Neutrality and appeasement are the tenets that most people associate with Sweden and its citizens during the Second World War. The Last Sentence, a biopic from preeminent Swedish director Jan Troell, shines the spotlight on one of Sweden’s iconoclastic heroes of that time, Torgny Segerstedt, a journalist and editor who used the power of the pen and press to alert his countrymen of the dangers of Hitler and Nazism. While Segerstedt is a well-known figure to Swedes who experienced the Second World War first-hand, were it not for the film The Last Sentence, Segerstedt might have remained unfamiliar to us here in the United States, as well as to European contemporaries.

The film The Last Sentence is based on the biography by Kenne Fant, who, in his former role as head of Svensk Filmindustri, gave Troell his first shot at directing films nearly fifty years ago. Troell collaborated with Klaus Rifbjerg in writing the screenplay which provides an even-handed treatment to Segerstedt as a righteous and perspicacious gentile. Segerstedt is not portrayed as saintly, but rather as a man in-tune with and directed by his passions — with equal zeal for his Jewish mistress/business partner as for his fight against fascism.

Troell is a true auteur, shooting and editing his features in addition to directing and writing them. The Emigrants (1971), with Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow, is perhaps Troell’s most well-known film in this country. Troell received Oscar nominations for Best Adapted Screenplay and Director for The Emigrants. Some of Troell’s additional film credits include The New Land (1972), the art house hit Everlasting Moments (2008), Zandy’s Bride, (1974, with Gene Hackman), and Hurricane (1979), which Dino De Laurentiis recruited Troell to direct when Roman Polanski fled the United States.

I had an opportunity to speak with the charming Jan Troell and his aspiring filmmaker daughter Johanna at the King George Hotel, San Francisco, where they were staying when Troell was being honored by the Mill Valley Film Festival in 2013, for the U.S premieres of The Last Sentence and Johanna’s documentary portrait of her father, A Close Scrutiny.

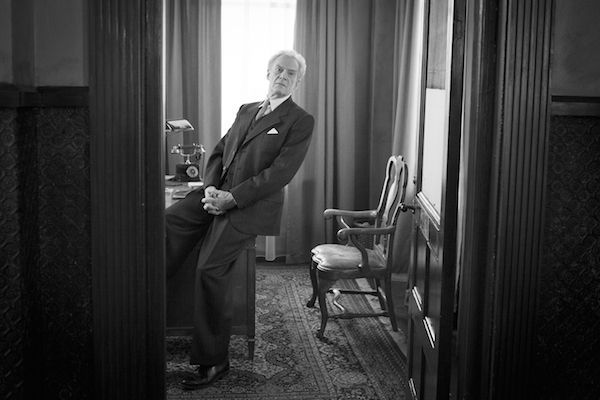

Photo courtesy of Music Box Films.

Sophia: What is so astonishing about Torgny Segerstedt is that from the start, he argued that Hitler was “an insult” and “a devourer of human beings.” What do you think it was that enabled Segerstedt to see so clearly what so many others were not able to see at all?

Jan: People in general knew that Hitler was anti-Semitic. Segerstedt wrote his first articles mentioning Hitler in the 1920’s. Very early on, he said that if Hitler came to power, it would mean war. I was a child at the time, and it was not until after the war ended that I learned about Segerstedt, but Segerstedt was a big hero to my father-in-law during the war.

Sophia: What do you remember of that time in history?

Jan: I was born in 1931, so I was eight years old, when the Second World War started. I remember, we had these little plastic soldiers (made in Germany), and we were playing war almost everyday — someone was always ‘the Allies,’ someone was ‘the Russians,’ and someone was ‘the Germans.’ On April 11, 1940, my family had to be evacuated. Denmark and Norway had just been occupied, and we expected the Germans to also take Sweden, so the authorities called for people to leave Malmö, the city where we were living. We moved four hundred kilometers north to a region with lots of forests. From the beginning, we were pro-Ally because my father was pro-Ally. I remember one playmate, a couple of years older than me, who was pro-German, but most of us were against Germany in our play. I did not really understand what was happening to the Jews in Germany until I read about it in 1945.

Sophia: What specifically in the Segerstedt biography captured your attention?

