It’s summer in San Francisco, time to head to the park, demonstrate your hipness, and show off your tattoos. The de Young Museum’s big new exhibition for the season, “Ed Hardy: Deeper Than Skin,” does just that.

The sprawling show features more than 300 works, including early drawings from Hardy’s student days, cartoonish designs for tattoos, fine-art prints, paintings, decorated ceramics, and a 500-foot-long mural-like scroll, 2000 Dragons (top image), that displays several of his recurring visual themes. Some of the works are highly finished, others seem more like sketches or doodles.

The exhibition makes a case that Hardy transformed tattoos from an outsider craft to a mainstream art form, appealing not just to sailors, gangsters, and hippies, but to a broad cross-section of society. (About 30 percent of young Americans now sport a tattoo, according to a wall label.)

Hardy grew up in Southern California, showed a talent for drawing as a 10-year-old, studied printmaking at San Francisco Art Institute, and turned down a graduate fellowship at the Yale School of Art to became a professional tattoo artist in 1968. In 1973, he spent five months in Japan studying tattooing under the master Horihide.

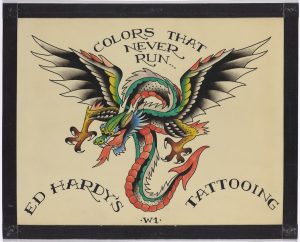

An undated illustration or poster, Colors That Never Run, advertises Hardy’s tattoo services with a fierce-looking flying dragon as its centerpiece. The creature sports a flame-like tongue, gorgeously extended wings, sharp claws, and a pointed red tail suitable for a devil.

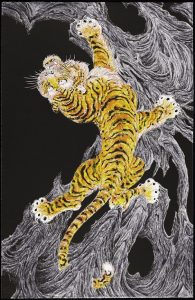

While much of Hardy’s early commercial tattoo work relied on traditional themes—skulls, flags, hearts, comic-book characters, voluptuous babes—the Asian influence is probably the most important. A lithograph like Climber of 2011 uses an odd overhead angle to depict a bright orange-and-black tiger climbing a monochromatic tree trunk. It seems essentially Japanese. It’s also a polished, mature work of art.

The creatures in 2000 Dragons are inspired by a 13th-century Chinese scroll. Yet the overall work, completed in roughly five-foot sections per day over more than 50 days in 2000, is maddeningly uneven. Some of the dragons are wonderfully rendered, both elegant and a bit scary, while others seem like rough drafts that didn’t really get Hardy’s full attention.

“Ed Hardy: Deeper Than Skin” runs through October 6 at the de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. An extensive catalog is published by the museum.

(Top image: Don Ed Hardy, Detail from 2000 Dragons, 2000, acrylic on Tyvek, collection of the artist, (c) Don Ed Hardy.)

Kabuki Bandits Show Off Their Tattoos

To explore the source of much tattoo art, head across town to the Asian Art Museum, where “Tattoos in Japanese Prints” is on view. It’s a handsome display of more than 60 prints on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, almost all from the 19th century, when tattoos became popular in Japanese art and culture.

The tattoo craze was fueled by the publication of a hugely successful set of prints in the late 1820s by Utagawa Kuniyoshi depicting the bandit-heroes of a folk tale known as the Water Margin. (The ancient tale, originally Chinese, was translated into Japanese in the 18th century.)

Kuniyoshi’s Du Xing, the Devil Faced, shows one of the bandits holding a gigantic bronze bell over his head as he crushes his enemy under a post. His back and upper arms are completely tattooed with a flamboyant blue design.

Many of the works in the exhibition depict kabuki actors playing various famous characters, as in an 1868 print by Toyohara Kunichika (above) that captures a moment of high drama among three tattoo-wearing sumo wrestlers. When a fight breaks out following a controversial match, the most powerful man—Washi no Chokichi, in the center of the three-panel print—steps in to separate the other two.

All three wrestlers sport elaborate tattoos featuring peonies, an eagle on a shoulder, and, on the left figure, a dragon and tiger that would look perfectly at home in an Ed Hardy print.

Beautiful Scrolls

Another show at the Asian Art Museum is not to be missed: “The Bold Brush of Au Ho-nien” presents 22 scroll paintings by a contemporary Chinese artist whose work is part of a traditional style from southern China known as the Lingnan School.

Now based in Taiwan, Au paints traditional subjects such as portraits, landscapes, and wildlife, complete with calligraphy, and occasionally updates the images with modern touches. One landscape, Scenery Around Taroko Gorge, shows a steep, mist-enshrouded, mountain that tumbles down to a road where tiny figures are walking. It looks like a timeless painting, though next to the two hikers is a small, bright-red automobile.

Some of Au’s most spectacular works in the show are the scenes of wildlife, including eagles, a prancing horse, a flutist riding a water buffalo, and—yes!—painted dragons coming to life before two artists.

Lion Companionship of 1963, in two scrolls, depicts a pair of truly regal lions perched on a high ledge. The male on the right surveys the landscape below; the female on the left appears to be sleeping. A close look at their paws shows how deftly Au captures the furry texture of their coats. It’s a spectacular painting.

“Tattoos in Japanese Prints” runs through August 18 at the Asian Art Museum, 200 Larkin Street, San Francisco. A catalog is published by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. “The Bold Brush of Au Ho-nien” runs through August 25, with a catalog published by the Asian Art Museum.