reminds you of a Chinese New Year parade float in some alternative mechanical universe, and it’s a knockout.

Up on the seventh floor of the museum, where “Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World” is installed, the show itself is more of a mixed bag. With more than 100 works by about 60 artists, it ranges from painting and sculpture to film, video, and photography, as well as performance and found objects. It’s both instructive and at times baffling.

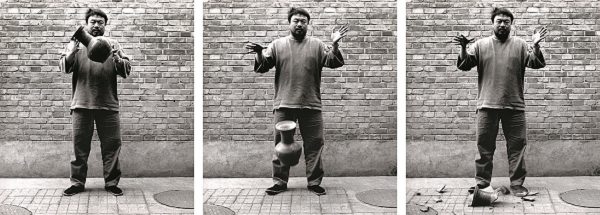

There are some well-known works, like Ai Weiwei’s “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” of 1995. The series of three photographs depicts the artist holding a vase in his hands, in midair as it falls, and smashed on the floor. It’s a deliberately provocative work about the destruction of the old culture, among other things, and it sticks in your mind.

Much of the exhibition falls into the category of conceptual art, or harks back to Dada and Surrealism, and some of these works are as clever as Ai and the Urn, if not as well known.

In Lin Tianmiao’s “Sewing” of 1997, for example, an old-fashioned sewing machine powered with a foot pedal is wrapped all over with cotton thread, almost like a tight-fitting garment. The sewing surface functions as the screen for a foot-wide circular video projection of a pair of hands that seem to guide cloth through the sewing machine. It’s an elegant juxtaposition of antique and modern, and a not-so-subtle commentary on the repetitiveness of factory work.

The exhibition covers the period of 1989, when the Tiananmen Square protests were crushed, to 2008, when the Beijing Olympics seemed to show that China had fully entered the modern industrial and consumer world. Many of the works comment on that transformation, some directly, some more obliquely.

A painting by Wang Xingwei, “New Beijing” of 2001, seems to copy a famous news photograph of a group of men on bicycles carrying away the victims of Tiananmen Square. In the painting, however, the victims are a pair of large penguins. The image is certainly surreal, though the meaning is far from clear.

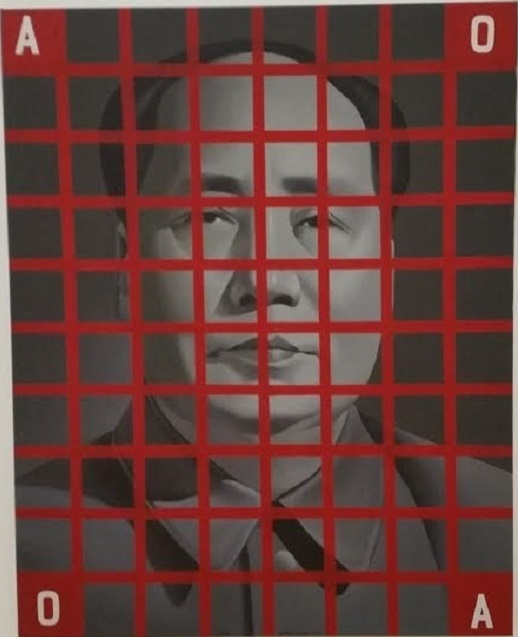

Another striking yet ambiguous painting, Wang Guangyi’s “Mao Zedong: Red Grid No. 2” of 1988, presents a monochromatic head-and-shoulders portrait of the nation’s founding father overlaid by a grid of thick red lines. Has the Great Helmsman gone to jail? Does the grid simply represent preparation for transferring the image to a much larger, billboard-sized version in a public square? Is it just a surrealist joke?

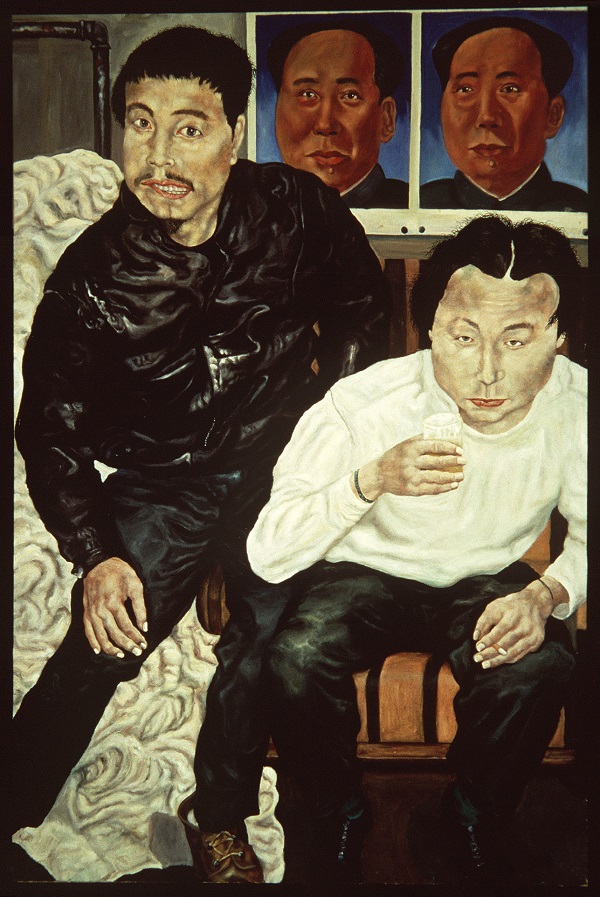

Some of the paintings take a more straightforward approach, such as Liu Wei’s expressionistic “Two Drunk Painters” of 1990. Sitting before a double portrait of Chairman Mao in the background (him again!), the two young men in blue jeans stare straight out at the viewer. The one on the right in a white sweater holds up a glass as if making a toast. The one on the left in a black leather jacket seems to grimace in confusion. What it all means may be beside the point. The painting presents two distinct and memorable characters, like Van Gogh’s portraits of his friends at the Arles cafe.

There’s a lot more realism to be found in the show’s documentary photographs, videos and films. Zheng Liu’s straightforward black-and-white portraits of ordinary working people are among the standouts. There are convicts and coal miners, a Peking Opera actor playing a woman, and a trio of young strippers barely clad in matching floral fabric.

The more frustrating works in the exhibition are the conceptual installations such as Xu Tan’s brightly colored cheap toys arranged in “Made in China” of 1997-1998. It’s obviously a commentary on how the nation’s economic rise has been largely powered by making vast quantities of cheap, ephemeral junk. As a work of art, though, the more you look at it, the less clever it seems to be.

“Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World” runs through February 24 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 151 Third Street, San Francisco. It previously was mounted at the Guggenheim museums in New York and Bilbao, Spain. An extensive catalog is published by Guggenheim Museum Publications.

Top photo: Chen Zhen, Precipitous Parturition, 1999, rubber bicycle inner tubes and sheeting, bicycles, steel, aluminum and plastic cars, and acrylic paint, courtesy of K11 Kollection; photograph of installation at SFMOMA atrium by Stephen West