Jan: I am a little bit ashamed to admit, it was the women. The big story, the political story, was common knowledge. No, that’s not right, not among young people in Sweden, they didn’t know about Segerstedt. So the political story was, of course, interesting and important. But I was more curious about what kind of person Segerstedt was behind that image. As Segerstedt himself has written, “No man can withstand close scrutiny.” Segerstedt wrote critically about writers who use their work to diminish or scandalize others. When I read that, I thought, ‘What am I doing now, with this biopic? Is this right?’ Then on the following page, Segerstedt notes, “If someone wants to use the more scandalous sides of a person for purposes of writing, that’s O.K. for me, because that’s interesting.”

Photo courtesy of Music Box Films.

Sophia: I have never seen a film in which a husband gives permission to his wife’s lover to proceed —

Jan: That was unusual, I think. It’s particularly strange because when Segerstedt was a child, his own father had fallen in love with a mistress, and they openly publicized their relationship to the world, with the consequence that Segerstedt’s mother probably killed herself with morphine – just like Segerstedt’s mistress Maja Forssman does later. So history repeats itself. I thought, this aspect of Segerstedt is not so well-known to people. He had so much been put on a pedestal for so many people before. It’s not so interesting to show someone who is just a saint – because no one is a saint.

Sophia: There is a scene in The Last Sentence where Marcus Wallenberg, of the prominent Wallenberg Family, mentions that he has been approached by a German friend to encourage a big Swedish paper to write about the harassment of Jews in Germany. Marcus comments that “There are excellent Jews in Sweden, but that is not the case in Germany. If the Jews were exterminated, the country would lose good will. No foreign debtors would have their debts repaid.”

Jan: This is exactly what Marcus Wallenberg said in a letter to Segerstedt in 1932, before Hitler came to power. I just almost couldn’t believe that when I read it. It seems like it is invented for effect, but we’ve used the exact wording from the letter. Wallenberg’s use of the word “exterminated” is so eerie. Marcus Wallenberg was not an anti-Semite, but that was his exact wording. Germany was forced to repay a large debt after the First World War, as punishment. If Germany earned a bad reputation for pursuing the Jews, Germany either could not or would not be able to repay its debtors. So it’s a practical reason that Wallenberg cites [for defending the Jews] — which is such an outrageous thing to say, and also historically true.

Sophia: Johanna, what was your role on the film shoot?

Johanna: I came along to help my father carry his bags during the first week of the shoot because he had back problems. I was supposed to be there for three days, just to help him get settled, then I wound up staying for almost four months for the entire duration of the shoot. I could finally play a role that no one else could. I could be someone he could bounce ideas off without any hierarchy or prestige, without worry. We would just watch Fellini films all night long, eat chocolates, and bounce ideas around. During the shoot, I could remind him of certain things that we talked about the night before and contribute some ideas. It was just a very natural cooperation. If someone had asked if I had wanted to take on the responsibility of assisting my father for the entire shoot, I never would have accepted. Because it happened so organically, there was no way out. I learned a lot from it, and I also felt an obligation to help him.

Sophia: What did you learn?

Johanna: I aspire to be a filmmaker myself, and I am just starting out. Like my father, I want to learn by doing. If I know too much, I might lose the intuition, which is the most important tool, I think, for a filmmaker in my understanding. So being around my father, was great schooling, obviously. I also played the part of Segerstedt’s daughter in the film, Ingrid with the glasses. It’s a small role, but still, I wanted to do her justice because she was a real person, quite well-known in Sweden. I also shot the behind the scenes film. That was supposed to be my main priority, but, obviously, it became my third priority.

Sophia: At Mill Valley Film Festival, you are teaching a master-class in filmmaking, Jan. What do you hope to impart to the aspiring filmmakers?

Jan: To be curious, of course. To start shooting! To start doing — because you’ve got the instruments today so cheaply. Everyone today, with a telephone, can make a feature film — it has been done! Then, to watch other filmmakers and every kind of film. And to get a life, so you have something to express. Experiences in life — I wish I had many more experiences to build films on. I had a very protected childhood, just as Johanna has had. Thankfully, Johanna, you have been bullied in school, so you have something that protects you from over-protection!

Johanna: From arrogance, you mean? [Laughs.] No, but you are always talking about how you wanted to do more in your youth, because you went into teaching so quickly.

Jan: I wish I had lived a more adventurous life. All the things I didn’t do, I wish I had done.

Sophia: Earlier in your career, you directed Liv Ullmann.

Jan: During The Emigrants with Max von Sydow which was shot in 1969. I also worked with Liv Ullmann on Zandy’s Bride, with Gene Hackman. We asked her to play a part in this film, and she wanted to, but she was already committed to a role in the theatre. So she couldn’t do it.

Johanna: In interviews, Liv is always saying how she preferred my father as a director to Ingmar Bergman because the way he works with actors is so much more pleasant. On account of the fact that my father operates the camera himself, you never really know where or who he is filming, which means that everyone has to stay real the whole time, she remarks. It’s not your close-up, my close-up, his close-up. Everyone has to stay in the moment.

Sophia: You made two films in Hollywood, but then you turned your back on Hollywood. What was it about Hollywood –

Jan: I had no bad experiences while doing Zandy’s Bride. After that, Warner Brothers offered me a contract for ten additional films. That didn’t mean that you had to do ten films, but you were offered different scripts and so on. That didn’t suit me at all because I wanted to shoot my way, my subjects, and so on. So I didn’t accept that offer.

The Hurricane was a completely different experience for me. It was so big. It was the most important film that I made — because I met my future wife shooting it in Tahiti, Bora Bora.

Johanna: My mother.

Jan: Polanski was supposed to direct that film. He had already cast it, and then this thing happened with the police … There was a threat that he would have had to go to prison. So he ran away to Europe, more or less, had to. Dino De Laurentiis offered me the direction. The first couple of times, I said, “No,” because I wanted to do a completely different film (The Flight of the Eagle, which I made later, in Sweden). But there were problems getting my project financed, and finally my agent said “Come over and discuss it. They’ll pay for everything. Why not talk to Dino about it?” And so I did.

Sophia: What was your wife’s role on that film?

Jan: She was a journalist at the time. She came together with a journalist friend to do a story about the film.

Johanna: To interview you.

Jan: I refused any interviews, in the beginning.

Johanna: You were such a diva! She still hasn’t gotten the interview.

Jan: So it’s thanks to Polanski that we are here now.

Sophia: The score of the film is marvelous –

Jan: We have lots of music from the period. The main theme is Sibelius, Valse Triste, which I’ve known for many years. I didn’t think of it until I heard it on the radio when I was driving, but I felt immediately, this is what I would like. I wanted to use part of a quartet by Shostakovich that I had used when we were editing the film, but it proved to be too expensive. So we asked a Norwegian composer, Gaute Storaas, to write music with the same feeling. There is The March of the Finnish Cavalry, when the presses are running. One theme symbolized Segerstedt’s struggle, his fight against Hitler, and the other symbolized his relationships and his inner life.

Photo courtesy of Music Box Films.

Sophia: What is the significance of the title of the film, Dom över död man (The Last Sentence)?

Jan: The title is a quotation from the Icelandic saga, the Hávamál: “Your cattle will die, your friends will die, you will die too — but the one thing I know, that will never die, is the judgment of a dead man” — the reputation of a dead man, The Last Sentence. I like that title very much, because it refers to Hitler, Segerstedt also uses it in the film in reference to the King, and finally, Segerstedt uses it against himself, in judgment of his own life. “Dom över död man” means judgment or sentence over a dead man. “The Last Sentence” has a double meaning.

Sophia: We associate the Swedish national character with socialism and policies of social responsibility to one’s fellow man. How do you feel about the Swedish national character?

Jan: I tried to show my feelings about that in a three-hour documentary called Land of Dreams, (Sagolandet, 1988). Johanna played the leading role, from when she was born through her first three years, without even knowing it!

Johanna: My father made the film as a critical portrait of society, but both the right and the left embraced it as a representation of their own messages. I think that it is typically Swedish to both be very proud of being a Swede and your accomplishments, and then also to have feelings of inferiority. It’s a very strange balance.

Sophia: A sense of national inferiority is often a hallmark in countries with low GNP or poverty. In a First-World country like Sweden, what is the basis for such feelings?

Jan: During my life, I think feelings of inferiority have been connected to the War – that we stayed out of the War while our neighbors entered into the War. That feeling of guilt is still alive among Swedes. We feel a little bit ashamed. Our neighbors are still sometimes very critical of Swedish politics. But if you dig under the surface, no country has anything to be proud of in relation to how they behaved during the Second World War. It was save yourself, if you could. And if you couldn’t, and you had your back towards the wall, then you would fight. But to try to not fight …

“The Last Sentence,” starring: Jesper Christensen, Ulla Skoog, Pernilla August, Björn Granat. In Swedish with English subtitles.

Top Image: Torgny Segerstedt (Jesper Christensen) in Jan Troell’s “The Last Sentence.” Photo courtesy of Music Box Films.

“The Last Sentence” Official Website.